Complacency is not an option – the seriousness of the threat posed by expropriation without compensation (EWC) must be faced squarely.

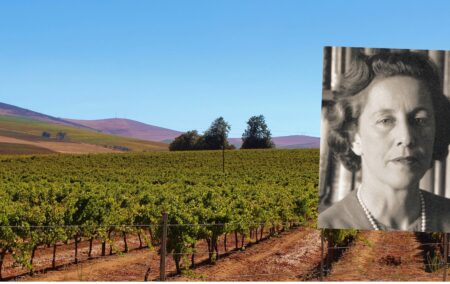

The Institute of Race Relations has always been proud to live out the injunction of one of its former presidents, Helen Suzman: ‘go and see for yourself.’ It’s intrinsic to the work we do. It helps us understand both the country’s realities, and the perceptions of them. It is a fascinating, intriguing and at times frightening experience. In moments such as the present, it is also very important.

Quite understandably, we hear all too often that people are concerned about their futures. So it was surprising the other day to speak to a farmer whose outlook verged on the sanguine, at least on one issue: ‘Things seem to have calmed down on expropriation without compensation.’

EWC – the drive by the State to empower itself to seize assets without paying for them – is arguably the severest threat to the country’s future to have presented itself since 1994.

And nowhere is this more immediate than in respect of the country’s farming community. Most of the ‘debate’ around this has been explicitly couched in land and agrarian terms. Farmers themselves have been the on-again-off-again target of abuse and stigmatisation as this has unfolded.

Nevertheless, our interlocutor could argue that EWC does not occupy the same profile that it did for most of 2018. And there is some truth to this. Whereas EWC was proudly trumpeted as a solution to the country’s land reform malaise – in messianic language, President Ramaphosa declared that it would turn the country into a Garden of Eden – it is now rather more sparingly deployed. Indeed, in public pronouncements, official talk is of ‘land reform’. In the State of the Nation Address, EWC was not mentioned.

Yet this is deceptive. ‘Go and see for yourself’. EWC remains proudly promoted by many within the ruling African National Congress (ANC). And even though the president neglected to mention EWC in his SONA, he was subsequently emphatic about it. ‘Parliament will have to deal with the Land Expropriation without Compensation Bill to achieve agrarian reform and spatial justice,’ he said in response to the Economic Freedom Fighters’ Julius Malema. Note that President Ramaphosa has chosen to describe pending legislation (either the Draft Expropriation Bill of 2019 or a prospective constitutional amendment) as the ‘Land Expropriation without Compensation Bill’. This is very revealing.

Perhaps equally revealing – although poorly understood – have been recent comments by Lindiwe Sisulu, Minister of Human Settlements, Water and Sanitation. She told Parliament: ‘With the new draft legislation for land expropriation in the pipeline, we will make sure that we are the first takers in the queue for expropriated land. In short, we will be the first expropriators as soon as legislation is passed.’

The initial target would be publicly owned land in Cape Town.

The minister’s remarks confirm that this measure is a firm intention of the government, that it is on the way, and is eagerly awaited as something to be used. Indeed, a cynic might say that she is confirming that it is a measure to be targeted at the ruling party’s opponents.

Her party colleague, ANC deputy secretary general Jessie Duarte – while defending the country’s ambassador to Denmark on her recent vulgar, racially charged outburst – separately confirmed a commitment to EWC, and made clear that privately owned assets, not least farmland, was firmly in its sights.

‘Go and see for yourself’. To imagine that the drive towards EWC has ‘calmed’ or that it will be a symbolic measure is to ignore a vast body of evidence, enunciated in clear language by the country’s political leadership from the president down.

It is a reckless idea that threatens harm. It has, in fact, already wrought great damage on South Africa’s economic fortunes, effectively gutting the prospects of a Ramaphoria windfall. And there is no evidence that it will do anything of value to advance land reform – the latter’s maladies lie elsewhere. Rather, it is a deeply ideological and political impulse, seeking ultimately State (or party) power over private interests.

‘Go and see for yourself’. For those millions of South Africans, of all colours and backgrounds – and particularly for farmers, established or emerging – EWC will not be a regressing concern, but a mounting danger. Complacency is not an option. The seriousness of the threat posed by EWC must be forthrightly realised, and squarely faced. Doing so offers the opportunity for organising a robust civic response against this path to ruin, and in favour of alternatives that will lead to opportunity and prosperity.

Terence Corrigan is a project manager at the Institute of Race Relations.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.