Wilfully incorrect, misleading and maliciously written falsehoods have been with us since the dawn of time.

In the distant past, the Bronze-Age Battle of Kadesh between the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II and the Hittite Empire in 1274 BC was long considered by historians a spectacular and overwhelming victory for the Egyptians over their Hittite foes.

This was based on numerous records of the battle found in Egypt that told of the glorious triumph and the heroic leadership of Ramesses II. While historians did not take the more outrageous claims seriously, it was generally taken as a moment of triumph for the Egyptians.

The truth was somewhat more complicated, and this was only discovered when, decades after modern historians had studied the battle, Hittite writings on it were discovered. These writings made clear that the Egyptian version as first discovered by earlier historians was a gross exaggeration of events and indeed may have been almost entirely propaganda, with historians today still debating if the Egyptians did in fact win the battle at all.

Ramesses II used his court scribes, among the few people in his kingdom at the time who could read and write, as well as his monument-building projects to craft a narrative of events which glorified him and his power while having little regard for the truth.

Thankfully, literacy is a bit more common in the year 2021 and so we no longer have to fear the state’s near monopoly on literacy. But just because we no longer get our news from official proclamations does not mean we are free of the problems of fake news and misinformation.

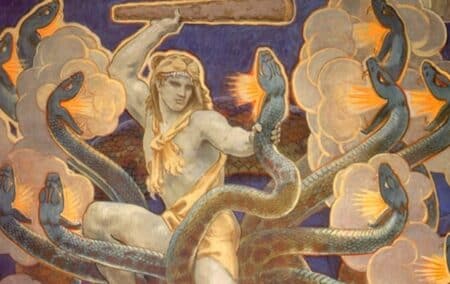

Indeed, as history has shown, fake news is much like a Hydra; every time a society seems to cut off the head of the fake news problem, advances in technology produce a new one.

Heretical

The early days of the printing press saw the publication in 1486 of a book called Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), which was roundly condemned by the Catholic church at the time as being a heretical work. It was written by an Austrian man outraged that a woman he had accused of witchcraft had been acquitted. Despite the official condemnation, the book was widely disseminated – using the new printing technologies – and became widely read across Europe, with some historians believing it sparked the witch-hunting craze of the 16th and 17th centuries.

In its earliest years, the printing industry came to be widely used by exiles, weirdos and heretics to spread their ideas at a time when this new technology had yet to come under the restraining influence of codes of conduct about what could or could not be published, or of centralised authorities capable of controlling the publishing of information.

Obviously, there were many upsides to this; new ideas changed the world and led to an explosion of innovation and culture. But this was also very disruptive, and it took decades to build up a publishing industry which maintained standards and which differentiated between fact and fiction.

Newspapers went through a similar process of formalisation, from the early days when the first newspapers were often filled with rumour-mongering, tall tales and falsehoods to the age of greater sobriety defined by the gold standard of three sources for every story (though, unfortunately, this seems to have devolved to three tweets per story in recent years).

With this historical background it should come as no surprise to us that the age of the internet and social media has opened a new front in the fake news conflict. In a report I co-authored with Terence Corrigan, we discuss some examples of social media-driven fake news, such as the genocide in Burma, and the social media furore over an incident involving some American high school students and a Native American protester.

Distorts reality

One of the findings of the report is that social media has allowed anyone to introduce almost anything into the mainstream of public discourse – this often distorts reality or propagates outright falsehoods. This in turn allows misinformation to spread at an incredible rate.

Anyone who follows Twitter regularly will have seen how breaking-news events can instantly have narratives formed around them to suit the political persuasions of those engaging in these fights. Disparate facts and isolated anecdotes of suspect authenticity are grasped from the swirling vortex of social media and formed into a simplified view of unfolding events. In such an environment, fake news can overwhelm any attempts to correct or rebut it. This can have dangerous results.

This problem, coupled with the fear among many mainstream journalists that Trump won in 2016 because of his use of social media, has sparked loud calls for regulation of social media companies. There have even been calls for legislation to be enacted to halt fake news. This is not theoretical at all. It is worth remembering that in South Africa, under Covid-19 state of disaster regulations, it is illegal to spread or create fake news.

Social media companies, under this pressure, have sometimes acted, usually clumsily or one-sidedly, to try to ban users of their platforms for spreading fake news. This usually serves to further entrench views, undermine debate and usually fails to stop the story gaining traction anyway. There are numerous examples of this, but a recent one was in April this year when Facebook banned its users from sharing a story about expensive house purchases by one of the co-founders of Black Lives Matter (BLM). This was unlikely to improve the image of its ‘fake news’ bans among critics of BLM.

Verifying information

The only real solution to the problem of fake news is for the public and society at large to develop institutions, practices and instincts that critically examine information from media, especially social media, even if it reinforces their prior views, and to call out people in their own social circles who perhaps unwittingly spread fake news.

Media institutions and public figures have a big role to play, here, by verifying information before spreading it, but ultimately any change in how we engage with new media will need to come from ordinary people. No government, company or NGO can solve this problem; it starts with each of us in our own media consumption.

If people do this, even allowing for inevitable failings and frailties, perhaps soon we shall have respite from the Hydra of fake news, at least until the next technology comes along.

[Image: Detail from the 1921 painting, Hercules, by John Singer Sargent]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend