Last week’s mini budget laid out in stark statistics the magnitude of South Africa’s accelerating economic crisis.

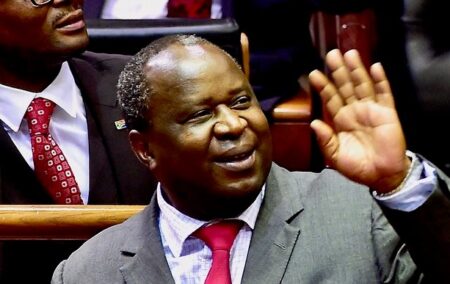

Finance minister Tito Mboweni expects a revenue shortfall of R250bn over the next three years, an increase in public debt from R3 trillion to R4.5 trillion, a 6.2% budget deficit on average, and a debt-to-GDP ratio of 71% in 2022, rising to 81% by 2027 if current trends continue.

In the face of these figures, as Mr Mboweni told his comrades in the African National Congress (ANC) and South African Communist Party (SACP), ‘there is no status quo option’, while ‘the consequences of not acting now will be grave’.

Which means it’s time to slaughter three sacred cows – and then develop pragmatic and effective policy alternatives instead.

First up for termination should be the pending expropriation without compensation (EWC) amendment to Section 25 of the Constitution. An EWC Bill to is due to be published on 10 December, for public comment over a six-week period timed largely to coincide with the December school holidays (when the country virtually shuts down). This truncated timetable is calculated to make a mockery of public consultation and is unconstitutional.

Equally disturbing is President Cyril Ramaphosa’s view that EWC will not only speed up land reform but also boost economic growth and increase food security. These assumptions make no sense when at least 70% of land reform projects have failed – and intensifying droughts pose major threats to farm production and livelihoods.

Even more important is the damage that EWC will do to property rights. As Piet Mouton, CEO of investment group PSG, told the Sunday Times last week: ‘The first time they take away someone’s land without compensation, it will be a phenomenal disaster’.

Any such taking will torpedo confidence, drive away investment, and hamstring all attempts to raise the growth rate. South Africa will lose its last investment grade rating (from Moody’s) and drop deeper into ‘junk’ status, making its economic crisis even more severe.

Next up for termination should be the National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill – especially now that the Treasury has confirmed in the mini-budget that the NHI proposal is ‘no longer affordable’ (if it ever was).

It makes no sense for the ANC to keep stressing the golden promise of NHI – free quality health services for all – while failing to admit that:

- NHI pilot projects costing more than R4bn brought no measurable improvement to public healthcare;

- many health professionals will emigrate, making waiting times for treatment even longer;

- a state monopoly over healthcare will be just as inefficient and corrupt as Eskom has become; and

- the major tax increases needed to finance the ineffective NHI will drive away many in the skilled middle class, making it harder to fund state services of every kind.

Additional ‘NHI’ taxes will also fall heavily on the poor, who will be badly affected by new payroll taxes (sure to limit jobs) and hefty VAT increases. Worse still, the ‘NHI’ revenues so collected are unlikely to be ring-fenced for healthcare and may instead be used to pay the public service wage bill and bail out bankrupt Eskom yet again.

Third in line is the 2018 mining charter, which must also go. As Mr Mouton says, ‘nothing is doing more to deter investors who are spoilt for choice in other countries’ than the charter’s demand that ‘they “give away” 30% of their investment, on top of all other taxes’.

The charter is supposed to help provide redress for apartheid injustices, but the disadvantaged gain nothing from driving mining investment away. In Mr Mouton’s words, ‘the people missing out on a better chance in life are local communities in mining areas’, for ‘if there’s no mine, there’s no jobs, no retail opportunities, no schools’.

This echoes what we in the IRR have long been saying. The escalating ownership requirements that have made the mining sector ‘uninvestable’ do nothing to empower the poor. Only a mining industry that is thriving and expanding can provide more opportunities for the disadvantaged to share in the gains from the country’s mineral wealth.

The mining charter should be scrapped and replaced by a new system of ‘economic empowerment for the disadvantaged’ or ‘EED’. This would include a new ‘EED’ scorecard that would recognise and reward mining companies for their vital contributions to investment, employment, innovation, tax revenues, and export earnings, among other things.

The EED system should also be structured so that it reaches down to the grassroots and provides the poor with tax-funded vouchers they can use to buy the schooling, healthcare, and housing of their choice. Schools, low-cost medical schemes, and a host of other entities would then have to compete for their custom – which would help to keep costs down and push quality up.

Little could be more effective than this voucher system in empowering the disadvantaged. Or in ensuring that tax revenues are better used, rather than being largely squandered on dysfunctional schools, clinics lacking medicines, and crumbling RDP houses.

Many other damaging sacred cows need in time to be slaughtered too. The BEE generic codes are just as hostile to investment as the mining charter and should also be replaced by EED. Rigid labour laws that deter job creation and put South Africa third last in the world for ‘co-operation in labour-employer relations’ need urgent reform. So too do the reams of red tape in which business is so often trussed, and the various laws already undermining property rights.

However, the three sacred cows identified here can all be jettisoned very easily. The EWC and NHI Bills need simply be abandoned. The mining charter, already under legal challenge from the Mineral Council South Africa, needs simply to be withdrawn.

These three simple steps would be real reforms of the kind Moody’s seeks if it is to avoid ‘junking’ South Africa next year. Taking them would see business confidence rise sharply from its current 20- or 30-year lows. Mr Ramaphosa’s sagging credibility would also receive a major and much-needed boost.

In the run-up to his investment conference this week, the president noted that ‘restoring investor confidence is the “lynchpin” of his economic reform agenda’. The withdrawal of these three measures would achieve precisely that.

Once these three measures have been taken off the table, sensible ways to achieve land reform, universal health coverage, and genuine empowerment can readily be found. Real reform of this kind would give people real hope that the economy is at last being helped out of the hole the ANC has dug for it. That would give all South Africans still more to celebrate than the country’s stunning Rugby World Cup win.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.