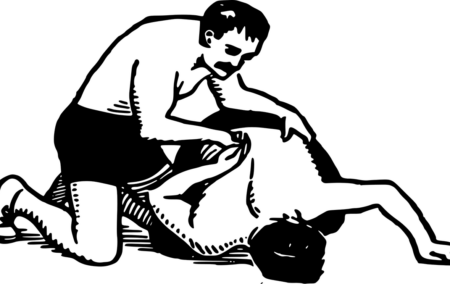

Just over two years ago, I began an article with a fragment from a 1973 Philip Larkin poem, a sketch from another time, as I put it then, of the oddly benign mechanics of wrestling bouts at a country fair, ‘not so much fights as long immobile strainings that end in unbalance’.

I thought South Africans might well recognise the dynamics of the African National Congress’s internal contest – this, just a month before the December 2017 Nasrec conference – in Larkin’s masterly image.

For a while, that seemed quite wrong.

As my senior colleague Frans Cronje wrote less than three months later, in February 2018, Nasrec was the moment when ‘we turned literally at the brink’, with Cyril Ramaphosa – having taken control of the ANC by a majority of just 179 votes at the elective conference – emerging ultimately as the national leader, too.

Optimism ran high, and not without good reason. The disastrous Zuma years were over. The new leader promised a decisive change in style and substance. Optimism welled among business leaders, and the rest of society, too. ‘Ramaphoria’ became a buzzword. We would stop short of the abyss after all.

Just over two years later, however – and two years is a long time in politics – Larkin’s picture of ‘long immobile strainings that end in unbalance’ seems a disturbingly apt reflection of how things stand in South Africa today.

In all this time, the IRR warned that rhetoric without action would be meaningless, and sentiment without substance would only sap confidence and deepen despair.

We were almost alone in our critical assessment of Ramaphosa’s maiden State of the Nation Address (SONA) in February 2018, pointing out that while he ‘spoke of “optimism” and “change”, sentiment and hope, of the hard reality that is the South African condition, he paid little heed’.

‘He spoke of a “new dawn”, but acknowledged none of the contemporary forces that brought about his election – the judiciary, the media, civil society, public advocacy and the opposition. Rather, he drew on the ANC’s history of old, and so, by omission, created the impression that the cause of the country’s decay and decline – the ANC – was, simultaneously, the cure.’

We were accused of being alarmist, and worse. Yet, as the new dawn passed, the sun rose only to cast an unforgiving light on the government’s failure to match its own declared intentions, chief among them, growth and jobs.

It is doubtful the optimists of early 2018 would have imagined this week’s Fin24 report that ‘one of SA’s biggest retailers, Massmart, has become the second SA company to announce possible store closures in 2020, a move that could affect up to 1 440 employees’, and this ‘just days after SA’s largest clothing retailer, Edcon, announced the closure of its Edgars store in Rosebank Mall, also citing underperformance’.

They might even have discounted the likelihood of what has turned out to be the government’s dogged pursuit of damaging policies despite every indication of their negative economic implications.

Key among these are expropriation without compensation, dressed up as means to reverse land dispossession but crafted in a way that risks only deepening economic vulnerability where it is most acute; National Health Insurance, presented as a healthcare panacea but guaranteed to reduce access to quality care for most South Africans; and the more vigorous application of race-based empowerment edicts in the face of evidence that they are hindering rather than helping the legions of disadvantaged people, the bulk of whom number among the millions of the unemployed.

As the country awaits Ramaphosa’s third SONA, it is salutary to revisit Cronje’s outline in late 2017 of the key factors influencing South Africa’s prospects.

These included:

- credible polling showing South Africans are more inclined to moderate middle-of-the-road opinions than economic and political populism and racial nationalism;

- popular confidence in the country being a function of the wellbeing of families and households (jobs, income and so on) rather than perceptions of political failings, corruption or headlines about state capture;

- high expectations founded on the genuine improvements in the lives of people post-1994 leading to a rising sense of grievance (and protest) because, following government and economic failures after 2008, these expectations have not been met, and

- the inescapable truth that such expectations cannot be met without structural reforms capable of triggering investment-led growth, and, among other things, without fixing the broken education system that presently condemns millions of poorly educated young South Africans to joblessness in an increasingly high-skills economy.

All remain pressingly relevant today. The only difference is that so much more is at stake; we cannot afford yet another round of fruitless wrestling.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1. Terms & Conditions Apply.