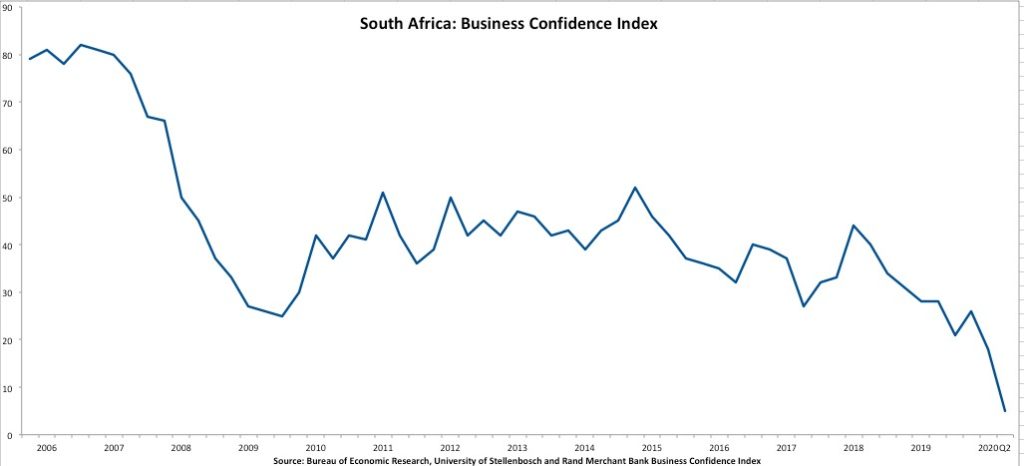

Business confidence, the magic ingredient that lies behind investment and economic growth, has all but collapsed in the country.

The Business Confidence Index (BCI) for the second quarter dropped 13 points to just five. That is the lowest level since the inception of the index in 1975. The BCI’s scale runs from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates a total lack of confidence, 50, neutrality, and 100, great confidence.

A level of five means 95 percent of those surveyed showed dissatisfaction with business conditions. All the component indices – retail, wholesale, manufacturing, building, and new vehicle motor trade – were down. The building industry was heavily down, with some firms facing cancellation of projects by clients.

Up until this collapse in confidence, the lowest recorded level was that of 12 index points in the third quarter of 1985. In the face of fast-spreading national protest and violence, then President PW Botha declared a State of Emergency, but had no credible reform plan.

The value of the index is that, over time, it has been a good indicator of future levels of investment and growth. The most recent reading shows that there is little chance of a strong recovery any time soon.

The index is ultimately an indication of how people in businesses will act based on the conditions they are experiencing. Questions in the survey are qualitative rather than quantitative, and include questions about sales, and intentions on investments and projects. About 1 800 people in senior positions with knowledge of their companies’ overall operations are surveyed each quarter.

The Bureau of Economic Research at the University of Stellenbosch does the work and Rand Merchant Bank is the sponsor. There is no doubt about its credibility as a reflection of business conditions and intentions.

The latest survey period covered the Level 4 lockdown, when economic activity was almost wholly suspended, and the announcement that we would enter into the less stringent lockdown Level 3. Confidence levels have fallen sharply across the world due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but in South Africa confidence has been low for the past decade and has been on a slide, bar a few blips, since Ramaphoria wore off in 2018.

Long-duration decline

In short, we came off a low level and went even lower. This collapse of confidence is not entirely lockdown- and Covid-19-related, as business confidence, bar some blips, has faced a long-duration decline. But our lockdown has been one of the world’s most severe, and for much of Level 4 was ham-fisted and overly restrictive on business.

In developed countries, large fiscal and monetary stimulus packages have probably prevented the sort of dramatic fall in confidence that South Africa has experienced. But these countries have also not experienced poor sentiment weighing down business confidence for a long time.

While the survey does not specifically ask questions about policy and politics, these clearly do feed through into sentiment, which in turns feeds through into confidence.

Policy certainty and a friendly business environment buoy sentiment, feed confidence, induce decisions to invest and set off a virtuous cycle. South Africa has lacked those for many years. The period immediately after 1994 was a period of immense optimism and with good policy, this optimism might well have been sustained.

There were early warnings of problems with state-owned enterprises (SOEs), Eskom lacking capacity, the labour laws not being investor-friendly, and a tightening of skill constraints. But there was, to an extent, trust in government and a sense that the problems could be resolved.

Miss the message

To blame the collapse of the BCI on the Covid-19 lockdown alone and to point to the worldwide phenomenon is to miss the message of why it was low and has now gone to almost rock bottom. Many of the country’s economists have for years ended their notes to clients with boilerplate sentences on the need for structural reforms.

In the past, South Africa has had sufficient fiscal space for rises in government spending to take the country out of a downswing and to allow confidence to improve. The country was taken out of the 2008 to 2010 business cycle downturn by President Jacob Zuma, who blew the budget surplus generated by President Thabo Mbeki on expanding the civil service and giving its members pay rises.

The adjustment budget in a week’s time will have no further room for fiscal stimulus. It will be about finding funding to support the extra R270 billion for the Covid-19 emergency package and finding R130 billion in cuts from the February budget.

There is also no monetary-policy scope to support a recovery. The Reserve Bank has taken unprecedented steps in a very short space of time to provide enough liquidity to try and ensure that permanent damage is not done to the economy. The Reserve Bank’s repurchase rate is now at 3.75 percent, a record low, and the central bank has blown its firepower.

‘We have got to accept that any response has got to be based on the resources we have or resources we can generate,’ Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago said in an interview with Radio 702 last week.

The only realistic alternative to boost business sentiment and confidence is big structural reforms. That is the only realistic durable option left.

Ramaphosa has missed good opportunities to come in with big structural reforms. There are no signs of imminent change.

Constraint on confidence

The lack of a reliable electricity supply is a constraint on confidence and growth. Eskom warned of pending power shortages in the late 1990s and, by 2007, chronic load-shedding had begun. Yet nothing has been done to resolve the problem.

The appointment of a SOE Council consisting of bright minds from the private sector and academia is not a sign of change, but might be an indication of hesitation. The parastatals have been in distress for years and the problems are well known. Delay on reforms undermines confidence, and exacts a toll on the economy both in terms of inefficiency and the need for endless bailouts.

The adage that ‘the ANC talks left, but walks right’ may well have been true for many years, but, with party resolutions and the rise in rhetoric, it has to be asked whether this will indefinitely remain the case. The threats to property rights from expropriation without compensation and the enforced use of pension funds to fund government projects through prescribed assets would further smash sentiment and what is left of confidence. Reassurances mean little to savers and business.

The problem is that once the process of expropriation begins, a precedent is created. While one knows where expropriation begins, there is no indication of where it might end.

Where does this place businesses that want to make decisions as going concerns?

It heightens risks, dampens confidence and means less investment, less business activity and fewer jobs. The latest drop in confidence has to be a serious warning about our direction of travel.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend