This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

11th January 1879 – The Anglo-Zulu War begins.

The Zulu empire was famously founded by Shaka Zulu at the beginning of the 19th century and quickly rose to prominence as one of the most powerful, if not the most powerful of the African kingdoms in Southern Africa. The traditional story of the rise of the Zulu claims that Shaka instituted a massive social and military revolution purely of his own genius. Shaka himself is famed as a legendary figure, the son of a chief rejected by his clan and denied his birth right he returned to defeat his father and become a mighty figure of legend.

Modern historians, however, are far more sceptical of this story, as little direct evidence of Shaka’s life remains. Most of the evidence is some Zulu oral history and praise songs and some accounts from much later in Shaka’s life, written by particularly unreliable European traders who may well have either confused details or exaggerated stories of Shaka so as to build their own fame.

What is generally agreed on is that Shaka left his home clan and sought refuge with the Mthethwa empire, one of the major powers of the region of modern-day Kwa-Zulu Natal. At the start of the 19th century. Shaka became a vassal of the Mthethwa and achieved experience and fame leading Mthethwa troops into battle against their enemies. When Shaka’s father, Senzangakhona, died, Shaka’s half-brother, the legitimate heir to the Zulu chieftaincy, assumed the position of chief. Shaka was given troops by the Mthethwa king, Dingiswayo, to allow him to go home and contest the Zulu throne, which he successfully did, killing his brother and assuming the leadership of the Zulu clan, at the time one of many smaller Nguni clans that dotted the region. At this time Shaka remained a vassal of the Mthethwa.

Shortly after Shaka’s rise to power over the Zulu, Dingiswayo was captured during an invasion of the Ndwandwe territory and beheaded. The Mthethwa empire disintegrated with Dingiswayo’s death and Shaka sought to avenge his overlord’s death. In the chaos of the collapse of the Mthethwa, Shaka led the Zulu to prominence, smashing the Ndwandwe and creating the Zulu empire. The conflict between the Ndwandwe, Zulu, and Mthethwa caused a wave of instability and violence across Southern Africa as the defeated clans fled the region into their neighbours’ lands, often raiding or conquering as they went, a period today known as the Mfecane the result of which was a reorganization of the political boundaries within Southern Africa.

The Ndwandwe would flee KZN and establish new Nguni-speaking empires in Mozambique and Malawi called the Gaza and waNgoni empires.

Shaka would rule the Zulu until his death in 1828 when his half-brothers, Dingane and Mhlangana murdered him and Dingane became king of the Zulu.

The rise of the Zulu to dominance over a significant chunk of Southern Africa is attributed to the genius of Shaka and his reforms of the Zulu army and society. Many historians believe that this telling is overstated and that Shaka did not invent his reforms entirely but rather accelerated changes already underway amongst the Nguni clans at the time. It’s also possible some of his military reforms were learned while serving in the Mthethwa army or from his enemies.

These reforms are most importantly, the adoption of a shorter stabbing spear, the iklwa, focusing his forces on more decisive and destructive engagements and a much more militarised version of the traditional Bantu age group system which organized men into disciplined regiments based around military Kraals. This regiments system gave the Zulu king enormous power over his troops, as he controlled their social status and right to marry and allowed the Zulu kingdom to mobilize a significant pool of manpower for war without the need for an advanced bureaucracy.

With Shaka’s death, his kingdom endured but was plagued by internal conflicts. The kingdom also became increasingly involved with the British Empire and the Boer Republics who were both expanding their control over Southern Africa at this time.

Clashes with the Boers, most famously at the Battle of Blood River, and trade with the British initially led to much friendlier relations with the British as the Zulu sought their protection against the Boers. Due to the decentralized nature of the Zulu state and the differences in culture and law between the British and the Zulu occasionally disputes arose along their borders.

In 1873 Cetshwayo became King of the Zulu (although he had been the true power amongst the Zulu for many years after defeating his brother in battle). His ascension as king was supported by the British and he was even crowned in a ceremony by the British official Theophilus Shepstone. During this period Cetshwayo sought to modernise his army by acquiring firearms through trade and to protect Zulu independence by playing the British and Boers off each other.

Unfortunately for Cetshwayo, in 1874 Lord Carnarvon, Secretary of State for the Colonies, decided to repeat his success in creating a confederation in Canada that centralized control of the region into one entity and reduced the governance costs of the colonies there.

He aimed to do the same thing in South Africa uniting the British colonies of Natal, the Cape, the African Kingdoms of the Sotho, Swazi and Zulu, with the Boer Republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free state in a confederation. The principal obstacles to this were the military power of the Transvaal and the Zulu Empire. In 1877 he appointed Sir Bartle Frere to the position of High Commissioner for Southern Africa to carry out his confederation plans for South Africa.

In 1877 the Transvaal was annexed by the British Empire (an annexation that would end in the First Anglo-Boer war). Theophilus Shepstone, the British Secretary for Native Affairs, in Natal convinced Frere that with the Transvaal annexed the great remaining threat to confederation and the Natal colony was Zulu military power, and that a war would be needed to defeat the Zulu and absorb them into the Empire.

The British government in London was not keen on a war with the Zulu, having had good relations with the Zulu, and Lord Carnarvon was replaced in November of 1878. However, Frere was already well on his way to enacting the confederation plan and saw no reason to stop despite London’s fear’s they were overstretched.

At the same time Cetshwayo’s diplomatic strategy was in tatters with the annexation of the Transvaal by the British as he could no longer play the Boers and British against one another. However, he still attempted to maintain good relations with the British as he knew the Zulu would not be able to win a war with the Empire.

In late 1878 the British decided to act and in December of 1878 the British sent an ultimatum to Cetshwayo that they knew could not be accepted so that they would have justification for war. The most extreme of the demands in the British ultimatum were that the Zulu disband the regiments system and army which were the entire basis of Cetshwayo’s power.

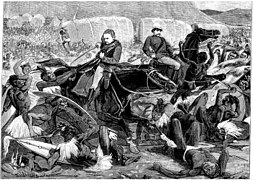

With the ultimatum rejected by the Zulu, the British invaded Zululand on the 11th of January 1879. Whilst the British would famously suffer some defeats, notably at the Battle of Isandlwana. Ultimately, they would crush the Zulu empire and end the independent Zulu state.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend