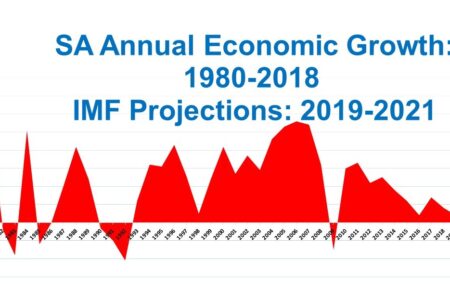

The Budget presented this afternoon is against a background of stagnant economic growth and declining per capita income. This stagnation and the dismal outlook make for the worst economic climate the ANC has faced in coming up with a budget.

South Africa is caught in a low-growth trap and per capita growth has been negative for the last 5 years. Yet, without reforms to restore business confidence, there is no chance of a rise in private investment to boost growth. SA’s predicament is as simple and yet as politically complicated as that.

Reforms to address the country’s disastrous government finances through cuts in civil service numbers, ending bailouts for Eskom and the other state-owned enterprises, and bringing in changes to allow faster and cheaper broadband, boosting tourism, and a host of other measures are seemingly barred either by bureaucratic inertia or deeply vested political interests.

There have been good years since 1994, but overall the country’s economic performance has been well below that of comparator emerging-market countries since 1994. SA per capita GDP growth has averaged 1.2 percent since 1994 compared to 2.8 percent for emerging-market comparator countries, and 5 percent for the top comparators.

Negative growth outlook

Economic growth has markedly slowed down from above three percent in 2011 and the consensus forecast is for around 0.4 percent last year. The outlook for the next two years is for negligible or negative growth, largely due to load-shedding and higher electricity tariffs, little private investment, and poor business conditions.

The hits to SA’s economy are largely domestic own goals. However, slowing global conditions due partly to the spread of the coronavirus interrupting global trade could add to the country’s economic misery.

Economic growth generates a virtuous circle in which companies and households enjoy rising incomes, allowing them to contribute to the savings pool to invest in opportunities that generate more growth and employment. With growth and rising incomes, government tax revenue rises, which ideally can be invested in projects, whether for infrastructure, education, healthcare, or poverty alleviation, which can help boost growth.

But South Africa is trapped in a vicious circle of low growth, high debt, falling government revenue, and low business confidence. The budget leaves little room for anything other than consolidation to lower spending and curbing the growth in debt.

Private investment is key

The IMF says the two fundamental reasons for low growth are less private investment and low productivity. The contribution of private investment to growth in SA was half that of the median Emerging Market group and 40 percent of the top growth performers from 1994 to 2018.

Total Factor Productivity, (which can be thought of as the magic sauce for growth that is a result of the effective adoption of technology and techniques in bringing together capital and labour,) has been declining in South Africa. According to the Fund, Total Factor Productivity growth in South Africa was above the median for Emerging Markets from 1994 to 2007, but then became negative and lower than the median in the ten years to 2018.

The IMF believes that this reflected the changing composition of investment – more investment from government and less investment from the private sector. There simply has not been much growth in private investment, and government investment has until recently grown. This indicates that much of public investment was wasteful and, in South Africa, does not make as large a contribution to growth as that from the private sector.

This substantially undermines any argument that the state can be as effective a contributor to growth as the private sector.

The most fundamental question about SA’s poor growth performance is, then, why is there little private investment?

South Africa’s returns on investment over the past five years have been below the level of other emerging markets. While companies with large market share in SA might face declining returns from investing locally, many SA corporates have invested abroad, which shows there is a low rate of return to private investment.

Doubt about investment gains

Attracting higher levels of private investment is a priority of President Cyril Ramaphosa, who has taken the initiative of holding annual investment conferences. He recently claimed success in generating commitments for R664 billion in new investment, half the target of R1.2 trillion.

Economist Mike Schussler says if these were all new commitments and would not have occurred and were in addition to the expected level, it would add about 6 percent to GDP a year. But forecasts simply don’t suggest that sort of increase.

Competitiveness indicators show that it is the macroeconomic environment, higher education and training, market efficiency and “institutions” – a term which covers everything from law and order to the effectiveness of government – that are the problems that stymie private investment.

Government has simply not addressed the big reasons for declining confidence. Electricity supply is unreliable, promised reforms are not implemented in a timely manner, and the ruling party is committed to changing the Constitution to allow Expropriation without Compensation (EWC).

The EWC concept strikes at the very heart of business confidence. The problem is that it subjects the security of property rights to the whim of government.

Property seizure worries

While the stated motivation behind EWC is the redistribution of agricultural land to ensure racially equitable ownership, it is far from clear what this process might unleash. It sets a precedent for the seizure of other assets that might not meet government ownership criteria. That scares the hell out of many owners of farms, businesses, and even householders. If the logic of land seizures is applied to other types of assets, it is unclear where the process might end. That’s not scaremongering, it is the way many private investors view the situation.

Then there are the secondary effects of EWC, none of them positive for investment and growth.

Most farms are highly geared businesses, as the owners tend to borrow to purchase and then take out seasonal loans to finance planting and other operations. What if there are massive defaults as a result of the inability of farm owners to service their debts due to land seizure? Done on a large scale, this would put the financial system at risk, and, done on a piecemeal basis, it is bound to result in banks cutting back on agricultural funding. Further, the process is bound to threaten jobs and result in food shortages and, therefore, higher inflation.

For a government committed to generating investment and growth, the commitment to EWC is a very poor decision. It is simply impossible to have EWC and high levels of private investment, growth, and a stable environment for a Budget that can aim at more than consolidation.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1. Terms & Conditions Apply.