This article is the text of the speech given by Terence Corrigan, Project Manager at the IRR, to the Annual General Meeting of the IRR on 21 June 2019. It is quite a bit longer than our usual columns, but the insights and analyses of the real state of the nation are invaluable.

The Institute of Race Relations celebrates 90 years in existence this year. This is a major achievement for an organisation such as ours, but also an indicator of our continuing relevance. Let me begin by honouring one of our illustrious predecessors, Dr Ellen Hellman. A renowned anthropologist and long-time official at the Institute, she provided the definitive summation of the purpose and work of the Institute in in her 1979 book The South African Institute of Race Relations 1929-1979: A Short History: ‘The essence of the Institute’s work, trying to influence the minds of men, is by its very nature imponderable. Many believe that the effort has been meaningful… and derive comfort from the fact that proposals that appeared at first heretical when expounded on Institute platforms have become commonplace today’.

As it was then, so it is now, 40 years later.

Dr. Hellman was writing at a time in which South Africa was heading towards a crisis that only deep-seated political change would be able to head off. Perhaps it is a mark of a troubled politics that it manifests itself in a visible impact on the way one lives one’s private life, and the way one sees one’s personal future and that of one’s family. Not in the sense that it might make things a little better or a bit more difficult, but when it stands to severely constrain one’s prospects in life, or – and for most of us, this is probably even more important – those of one’s children. This was what awaited many South Africans in the years after which Dr. Hellmann published her book.

It is also what a great many South Africans experience today. We’re talking about ordinary people. People who work hard, save, want to pass the keys to a good life on to their children. For the most part, they love South Africa. Not in a bombastic way; but they cheer for our sports teams, enjoy beer round the braai, appreciate the rugged natural beauty (at least when they leave our cities) and the easy familiarity with which South Africans are able to get along with one another. If South Africa sometimes lacks the sophistication of France or the UK, the dynamism of the USA, the pleasant predictability of New Zealand or the tomorrow-belongs-to-me spirit of China, there are plenty of other things to recommend it.

There is also much to push people away. The confidence and relative prosperity of the early 2000s has dissipated. Insecurity is a constant feature of life. The people I’m talking about are people who worry about their bond payments, how they’ll fund their children’s education, and what they can contribute to their retirement funds. They are concerned about job security, or career prospects. They are apprehensive for their safety, and many can tell a story about how they or someone they know has fallen victim to the extraordinary levels of violence in the country. Some have chosen to seek futures elsewhere, others have given consideration to doing so. Most remain.

But more recently, what is confronting them is altogether darker. It is the sense that South Africa is not only facing extensive challenges, but that the country is purposefully driving towards it. Dr Hellman would probably recognise this.

It’s not a pretty picture.

And when an ordinary, decent, tax-paying worker in a white-collar or blue-collar profession – the sort of person this country needs – says that he sees the country as doomed, or that he feels that emigration is something he owes his children, we need to take that seriously.

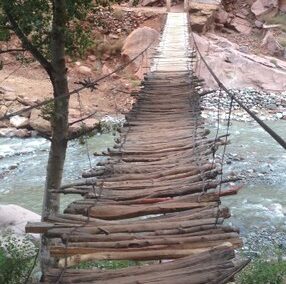

Facing the river

South Africa, we are told, is standing at a crossroads. I would like to alter the metaphor a little. Rather than a crossroads, it is standing precariously on a poorly maintained bridge over a torrential river. The bridge itself is rickety and planks within it may collapse. On the far side lies the destination we seek, beneath us, our destruction. We can give up and turn back. But the real trick will be navigating safely across it.

As we assemble here, there is no doubt that South Africa is facing some dire predicaments. As much as 55.5% of our population lives in poverty, at least as defined by income in 2015. Some 25.2% cannot afford enough food to supply minimum daily energy requirements. Some 17.5 million social grants are paid monthly. In this we have created what Mike Schussler has referred to as the largest welfare state in the world. As a palliative for poverty, this is commendable, but it also demonstrates probably the greatest failing of post-apartheid South Africa, the inability to generate employment.

Employment is not merely about earning an income, as important as that is. It’s about giving people pride and purpose, the sense that their efforts and their role in society mean something. It’s about conferring on adults the ability to be providers and role models for their children.

Yet the country’s terrible unemployment crisis – 27.6% of the labour force by the official definition or 38% by the expanded definition – grinds on. I recall, as I am sure some of you do, that the ANC came to power in 1994 promising ‘Jobs, jobs, jobs’. It was a hot-button issue from the outset, and was one of the first issues to merit that great South African treatment, the summit. President Mandela called for this – a Presidential Jobs Summit – back in 1998 to get all stakeholders together to come up with solutions. Last year, President Ramaphosa did the same. If that doesn’t tell you all you need to know, it certainly tells you a lot.

Indeed, our long-term progress on this has been very poor indeed.

One obvious reason for this – and a major problem in its own right – is the lack of dynamism in the economy at large. The GDP statistics that came out earlier this month gave a hint of the economy’s anaemia. With year-on-year growth at 0% and quarter-on-quarter registering a decline 3.2% – and this in the first quarter of the year, when activity tends to pick up – we’re seeing no sign of the sort of turnaround that South Africa is so desperate for.

With the global financial crisis, real GDP growth went negative in 2009, but went into positive territory again in 2010. The best we’ve made since then was 3.3% in 2011. Over the past few years, it has not even managed 2%. The reality of our current situation is that we are very likely heading into a recession.

Against this, the National Development Plan – this being the government’s standard, at least in theory – projects a growth rate of 5.4% as necessary to underwrite our development. Bear this in mind: the NDP was released in 2012, and envisioned South Africa in 2030. That means that we are fast approaching what should be the half-way point of its implementation. In terms of our growth rate, we haven’t even started to get there.

Over all of this, the odour of governance malfunction hangs rank and heavy. Perhaps because democratisation meant the displacement of a regime branded by a deep moral odiousness, expectations for accountable – and more than that – for ethical governance were high. Unfortunately, it’s been a hard lesson that democracies are not immune to governance pathologies. Corruption became a pronounced concern early on after the 1994 elections, but the scale of the damage that it could inflict has become glaringly apparent in the torrent of shameless behaviour that was on display over the past decade.

South Africans can demonstrate a heady combination of moralism and duplicity. Corruption evokes strong passions, declarations, summits, pledges, angry editorials and so on. But there is also a surprising tendency to skirt, to make excuses, to denounce conspiracies and draw fatuous if not odious comparisons. Somehow, it’s always possible to demand hard lines in the sand against corruption in general, but a soft landing for particular miscreants.

Perhaps even more serious, but often ignored for lack of a clear focus of moral outrage, is simply the ineffectiveness and incompetence of much of the state. This is about civil servants failing to do their jobs, even when this is not done out of malign intent or for personal gain. It’s what happens when the state takes responsibilities upon itself but refuses to engage the necessary skills. It’s what transpires when the state requires that people and organisations and businesses obtain all manner of official permissions to go about their business, but shows no hurry or special interest in processing them. Brian Pottinger, former editor of the Sunday Times, wrote a decade or so ago about the emergence of a sort of parallel state in South Africa. One part of this was the privatisation of services such as education, healthcare and security as the state’s offerings became suspect and ineffective. Another was the troupe of fixers and influencers that frequent government buildings, offering to ensure that frustrated people’s needs are met, for a fee of course. These, Pottinger says, have inveigled themselves into the state, essentially to perform the work that civil servants are supposed to perform, but are failing or refusing to do.

In essence, state failure – whether the outgrowth of corruption or of indifference or of incompetence – is rotting the planks over which we walk.

It’s a tumultuous mix of factors, a failure to address poverty sustainably, a malfunctioning economy, millions of people more or less permanently excluded from employment, a welfare system that is under increased pressure, and a state that is often leaning in some form of pre-collapse.

Add these things together, and that river surging below us is not only treacherous but toxic.

Thus, the response of the ruling party and the government has been not reflection and correction, not reform, but a doubling down on its current course. There seems an almost complete absence of any ability to recognise that a good part of what afflicts South Africa has its origins in the very choices the government has made these past three decades in response to the country’s challenges. The baleful state of our State-Owned Enterprises produces round after round of bail-outs, and a farcical roundabout of executives. The fiction remains that they are the muscles and sinews of the mighty developmental state, which is always under construction. The tangible problems – overstaffing, under-skilling, or whether they are even viable propositions any more – are ignored, or resolving them is deferred pretty much indefinitely. Privatisation is explicitly off the table. (Just in case you missed it, ANC Secretary General Ace Magashule said a few weeks ago that stopping the privatisation of SOEs was part of the ANC’s mandate. This seemed rather redundant, since it’s been rejected for well over a decade.)

Or consider the pronouncement of the ANC at its lekgotla towards the beginning of June: ‘The lekgotla agreed to reduce unemployment from 27% to 14% within the next five years while focusing on skilling and reskilling 3.4-million South Africans.’ It’s touching that the ruling party has made this determination. This will, we are told, be achieved by following the example of China, and by running a ‘three-shift economy’, one that never sleeps. This will be done in conditions radically different from China’s, and, presumably, by ignoring the central element of its success, the acceptance – however imperfect – of markets and capitalism. Rather, South Africa will continue its march towards ever greater state intrusion, the decapitation of property rights, the disincentives of empowerment legislation, policy uncertainty (if not simply bad policy). Accelerated manufacturing will be guaranteed in an environment of low demand and competitiveness undermined by red tape, labour legislation, infrastructural bottlenecks.

There is an element of fantasy about this. I recall a phrase in the opening credits of the TV science show Mythbusters, ‘I reject your reality and substitute my own’. Just so. This is what RW Johnson terms ‘magic thinking’. That by sheer force of will, a new reality can be brought into existence. Inevitably, this invites disappointment. And it steers us away from solutions.

It also breeds frustration. Onto this, there exists the constant temptation to graft divisive narratives. Business is on an investment strike. It’s unpatriotic. It’s white monopoly capital. Or to appeal to racial nationalist solidarity and incitement. All of this has its utility for unprincipled and unscrupulous politicians, but pushes South Africa ever more recklessly onto worn and unsafe footings. The country can ill afford the hostility and divisiveness engendered by lyrics that seem to call for the killing of people, by the crude stigmatisation of whole cultural, racial or professional groups, or the denial of some truly dreadful parts of our history.

Note here that what is all too often at play is not mere boorishness, not simply a case of bruised feelings in the course of robust debate. It’s often explicitly about stirring the base emotions of our politics.

Nothing encapsulates this more forcefully than the drive towards introducing a policy of Expropriation without Compensation (EWC). This is a policy at odds with any sense of what South Africa needs to boost its economic growth prospects towards levels that will start to make a serious dent in unemployment, or in sustainably improving the living standards of the millions of desperately poor in the country.

It is a chimera, a fraud concocted to play on historical resentments, to stoke racial animosity, to explain away the failings of land reform. Above all, it is geared towards extending the power of the state.

Its consequences, if carried to their logical conclusion, will be as deleterious as they are predictable. It carries a threat to South Africans individually and to the society of which they are a part. It represents a danger to their assets – indeed, a danger to something more profound, which is the ability to hold those assets as a right, rather than a conditional favour from the government – as well as a mortal blow against South Africa’s economic future. It prefigures, in other words, ruin for the individual and the household, and bleakness for future prospects.

How do we respond?

It is important to keep in mind that South Africa is no stranger to such circumstances. The Institute was established in 1929 to seek a solution to a challenge that most official opinion at that time hadn’t the conceptual breadth to even understand: how to create a society that recognised the reality of the interdependence of its multi-faceted population, which guaranteed the freedom of each individual, and which enabled each of them to rise to his or her full potential.

Or the 1950s and 1960s, where crises were visibly brewing, the official attitude was that they could be managed, they could be repressed. For most of its constituency, the prosperity of the era allowed the tumult below to be ignored as background noise.

Or the 1970s, the time in which Dr. Hellman wrote of the Institute’s mission, when the country faced an uprising, and the reaction of the state, encouraging the dangerous delusion in some quarters that repression (still) could be a long-term solution.

Or the late 1980s, when the country teetered on the edge of the abyss, where what was afoot was rendered opaque and distorted by a propaganda war whose goal was to turn reality into narrative. As our colleague Anthea Jeffery has repeatedly argued – most recently in her book ‘People’s War: New Light on the Struggle for South Africa’ – this war was darkly successful.

South Africa’s history provides a template for the present. For throughout most of our history, the IRR has struggled against power structures and (not infrequently) public opinion that was oriented against what we advocated. A non-racial society in the 1920s, for example.

The IRR was never in a position to aim for power directly, nor had it the resources to buy its way in. Nor was this what we have sought. Our strategy has always been one rooted in argument and persuasion, and in the vision we could offer. Dr Hellman’s words ring true here: it is our mandate and purpose to argue and explain to an often sceptical society why we find ourselves in trouble, and how we can extricate ourselves, so that what might have seemed like a heresy at one point, became merely outlandish later, innovative yesterday, and accepted wisdom today.

It is, in other words, a process of advocacy, difficult and uncertain though it often is. Making compelling arguments about what is at fault in the present, and how it might be altered for the common benefit in the future. In this we must counter contrary views, often those enjoying great influence in official and academic circles.

This we call the Battle of Ideas.

Fortunately, we are adept at this. The Battle of Ideas is one waged above all with information. We are proud to say that nothing – and let me repeat that, nothing – leaves the institute that is not factually and logically sound. Our annual Survey is the definitive compendium of information of the state of the country. It is equally respected by those who agree with us and by those who do not. I tip my hat to Thuthukani Ndebele and his excellent team for their work, year in and year out, on this.

It is matched by the monthly bulletins we release under the imprimatur of Fast Facts, by the information services we provide, and by the expertise of our talented staff

High quality information is critical to our endeavours, yet it is something that is ever more a point of contention. The deployment of slanted or fraudulent faux information is a regrettable fact of the present – what many will be familiar with as ‘fake news’.

To which we might add a distressing tendency to accept narratives not because they are consistent with the facts, but because they are ideologically attractive – and also because in a stressed society, people are inclined to trust hope rather than evidence.

Doing so is a risky undertaking, for it reproduces the delusions. Perhaps the Book of Hosea in the Bible puts it best, ‘My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge; because you have rejected knowledge.’

This we need to counteract; for our objective is not only to contest the ideas and perspectives of policy makers, business tycoons, intellectuals and editors, but also the population at large. The task of building the society is one that cannot and should not be left to elites, but one that must equally rely on the support and involvement of the community of free citizens. We understand that all of us need to be bridge-builders.

How does this unfold?

Over the past eighteen months, no issue has been quite as prominent, quite as divisive, and quite as damaging, as the issue of Expropriation without Compensation. Nominally, this is intended to accelerate land reform – although, strangely, research into the failings of land reform has not identified compensation requirements as a major shortcoming.

Permit me a small diversion into the Report of the High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and the Acceleration of Fundamental Change under former President Kgalema Motlanthe. It was scathing about much of what has transpired in respect of land reform since the transition to democracy. But it rejected the central justification behind EWC: this is that the constitutional requirement to pay compensation for property taken by the state has retarded the ability to undertake land reform. Said the Panel’s report: ‘Experts advise that the need to pay compensation has not been the most serious constraint on land reform in South Africa to date – other constraints, including increasing evidence of corruption by officials, the diversion of the land reform budget to elites, lack of political will, and lack of training and capacity, have proved more serious stumbling blocks to land reform.’

The first step in formulating a response is to understand what is taking place.

We at the IRR are mindful of the historical context – indeed, we monitored the abuses that land reform is intended to address in great detail – and we are in favour of a programme of land reform. It is the right thing to so, and, properly executed in its agrarian manifestation, it would have a beneficial (albeit limited) impact on South Africa’s socio-economic fortunes. But while we seek a land reform programme that builds ownership and enhances property rights, the proposals being put forward suggest something starkly different. In line with previous policy initiatives, it seeks to expand the discretion and latitude of the state.

For a population that is urbanising, for an economy in which skills and finance open up opportunities, land is a relatively minor consideration. Polling – ours and others’ – has repeatedly shown that. The deprivation of land, and the limits placed on black – and specifically African – landholding no doubt did much to create the poverty afflicting so much of our population, to foreclose the options available to escape it. But it is a profound misreading of the country’s contemporary economy to imagine that land reform, however well executed, constitutes a major path out of it.

We have long pointed to the outsized influence of ideology in the worldview of the ANC. Land – ‘the Land’, a sort of proper noun in the country’s political lexicon – is a prime ideological signifier. This is rooted in the history of the country, and so is understandable. It stirs political passions. But to be put forward as a solution to the country’s socio-economic malaise is ridiculous, if not dishonest. (Some months ago, I was interviewed by a prominent, and often insightful journalist. He challenged me that ‘surely’ – mark that word, it arises often! – the most logical way to address poverty and unemployment is to provide land to people so that they could make a living as peasant farmers. I’m not entirely sure whether or not he was playing Devil’s advocate, but it seemed incredibly bizarre if not condescending that a well-heeled urbanite would suggest this as a plan for the population at large. Especially since hundreds of thousands of people stream to our cities every year away from such an agrarian existence.)

This is not about ‘land’ in a rational economic sense. But it is about ‘the Land’ in a political sense. When President Ramaphosa refers to land dispossession as the ‘original sin’, or when – as happened during the debate on the constitutional amendment in February last year – land is a template for the venting of racial nationalist sentiments, this becomes quite clear.

Land is an evocative concept, and for none so much as our political elite. For the most part it’s safe to say that they are not much invested in gaining land for themselves. This is not about grabbing assets for personal enrichment (although in practice, it’s almost dead certain that this will happen), but about putting ideas into action. For the ANC, this is the National Democratic Revolution (NDR).

The National Democratic Revolution

The NDR is the master narrative. It posits an ongoing war of position. Make incremental moves here, push there. But keep the momentum up, and maintain the direction, even if tactical withdrawals may sometimes be warranted. As the ANC stated back in 2001, ‘the tensions that decisive application to this objective will generate will require dexterity in tact and firmness in principle.’

So what is the ultimate objective? At the risk of being circular, it is the National Democratic Society. This will be a harmonious community in which injustice has been expunged. A powerful, highly efficient state will ensure prosperity and discipline private business to fall in line with its developmental aspirations. At some level this will mean ‘resolving’ the tensions inherent in South Africa’s property relations.

From this flows, for example, the intense focus on demographic representivity in all things, the dogged rejection of privatisation, the willingness to pour billions into maintaining the suite of state-owned enterprises and a barely concealed hostility (when it is concealed at all) toward private business. From this also flows the idea that South Africa is ultimately on a pathway to socialism, and then to communism. The latter is explicitly espoused as the destination by the ANC’s communist and trade union allies. The ANC in itself may be more ambivalent, but in essence whatever disagreements may manifest themselves are of degree rather than principle.

Ultimately, there appears to be a general consensus on the need to abridge property rights. Property relations are, after all, at the ‘core of all social systems’. Whether the objective is a workers’ paradise with a statue of Marx on every corner, or a mighty East Asian-style developmental state, it will be necessary to expand the ability of the state to intervene and direct the economy. Moreover, the ANC’s reading of social relationships leads to the inevitable conclusion that the substantive dispossession of the former colonisers is an absolute imperative for achieving societal harmony – for resolving those tensions.

Perhaps no one captured this better than Ngoako Ramathlodi, who wrote in 2011 that the ANC had made ‘fatal concessions’ during that transition and that the result was ‘a constitution that reflects a compromise tilted heavily in favour of forces against change’.

Thus, it is profoundly misplaced to argue that what we are seeing is some sort of blundering populism. It represents deep-seated convictions. We at the Institute have tracked dozens of attempts over the past decade which have sought to degrade the protection of property on which ordinary people or private businesses could rely, while expanding the discretion of the state to intrude.

These started in earnest with vociferous attacks on the willing-buyer/willing-seller policy at the ANC conference in Polokwane. This prefigured the content of the draft Expropriation Bill of 2008. Later came the ending of the Proactive Land Acquisition Strategy in 2010, and then the Green Paper on Agriculture in 2011. The latter contained a range of suggestions, such as land ceilings and EWC. Then there was the 20% proposal in the National Development Plan of 2012, and the subsequent 50/50 proposal. The Land Restitution Amendment Act of 2014 opened the way for hundreds of thousands of new land claims while ignoring the critical need for a consummate budget to finance them. The Agri Land Bill tried to make the state custodian of farmland as the Green Paper had warned. The Regulation of Land Holdings Bill proposed capping farm sizes, confiscating what remained. Over the past eighteen months, the dominant push has been the proposed constitutional amendment and the Expropriation Bill, and regulations passed in terms of the Property Valuation Act.

Having understood what is underway, the second step is to counter it.

We have sounded the alarm about this, clearly and audibly. Too many commentators and influencers refuse to do so. Perhaps the scope and scale of the NDR make it seem just too audacious. Or perhaps it seems so thoroughly archaic that it’s difficult to take seriously. (One analyst whom I professionally admire and personally like, shot at me once that no one takes communism seriously these days, even those who say they do.) The consequence is that what is taking place is stripped of its context. Its motivations are misunderstood.

It’s our task to make sure that our analysis is presented both to elites, and to the public at large. Both have much to lose, even if the former have escape routes and bolt holes that the latter lack. If the full picture is not understood, any strategy to oppose or even to mitigate it will likely be misdirected.

We’ve seen this. ‘Surely’, we are told, this will be restrained by the sheer force of its own implausibility. ‘Surely’, the damage that it would inflict is understood. And ‘surely’ for that reason it won’t go ahead. Well, surely, those arguments would hold if the operative framework was economic, but surely not if it was ideological, and certainly not if that ideological framework verged on the messianic.

This informs both our messaging and reminds us of the challenges that we confront.

While the big picture message is important, communicating our perspectives requires us to segment our messages, so as strategically to explain the dynamics and risks at issue.

Thus, we have invested heavily in explaining the dangers of EWC to investment, to food security, to inflation and to employment. We have aggressively contested the idea that it is likely to produce anything other than catastrophe. The facts on this are quite clear, with the examples of Zimbabwe and Venezuela being illuminating case studies. It is notable how little effort is made by the advocates of this course of action to make a case for its economic benefits. In large measure, this part of our work is about making it clear that this is something that affects people personally.

What we have found, unfortunately, is that some outlets that should know better have attempted to downplay the damage that EWC will inflict – often doing precisely the opposite. Sometimes it is quite ridiculous. Earlier this year, the Financial Mail carried an extensive feature on EWC, with a cover declaring: ‘How land expropriation could work in SA… without destroying the economy’. Frankly, when one is suggesting the application of a policy in such a way that it does not ‘destroy the economy’, there is an admission that it is a very bad idea all round.

Aligned to this, we have shown that EWC is not something that will be contained within land or agriculture. This is how it has (erroneously) been understood in many quarters. But it builds on existing precedents and would create even more intrusive precedents for the future. Those who declare that ‘it doesn’t matter to me, I’m not a farmer’ need to understand that the EWC drive would place powers in the hands of the state – and probably more importantly, the confidence to repeat it – that would be applicable elsewhere. We’ve seen indications of this, in respect of copyright and the security industry. Indeed, just as many in the agricultural sector had to be brought around to understanding that EWC would not just be about abandoned stretches of desert in the Northern Cape and derelict buildings in Fordsburg, so bankers and industrialists and suburban real estate magnates need to understand that this is a policy that will be turned on their interests.

Similarly, we have pointed to the impact that degrading property rights will have on civil liberties. More than this: property rights are human rights, and are recognised as such in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The argument – sometimes made openly, sometimes subtly – that property rights are a dispensable bourgeois indulgence is a sinister one, and needs to be exposed as such. In a very real sense, property rights are an anchor for the others, since if the state can deprive people of their worldly goods and their means of sustenance, it wields a dreadful coercive power, one that is both explicit and implicit. (An aside: one factor that makes South African business so cautious in its dealings with the government is the extensive system of regulation and licencing in the economy, and the discretion accorded to officials and ministers in administering this. Best to remain on friendly terms, in the hope that the crocodile will eat you last. Or at least defer making you the meal until you’ve made plans for your wealth and your children’s futures, all the while reassuring your clients and society at large that you’ve full confidence in this country and its leadership.)

EWC has been fused with racial nationalist incitement and the stigmatisation of farmers. This predates the current drive. I recall well how these sentiments were on display at a conference put on by the SA Human Rights Commission in 1997. As one facilitator at the event – a prominent land reform activist – described farmers to me: ‘As far as I’m concerned, they have no human rights.’

This serves a purpose, since it provides another layer of justification for EWC – after all, if EWC is after ‘farms’, and ‘farmers’ are a particularly reprobate species, then who could be expected to sympathise with them, let alone come to their defence?

This is a wholly destructive way of thinking, tapping into some of our darkest impulses. It is also very often empirically incorrect. The tendency to label as a ‘farmer’ a white person accused of abuse is troubling and suggests that the stigmatisation campaign over the years has had some effect. We have been vigilant in challenging false claims.

One of these was the alleged force-feeding of sewage to a worker on a plot near Endicott in Springs in early 2018. The Star put the issue on the front page of its 31 January edition, using the words ‘farm’, ‘farmer’ and ‘farmworker’ 13 times – and claimed it was ‘the latest shocking incident in a spate of racist attacks endured by farmworkers at the hands of their employees’.

An IRR team went to the area, and was able to identify the premises within minutes – news reports had pretty much laid out the coordinates. A mere glance at the property made clear that this was no farm. Still, we spoke to a number of people in the vicinity who confirmed that there had been some deeply untoward behaviour there – and that the people involved were not farmers. In fact, the property was clearly signposted as a motor dealership.

Over the next few months we systematically challenged news reports, by contacting news outlets that misidentified the alleged perpetrators. Gradually, reports began to reflect more accurate terminology: ‘a family’ or ‘people’ rather than ‘farmers’; a ‘property’ rather than a ‘farm’.

None of this is to suggest that what took place there was not worthy of the strongest condemnation, but it is dishonest and unjustifiable to try and link farming or farmers to abuses conducted by a non-farmer on something other than a farm. Farmers are a large, heterogenous group, and it would be surprising if none were guilty of bad or criminal behaviour. That is true of all large groups – think lawyers, doctors, the clergy or police officers. I’ll refrain from discussing politicians.

We will use any platform to spread these ideas. Pretty much any platform, to any audience. From time to time I am attacked by people who are horrified that I met so-and-so, or a representative from this-or-that organisation. Well, with whom should we talk? Only to those who agree with us already? Personally, I am inspired by the accounts in the Book of Acts. How Paul, himself once a persecutor of the Church, became its foremost advocate, seeding it beyond its original home, speaking before crowds of pagans, and explaining his message in terms they could understand. I recall also the words of the Ethiopian eunuch who, when asked by the Deacon Philip whether he understood the scripture he was reading, answered, ‘How can I, unless someone explains it to me?’

Our strength has traditionally been in our writing, and the growth of electronic media in recent years has opened up channels that a generation ago would have been inconceivable. It would have been inconceivable to me when I first went to work for the Institute in 1997. To this end we have tried to produce at least one substantive written piece a day on the issue. On balance, we manage this.

A most exciting development in recent months has been the launch of our in-house video and podcast production facilities. We have been able to get our message out in new and innovative ways that are well suited to new audiences.

Aligned to this has been our new web-magazine, the Daily Friend. This has enabled us a regular, guaranteed outlet for our work. We are providing a stream of multi-faceted content to those who visit it (a particular focus being our Friends). Our views are presented, afresh, on any number of topics, predictably, every day.

We are also always available for engagement with the media. Constantly. Acknowledging the reach of a Business Day, a News24 or an IOL, an SAFM, or any number of community stations, not to mention foreign outlets (we’ve appeared in countries as diverse as Argentina, India, China and Australia), our team is ever ready to give comment and analysis, or to expand on what we may have already stated. Without the efforts of our intrepid media team – Michael Morris and Kelebogile Leepile – we’d never be able to do it.

At times, we’ve challenged media outlets on their depiction of issues. Perhaps nothing has been as enduring an issue as the constant misrepresentation of the official land audit (misrepresentations sometimes encouraged by the government), that white farmers own 72% of the landmass of the country. In reality, this proportion refers only to the 31% of land owned by private individuals and registered at the Deeds Office. At times, we have gone beyond writing replies, and challenged journalists and editors directly. At one point, we were given a spot on eNCA to argue our point. Unfortunately, I’m not sure the presenter really understood the response. But we push on!

Beyond that, we engage in targeted advocacy, face to face meetings with influencers and ‘interesteds’. Over the past eighteen months, we have stood before audiences in boardrooms armed with sophisticated Powerpoint presentations. We have sat in lounges and coffee shops engaging in free-wheeling discussions with sceptical journalists and commentators. We have been visited by embassies, industry representatives and think tanks. We have interacted with government officials, with political parties from South Africa and abroad. Every one of these represents an opportunity to help build pressure and to change the dynamics, and every one is eagerly seized.

Note, too, that we have traversed South Africa’s politics and the EWC issue with our own firmness of principle. That we have spoken against the ANC’s plans to seize property, and that we have sought to mobilise pushback, does not imply that we endorse or stand by those whose views ignore or downplay the genuine context out of which this arises. To do so would be to betray our own heritage. Thus, when Afriforum produced a documentary on the country’s land politics, we took strong exception to a few moments which glossed over, even misrepresented, the realities of forced removals. Afriforum has done the country a service by its opposition to EWC, and we wish it well on this. But to deal with what was so tragic and abusive as forced removals in any way other than its full unvarnished truth is to use broken planks to repair our bridge. It risks harming the cause, and dishonours our society’s history.

Finally, we have engaged over the past year in a process of recruiting what we term Friends. Unlike our clients and subscribers, they are not buying specific services. Unlike our members, they are not people with long-standing and finely-honed ideological commitments. They are ordinary people – the sort I described up front. They are people who worry about their future, and understand that they need to take up the cudgels to ensure that they and their families have one. For a small monthly donation, they have the assurance that they are sponsoring our work. Not merely on their behalf, but as our partners in this great endeavour. They have the knowledge that they are not forlorn and frightened voices drifting in the river, but part of a determined force of moderate South Africans who are setting to work. Indeed, they are the people whom we are referring to in our appeal to Unite the Middle. They, as much as any of us, are true bridge builders.

What comes next?

Fighting the Battle of Ideas is a long term endeavour. It is, for those who may appreciate the irony, a ‘Long Game’.

The ANC’s revolutionary theory posits that it can advance until it faces a resolute challenge. At that point a tactical retreat may be undertaken; once opposition dissipates, the advance can recommence. We understand this, and our work reflects it.

So far, we have done well in surging volumes of material into the public domain. In 2018, we produced some 858 opinion pieces, letters and so on. We gave 1 302 interviews. Adding this up to everything else we achieved 5 978 media hits, or 16.3 mentions a day. On EWC specifically, we put out 439 opinion pieces and letters, granted 246 interviews, were cited 610 times, issued 38 press releases and several hundred social media posts. In total, our work on this garnered 2 308 hits over the course of the year, or 6.3 mentions a day.

We believe there is good reason to believe that we have mounted an effective opposition. In private, officials have indicated that our work has hurt the EWC drive. And we have seen how the confident declaration of the intent to seize property (as Ramaphosa said in May last year, ‘we are going to take land and we are going to take it without compensation’) has given way to the blander formulation of ‘land reform’.

We have not let up. A great danger is complacency, to believe that a pullback on the part of the ANC and the government means major progress.

Complacency has, unfortunately, been the twin of Ramaphoria. The sense that the president is personally opposed to EWC, and that he will ultimately manage the process into some sort of symbolism (but nothing substantial), and that concerns are overblown, are very real. We have frequently been attacked as ‘alarmist’. We accept this – if it is ‘alarmist’ to raise an alarm when something alarming is afoot.

Ironically, it has taken the lead-up to the election, and the election itself, to shake this view. Now that the president has his mandate (which he would supposedly have needed in order to execute his alleged plan to neuter EWC), there has been as good as no evidence that he is changing tack. If anything, his cabinet reflected continuity rather than change – it didn’t even represent a significant reduction in size. ‘You might just have been right after all’, one executive said to us.

We believe we have been correct, both in our analysis and in our response. And we further understand that we are facing tough and resourceful opponents, who are striving for a goal in which they are deeply invested. This will not be resolved quickly or easily.

Fortunately, we know that our opponents understand our own mettle and our own commitment. We will push as hard as is needed, and if we are not able to stop this grave threat, we will be able to stand tall and say that we did not shirk our responsibilities as citizens, nor did we dishonour the venerable name of the Institute.

More than anything, we stand in an honourable tradition. It is one that informs, infuses and inspires our work day by day. It is the liberal spirit. I like to recall an anecdote in describing that. One radio host, evidently thinking he’d reached a gotcha! moment during an interview about EWC, asked rhetorically what our ‘agenda’ was. This is easy to answer. Our agenda is clearly stated on our website, and written on the walls of our offices: ‘We stand for classic liberalism – an effective way to defeat poverty and tyranny through a system of limited government, a market economy, private enterprise, freedom of speech, individual liberty, property rights and the rule of law’. Our agenda is to stop moves, such as EWC, which threaten it.

This is not merely a matter of politics or governance, but a standard of ethical and social behaviour, a striving for something better for all of us collectively and for each of us individually. I invoke Alan Paton’s words in 1953: ‘By liberalism I don’t mean the creed of any party or any century. I mean a generosity of spirit, a tolerance of others, an attempt to comprehend otherness, a commitment to the rule of law, a high ideal of the worth and dignity of man, a repugnance of authoritarianism and a love of freedom.’

It is an honour to carry some small responsibility for advancing this tradition. It is no easy task to work to ‘influence the minds of men’. Yet in doing so we seek to pour a balming oil on the roaring tides of our society, and to nail fast planks that will build the bridge to cross over into a better tomorrow.