The president is very proud of an agreement whereby rich countries will pay South Africa $8.5 billion (R131 billion) to ‘to support a just transition to a low carbon economy and a climate resilient society’. But what an awful deal it is.

At the latest climate orgy in Glasgow, a staggering 40,000 delegates gathered in luxurious hotels to sup on canapés, cocktails and caviar. Nobody expected it to achieve anything, and nobody was disappointed.

The hordes littered the city with glossy marketing brochures agonising over alarming prognostications and catastrophic model projections. It is a wonderful venue for young rebels with anxiety and a Messiah complex to get validation from boomer hippies for their hollow gestures to ‘save the world’.

Yet two weeks of talk shops, punctuated by drunken revelry and exorbitantly expensive meals, have produced nothing more than a few promises that will be broken, and would achieve very little even if they weren’t.

Most of the governments of the largest economies in the world were simply not prepared to sign anything at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change’s 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) that would amount to meaningful action.

Alarm

That alarms me less than it might alarm others. I have long been cynical about the catastrophism of the environmental movement. I find their exaggeration to be routine, their ideological agenda to be naked anti-capitalism, their motivation mercenary, and the underlying science to be far more cautious and uncertain.

Even if we accept that human carbon dioxide emission is the primary control knob of the climate, it is far from clear to me that dialling it down rapidly won’t be far more costly, in lost economic development, than getting rich enough to adapt to the changing climate.

If that knob does have to be turned down, however, it seems that those who contributed most to present-day high carbon dioxide levels ought to be doing the turning.

Instead, the US, Russia, Saudi Arabia, India, China, Germany – all the major powers – ensured that they conceded as little as possible. In the end, they cut a deal, but left COP26 president Alok Sharma on the verge of tears as he declared, unconvincingly: ‘We can now say with credibility that we have kept 1.5 degrees alive, but its pulse is weak.’

One and a half degrees Celsius higher than pre-industrial levels is the most extreme target for global temperatures by 2100, among the sort of people who believe we can control and direct the global climate.

Coins for a beggar

The great powers, staggering from whisky bar to cigar lounge, did toss some coins to an African beggar busking on the cold Glaswegian pavement. That beggar was Cyril Ramaphosa, who broke into a broad grin and mumbled his thanks for ‘a historic international partnership to support a just transition’.

The rich countries had always held out the promise of climate bribes to keep poor countries in line. The strategy is for the rich world to rest on their laurels, having achieved industrial development, while paying poor countries to stay poor and under-developed by switching to more expensive and less reliable sources of energy.

The rich world in 2009 promised to pay the poor world $100 billion per year in ‘climate finance’ by 2020. That ‘climate finance’ was supposed to get poor countries to reduce their carbon emissions and adapt to climate change, so rich countries could sit on their couches doing nothing.

In 2015, the developed countries reaffirmed the $100 billion per year promise, but by 2020, no cash had materialised. All the developing world got was a pandemic.

This year, they prepared a lovely report containing ‘a transparent and consultative Delivery Plan showing how and when the goal will be met’.

It’s your basic ‘the dog ate my homework’ excuse.

No wonder the president of the Maldives, the island nation that claims to be drowning but built five new runways, literally on their beaches to accommodate the tourist boom it was expecting pre-pandemic, was at COP26 whining that the rich countries weren’t living up to their promises.

We’re okay, Jack

As if developing countries like South Africa, which contributes a little over 1% to global carbon emissions, are the problem. Just six countries emit 60% of the world’s carbon dioxide: China, the United States, India, Russia, Japan, and Germany.

Forty-six countries – Qatar, Montenegro, Kuwait, Trinidad and Tobago, United Arab Emirates, Oman, Canada, Brunei, Luxembourg, Bahrain, Australia, Estonia, Gibraltar, the Falkland Islands, Saudi Arabia, United States, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Iceland, Taiwan, the Bahamas, Russia, the Czech Republic, Bermuda, Japan, the Netherlands, Germany, Finland, Malaysia, Singapore, New Caledonia, Austria, Belgium, Ireland, Norway, Libya, Iran, Israel, Poland, Bosnia and Herzegovina, China, Martinique, New Zealand, Bulgaria and Slovenia – all emit more carbon dioxide per capita than South Africa.

Yet we’re the problem.

France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union flipped a few pennies to Ramaphosa, supposedly to switch away from coal, in what the New York Times views as a test case to see ‘how [climate finance] would work in practice’.

Well, the joke’s on them. South Africa is already moving away from coal. We’ve shut down, broken or blown up a third of our coal-fired power stations. Since 2008, we’ve used less coal-fired electricity year on year, every year.

We don’t need their pitiful money to de-industrialise. We’re doing it on our own, in our Proudly South African way.

Our GDP is down the toilet. Poverty and unemployment are at all-time highs. This is exactly what happens in the absence of inexpensive, reliable energy. The pandemic was just a cherry on top of a long-term downward spiral that began when Eskom first turned the lights off in 2008.

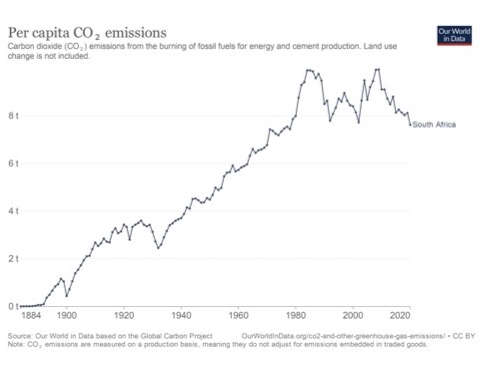

As a consequence, we’ve long ago cut our carbon dioxide emissions. Per capita emissions in 2020 were at levels last seen in 1978.

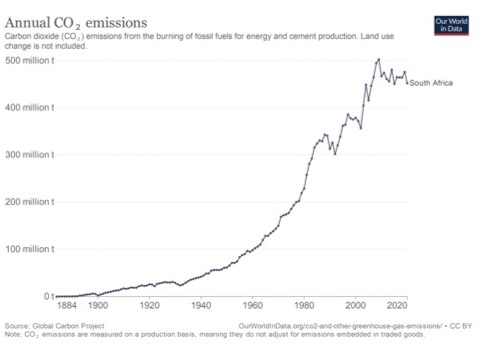

Total emissions have also been on the decline since their peak in 2009.

Yet we’re the problem.

I mean, the scientists don’t even know what emission levels really are. They guess. Their latest guess is that, instead of rising precipitously, as we’ve been told, global carbon emissions have actually been flat these last ten years.

Energiewende

That R131 billion donation, once it has been processed and skimmed, perhaps via Chancellor House, will neatly fit a debt hole at Eskom, though.

The donor countries want the money to be spent on solar and wind power, electric vehicles, and hydrogen, so the green tech millionaires will be lining up with their snouts in that trough.

Like South Africa can use electric vehicles when it can’t even keep the lights on!

It is reprehensible to try to force an ‘Energiewende’ on a country that sits on a pile of cheap coal and has been slashing its emissions like there’s no tomorrow.

This obsession with renewable energy is how South Australia got the most expensive electricity in Australia (plus a few major blackouts), and Denmark and Germany got the most expensive electricity in Europe.

And they have the benefit of flexible energy import-export markets, so they can deal with the surpluses and shortages that are characteristic of renewable energy. South Africa has no such import-export buffer.

Europe’s cheapest electricity is in Bulgaria, which, like South Africa, sits on a mountain of coal.

Sold down the river

The culprits in all this are not the sleazy fat cats who fob the beggar off with a few coins. The real scoundrel here is Cyril Ramaphosa, who is prepared to sell his own country down the river in his desperation to make up for the billions his party stole or mismanaged.

The future of African energy shouldn’t be the subject of bribes from the former colonial masters. Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe is not wrong when he says that Africa should resist attempts by developed countries to force them to abandon fossil fuels.

‘The sad reality of this situation is that there has been a preoccupation with Africa,’ he said in a recent speech. ‘Yet our Africa is the least polluter compared to the other continents. This is a sign of encirclement. Africa is being encircled by the rich and powerful. Our continent, collectively, and her individual countries, is made to bear the brunt of the heavy polluters. We are being pressured, even compelled, to move away from all forms of fossil fuels – including resources such as gas, which have been regarded as key resources for industrialisation.’

South Africa, and Africa in general, should remain free to use every form of energy at its disposal to boost development, support economic growth, and reduce poverty and unemployment.

That mix could include renewable energy, but only if it is commercially viable without rich-world bribes and subsidies. It must also include nuclear and gas. If South Africa chooses to phase out coal, it should do so on its own terms, without putting its economy under unnecessary pressure.

Frankly, the top priority in South Africa right now should be to get the coal fleet working properly again, to get the country’s industrialisation back on track. This country doesn’t have the luxury to indulge the renewable energy fantasies of the global north.

By accepting bribes from the developed world, we help them to assuage their own guilt, but we are demeaning ourselves and committing ourselves to a future of more expensive, less abundant energy.

One might have hoped that the era of colonial exploitation was over, yet here we are, saying, ‘Yes sir, as you wish, sir,’ in return for a few crumbs from the master’s table.

The views of the writer are not necessarily those of the Daily Friend or the IRR.