Women are legally entitled to abortion with few restrictions, but are often denied access to safe treatment because health providers refuse to perform the procedure for moral and religious reasons.

Abortion is as intensely emotive an issue in South Africa as it is elsewhere, especially in the United States (US), where it has long been contentious.

In recent times, the federal right to an abortion in the US following the landmark Roe v. Wade judgment has been reversed by several states. These have rejected the 1973 ruling that the Fourteenth Amendment of the US Constitution provided a fundamental ‘right to privacy’ that protects a pregnant woman’s liberty to choose whether or not to have an abortion.

Although Pope Francis has referred to abortion as akin to ‘hiring a hitman’, Catholic countries in Europe are witnessing demands for abortion rights. Some have birth rates that are lower than those in many non-Catholic countries.

In South Africa, as in the US, religious conservatism often correlates with an anti-abortion stance.

The United Nations’ World Health Organisation (WHO) argues that access to safe abortion is a key step in avoiding maternal deaths and injuries, and that restricted access to abortion services violates numerous human rights, including the right to life, health, privacy, and freedom from discrimination, torture and ill-treatment.

The transition to democracy in South Africa in 1994 led to the enactment of liberal abortion legislation. The Choice of Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1997 (CTOPA) repealed the Abortion and Sterilisation Act of 1975, which had stringent restrictions.

In 1998, the Christian Lawyers Association challenged the validity of the CTOPA. The basis of this challenge was that it violated the right to life in section 11 of the Bill of Rights. The then Transvaal Provincial Division of the High Court dismissed this argument, ruling that constitutional rights applied only to people who were born, not to foetuses.

In 2008, the CTOPA was further amended to enable trained nurses and midwives, as well as doctors, to perform abortions. It also provided for prosecution when abortions were done illegally.

Since the CTOPA was passed, the rate of abortion has increased across all provinces, and nationally by 222.4%. The two provinces with the largest increases are the North West and Limpopo, at 2 994% and 1 584% respectively. Abortion-related deaths and injuries have been reduced by an estimated 90% since the CTOPA came into force. However, legal abortion rates in recent years have begun to decline. Against an unofficial estimate of 260 000 abortions (legal and illegal) annually, only 85 298 legal abortions were recorded in 2016.

Despite South Africa’s liberal legislative stance on abortion, legal ambiguities in the legislation make it difficult to implement the CTOPA in the face of conscientious objection, which the CTOPA did not anticipate. While women in South Africa are legally entitled to abortion with few restrictions, they are often unable to access this service because the health personnel who are meant to perform abortions won’t do it – for moral and religious reasons.

This breaches the State’s obligation to safeguard women’s access to safe abortion care. There are three key barriers in policies and practice to safe abortion services: the failure of the law to regulate conscientious objection to abortion; inequalities in access to services for women from poor and marginalised communities; and the lack of access to information on sexual and reproductive rights, including how and where to access legal abortion services.

A 2014 study by Jane Harries, Diane Cooper, Anna Strebel and Christopher J Colvin showed that the main problem with abortions was conscientious objection on the part of health personnel. In most public sector facilities, the researchers recorded a general ignorance about whether healthcare providers were entitled to refuse to perform or assist in abortions. Medical staff seemed to have a poor understanding of their right to conscientious objection, and there are few guidelines. According to healthcare providers’ accounts in the study, it is often difficult to see how conscientious objection fits in the framework of CTOPA.

Another area where clarity is lacking relates to the refusal to perform abortions based on opposition to abortion in general. This is also not mentioned in the CTOPA. As it stands, the law leaves too much to the discretion of doctors and nurses. Clear guidelines on conscientious objection need to be provided, including the steps to be taken by a service provider wanting to register as a conscientious objector.

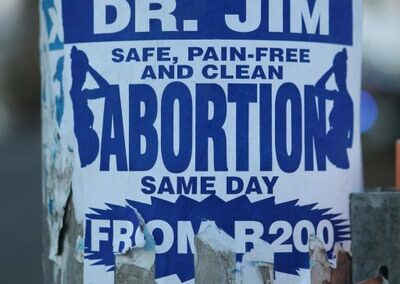

Data from the Department of Health shows that of the 505 health facilities designated to provide termination of pregnancy services, only 264 currently provide first and second trimester terminations. For women in rural areas in particular, this means travelling long distances to facilities and high transport costs. A list of the facilities providing safe and legal abortions is not readily available to the public, whereas a plethora of illegal abortionists are advertising in public spaces and online.

A 2013 study in Cape Town found that 45% of women did not receive the abortions they sought at a clinic. A related study in 2016 noted that 20% were turned away for advanced gestational age, 20% because the clinic did not have the staff to perform their abortions that day, and 5% because of the women’s inability to pay for their abortions.

Another key barrier to the implementation of CTOPA is knowledge of and access to abortion and antenatal care services. Antenatal care in early pregnancy is critical to protecting the health and lives of women. In South Africa, however, even though these services are free, many women do not attend clinics until late in their pregnancy. This has serious health implications, and can have fatal consequences in a country where roughly a third of pregnant women are living with HIV, and three quarters live in poverty.

Conscientious objection to abortion is widespread, with significant consequences for women who may be shamed or turned away from getting the operation, or forced to pay for something that is offered free elsewhere. Young women and teenagers in particular may face verbal and even physical abuse from nurses opposed to abortion.

As Amnesty International’s Deputy Director for Southern Africa Muleya Mwananyanda states: ‘A woman’s right to life, health and dignity must always take precedence over the right of a healthcare professional to exercise conscientious objection to performing an abortion. This is not the reality in South Africa. Regulation and clear policy guidelines are urgently required to correct the current vacuum.’

Katherine Brown is a politics Honours graduate from the University of Cape Town, currently interning at the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1. Terms & Conditions apply.