One of the weekend’s most-read stories on TimesLive was a warning that Cape Town’s coastal tourism is under threat from rising sea levels. It is farcical to be worrying about sea-level rise while government is taking a sledgehammer to the tourism industry.

The biggest threat to tourism, after the hard lockdown of earlier this year, is another lockdown. Whether it is to combat a second wave of Covid-19 infections, or a few years hence to combat an entirely new pandemic, government’s sledgehammer approach to fighting disease poses an existential crisis to tourism, among many other industries.

Amidst the destruction, the good folks at TimesLive want you to know that Cape Town’s beaches ‘are likely to disappear’.

‘The problem is so serious,’ the newspaper writes, ‘that businesses along the shoreline are urged to increase their insurance cover to protect themselves from an anticipated surge in damage caused by the rising sea levels and extreme weather. Cape Town tourist attractions which are at risk include Cape Point, the V&A Waterfront, Robben Island and a number of beaches in False Bay.’

If this sounds alarmist, it is. The report is based on a paper by three South African authors led by Kaitano Dube, a lecturer at Vaal University, and published in the Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism. (This column will increase its media mentions by 50%.)

The paper is largely reliant on anecdotal evidence of coastal erosion, and on what the authors describe as ‘a small sample of key informants who might have their own biases’. This seems a poor basis for reaching firm conclusions about future risk, but be that as it may.

Sea-level rise

As far as data goes, the paper reports sea-level rise of between 1.9mm/year and 2.1mm/year at Simon’s Town. At Granger Bay, it was what the authors described in scientific terms as ‘way higher’, namely 2.18mm/year.

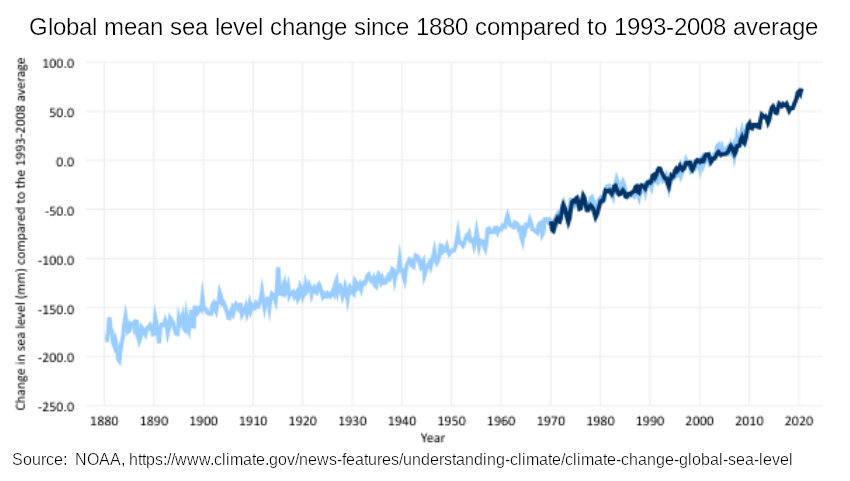

Global mean sea-level rise has been fairly steady since at least 1880:

There has been a recent acceleration (which may well be attributable to a change in measurement from tide gauges to satellite altimetry), but as you can see, that acceleration is hardly pronounced.

Although sea level will undoubtedly keep rising, perhaps even slightly faster than it has to date, nobody would say that the biggest story of the 20th century was that sea levels rose by 15cm. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts that sea levels will rise by at least a foot above 2000 levels by the year 2100.

That this will have an impact on coastal infrastructure is indisputable, but it’s not exactly a sudden and catastrophic impact. Defending against the sea is a well-understood problem for civil engineers. How many coastal structures are expected to last, unmodified, until 2100 in the first place?

Cape Town’s sea level is rising at a much lower rate than the current global average of 3.6mm/year. As per the chart in the paper, it works out to a grand total of 12.8cm between 1957 and 2017. That is hardly the end of the world.

If this total rise, or the present rate of rise, poses any problems to seaside infrastructure, especially during inclement weather, one might ponder the parable about the wise man who built his house upon the rock, and the foolish man who built it upon the sand. When the wind, rain and floods came, the wise man’s house survived, but the foolish man’s house did not.

This wisdom was not contained in a 21st century research paper, but in an ancient manuscript written way before anthropogenic global warming was a hot trend in academia.

The authors state that the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC) of 2019 ‘bemoans the impact of climate change on oceans and coastal communities’.

However, it also points out that human-induced non-climate-related developments are a far bigger threat than sea-level rise (SLR):

‘In low-lying coastal areas more broadly, human-induced changes can be rapid and modify coastlines over short periods of time, outpacing the effects of SLR (high confidence). Adaptation can be undertaken in the short- to medium-term by targeting local drivers of exposure and vulnerability, notwithstanding uncertainty about local SLR impacts in coming decades and beyond (high confidence).

‘As with coastal ecosystems, attribution of observed changes and associated risk to SLR remains challenging. Drivers and processes inhibiting attribution include demographic, resource and land-use changes and anthropogenic subsidence.’

Extreme weather

The paper also makes much of an alleged increase in extreme weather events, pointing to a report about 2019’s weather as evidence. In fact, there are very few detectable trends in extreme weather events.

On floods and droughts, the IPCC’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 ºC (SR15) of 2018 says:

‘Working Group II of AR5 [the 5th Assessment Report] concluded that socio-economic losses from flooding since the mid-20th century have increased mainly because of greater exposure and vulnerability (high confidence). There was low confidence due to limited evidence, however, that anthropogenic climate change has affected the frequency and magnitude of floods. WGII AR5 also concluded that there is no evidence that surface water and groundwater drought frequency has changed over the last few decades, although impacts of drought have increased mostly owing to increased water demand.’

In 2017, NASA detected a 24% decline in global fires between 1998 and 2015, and when asked whether this trend has since reversed, the author of a paper published by the Royal Society in October 2020 responded:

‘In the 20 years preceding our paper, an average of 71 deaths per year had been recorded in wildfire disasters. Since 2015, this has risen to 122. That noted, when considering the total area burned at the global level, we are still not seeing an overall increase, but rather a decline over the last decades.’

On storms, the NOAA analysed the available data, and found that any trend that could be attributed to climate change is ‘so small, relative to the variability in the series, that it is not significantly distinguishable from zero’.

The SR15 report does claim, albeit with only medium confidence, that the intensity of tropical cyclones across the world’s oceans has increased, although the overall number of tropical cyclones has remained the same or decreased. It does so without citing any papers more recent than 2014.

By contrast, the 2017 US National Climate Assessment says, with regard to global tropical cyclone activity, that ‘within the period of highest data quality (since around 1980), the globally observed changes in the environment would not necessarily support a detectable trend in tropical cyclone intensity’.

In 2019, a paper by members of the World Meteorological Organisation Task Team on Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change found ‘no detectable anthropogenic influence has been identified to date in observed [tropical cyclone] landfalling data’, and said ‘there is only low confidence in detection and attribution of any anthropogenic influence on historical TC intensity in any basin or globally’.

There is considerable uncertainty and conflicting opinions among scientists about whether a trend of stronger tropical storms is detectable in the data, and if so, whether that trend can be attributed to anthropogenic forcing.

Tourist spots

The list of affected locations in the article is taken straight from the Dube paper’s abstract. The first location on the list is Cape Point. This is what Cape Point looks like:

Of all the places that one might believe to be vulnerable to sea level rise, this isn’t it. Try Knysna, which for decades has salt water coming up the storm water drains and flooding the streets at spring high tides, especially when there’s a southerly wind blowing. Other than rusting cars whose drivers are silly enough not to take a short detour, this flooding does little or no damage.

The V&A Waterfront, too, doesn’t strike me as too vulnerable. The paper makes mention of sea erosion to some facilities at its far extremes, and contains a photo of a walkway that is being undermined, but that is exactly what one might expect when building right on the sea. The main development doesn’t appear to be under any threat at all, and remediation of the walkway seems to be a relatively simple matter.

A similar argument goes for beaches. Beach erosion and cliff retreat is a normal and expected process. It is unavoidable, no matter the mean sea level. Beaches are not permanent. They move constantly.

In Durban, for example, the erosion of its main beaches along the bight to the north of its harbour has been ongoing since the mid-19th century, as the harbour was developed and interrupted the littoral flow of sand from the south. The city has been pumping sand onto its tourist beaches since at least 1935.

That coastal tourism businesses must adapt to changing circumstances goes without saying. They operate in a highly dynamic environment, which can experience some of the harshest of nature’s conditions. Building too close to the sea has always been risky.

Yet that has not stopped high-value developments along the coast, nor has it stopped rich people from building seaside mansions. Insurance companies probably don’t need the speculation of a few academics to evaluate their risk due to changes in sea level or weather.

Advance, not retreat

In fact, the SROCC says: ‘Advance, which refers to the creation of new land by building into the sea (e.g., land reclamation), has a long history in most areas where there are dense coastal populations. Accommodation measures, such as early warning systems (EWS) for ESL events, are widespread. Retreat is observed but largely restricted to small communities or carried out for the purpose of creating new wetland habitat.’

That is not behaviour consistent with a fear of imminent inundation.

The authors of the Dube paper would like their largely speculative conclusions to motivate new tourism management approaches, including, as they say at the outset, increasing insurance cover, as well as ‘an urgent need for government to support climate-resilient mechanisms for the city to give it a fighting chance against climate change’. (Has there ever been an academic paper that recommended against lavish government spending?)

Dube, et al. have made a poor case, however. Any threat they have identified appears to be marginal, or will take place slowly over many decades, or both.

With the surviving companies in the tourism industry still reeling from the genuine catastrophe of coronavirus lockdowns, it seems unlikely that any of them, or their insurance companies, will be terribly worried by the supposed threat of a 15cm rise in sea levels over the next 50 years.

[Picture: Sawan Juggessur from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend