If there is a straightforward case to be made for reform based on freeing up markets and reducing the role of the state, it is the success of countries that have the greatest economic freedom compared to the failure of those with the greatest state control.

For the past twenty years, the Fraser Institute, a Canadian think-tank, has produced the annual Economic Freedom of the World Report to rate and rank countries on the extent to which they perform across five areas. The cornerstones of economic freedom are personal choice, voluntary exchange, freedom to enter markets and compete, security of the person, and privately-owned property.

Economically free individuals can make decisions on their own and do not have decisions imposed on them by threats of violence, theft, fraud, or the state.

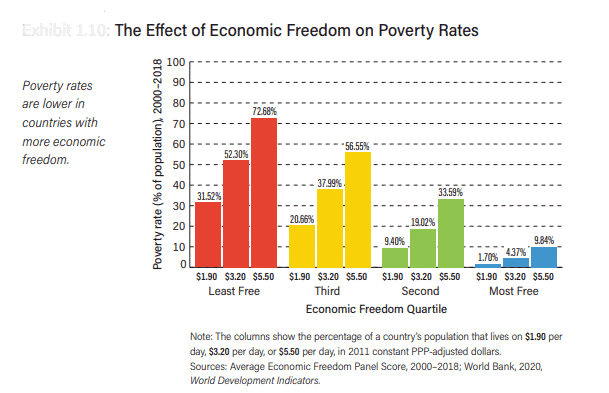

There is one overriding conclusion that emerges from the report, the latest edition of which was released earlier this month. Statistical evidence suggests that countries with improving and higher levels of economic freedom, on the whole, grow more rapidly and achieve higher levels of per-capita income, than highly regulated economies. Such countries also make greater inroads against poverty than countries dominated by government regulations and controls.

For South Africa, now in slot 90, the same as Tanzania, the glaring message from the report is that our economy is slipping in the rankings, while a number of other African countries are surging upwards. Mauritius now ranks seventh, Botswana 43rd, Uganda 50th, Rwanda 59th, Zambia 69th, and Nigeria 81st.

Hong Kong and Singapore have been in the top two spots since the inception of the rankings. This year New Zealand, Switzerland, the US, Australia, Mauritius, Georgia, Canada, and Ireland make up the rest of the top 10 in order. Mauritius is the only African country in the top group, but Botswana tops the second group. Clearly, consistency of sound policy earns good results.

As with the top performers, there is little change from year to year with the worst cases. Zimbabwe is at slot 155 and is followed by the Republic of Congo, Algeria, Iran, Angola, Libya, Sudan, and Venezuela.

The report covers 162 countries with 42 data points taken from freely available reports produced by such bodies as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and the World Economic Forum to produce a summary index. Extensive data is required for the report, which is based on data from 2018.

Top-ranked Hong Kong has a summary index of 8.94 compared to bottom-ranked Venezuela with a summary index of 3.34. South Africa has slipped down, from a summary index of 6.87 in 2000 to 6.73 in this year’s report.

The 42 data points are grouped into five areas: size of government, covering state spending and state owned enterprises; the legal system and property rights; sound money, covering the extent to which the central bank does its job of fighting inflation; freedom to trade internationally, covering the extent to which individuals can do business with outsiders; and finally the extent to which regulation may impose limits on the right to exchange, gain credit, hire or work for whom you wish.

The rankings are not contingent on wealth. Wealth helps in ensuring well-run institutions, but it can also bring about over-regulation. Higher-income countries do tend to fall within the first quartile of the rankings, but Mauritius, now an upper middle-income country, has been racing up the rankings. It is far above a ranking that would be based on GDP per capita alone. That places it above high-income countries like Canada, the UK, and Germany. Botswana, now a middle-income country, is in the same rank as Norway.

High-income countries tend to rank high in the Legal System and Property Rights area and Freedom to Trade Internationally, but their ratings are lower for Size of Government and Regulation, particularly in the area of Labour Markets. Some developing countries have a small fiscal size of government but rate low in other areas needed to ensure economic freedom, such as rule of law and property rights, sound money, trade openness, and sensible regulation.

Having a large welfare system and a legal structure to enforce property rights does not on its own make for greater economic freedom. In many high-income countries, over-regulation and protection can inhibit this.

The report is anything but a ranking of countries on the extent to which they meet extreme libertarian standards. All components of economic freedom are treated equally and there is no weighting given to the variables.

A small state in relation to the economy, on its own, does not ensure a high degree of economic freedom. An effective state is required to protect property rights, ensure law and order, fair competition, and enforce contracts and sound money. Countries require skills and institutions to achieve this, which in itself does require a measure of wealth.

Weakness in the rule of law and property rights drags down the ratings of many African and Middle Eastern countries, and several countries that were part of the Soviet bloc.

Although China has enjoyed phenomenally high growth rates, it only ranks at 124 due to a large state and its low rating in the area of its legal system and property rights. This perhaps raises the question about the durability of the Chinese growth model.

Will China need to improve its rating in these two areas to ensure high rates of growth well beyond its tremendous spurt since Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the 1970s?

The evidence from the reports suggests that there could well be limits on the authoritarian model for fast economic growth, precisely due to the large inhibiting role of the state. The report notes that “it will be surprising if the apparent increase in the insecurity of property rights and the weakening of the rule of law caused by the Chinese government intervention” in Hong Kong do not lower the territory’s rating.

What can we learn from all of this?

South Africa’s declining ranking reflects the drag of a large state and heavy-handed regulation. The only area of exceptional performance in the case of South Africa is the area of sound money, due to the role of the Reserve Bank in fighting inflation. The legal system and property rights are given a low rating due to the poor legal enforcement of contracts and the lack of reliability of the police. Freedom to trade internationally is burdened by the compliance cost of importing and exporting as well as exchange controls. And the rating on regulation is pulled downward by labour market regulations on hiring and firing as well as centralised collective bargaining. Businesses also face burdensome administrative requirements. Much of this has been known for a long time but would severely worsen if there South Africa adopts policies of expropriation without compensation and prescribed assets.

This report and the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Report only serve as sound handbooks for reform for those willing to accept the message.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend

Image by Nattanan Kanchanaprat from Pixabay