This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

27th March 1941 – World War II: Yugoslav Air Force officers topple the pro-Axis government in a bloodless coup

The First World War tore up the fabric of Europe and in the chaos of crumbling empires new nations were born. The war had begun after a Pan-Slavic terrorist had shot and killed the Austrian Empire’s heir to the throne, and some in the Serbian government were tied to the assassination.

This led to the declaration of war by Austria on Serbia and began the conflict.

During the war Serbia suffered tremendously; from 1915 it was occupied by Austria, Germany and Bulgaria, and it was hit hard by the Spanish Flu pandemic. As a combined result of the fighting, the brutality of the occupation, disease, and famine, around 28% of Serbia’s pre-war population died.

These incredible losses did not kill the dream of Pan-Slavic nationalists, people who advocated for all of the Slavic peoples to join together in one nation.

As the war drew to its end and Germany and Austria headed towards defeat, the multi-ethnic Austrian Empire began to splinter, and the South Slavs within the empire took the opportunity to break away and form the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. This new state lasted only 33 days and soon joined together with Serbia and Montenegro to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The goal of the assassins who had begun the war had been achieved. The new kingdom adopted the old Serbian royal family as its new monarchy.

While the new state was founded on the idea of ethnic unity, it became immediately apparent that almost none of the political factions had any idea as to how the new state would be constituted. Would it be federal or centralized? Would all ethnic groups be equal, or would Serbs dominate as the first among equals of the South Slavic people? Would the country be a monarchy or a republic? Would women get the vote?

These questions were not easily resolved, and the country became bitterly divided between its various political parties. It struggled to establish institutions and norms which were widely accepted across the country. Between 1918 and 1921 these debates raged. In 1921, however, the centralizing and pro-Serb parties managed to push through a new constitution in parliament with a 50% majority. This new constitution, known as the Vidovdan Constitution, was a victory for the centralizing, and monarchist forces, but it was aggressively opposed by the opposition, who boycotted the vote on the constitution, and in the case of the Croatian Republican Peasant Party, refused to accept it as binding. This constitution established the kingdom as a constitutional monarchy with a powerful but restrained monarch.

Once in place the government increasingly became dominated by pro-Serbian policy and the mostly Croatian opposition parties were harassed and suppressed in elections, with their political leaders repeatedly jailed and elections rigged in favour of the ruling party. This continued until December 1928, when things spiralled out of control.

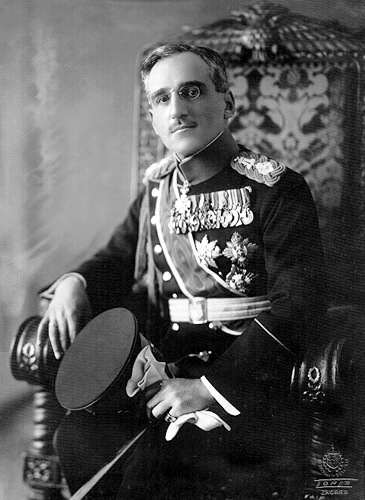

A dispute on the floor of the parliament saw a member of the governing party shoot five members of the Croatian Peasant Party, including its leader Stjepan Radić. The shooting outraged the king, who decided to intervene to end the fighting and ease ethnic tensions. On 9 January 1929, King Alexander I dissolved the parliament, suspended the constitution and installed himself as an effective dictator without legislative checks on his power.

Alexander changed the name of the country to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (the Kingdom of South Slavs) and by 1931 had a new constitution drawn up which left him with greater powers, while reintroducing the parliament. However, elections would no longer have a secret ballot, and half of one of the houses of parliament would be appointed by the king. He also worked aggressively to establish a more unified South Slav identity and end the ethnic factionalism. Nevertheless, he was still seen as far more pro-Serb than truly in favour of equality.

Croation opposition parties, which ramped up their opposition to this new government and demanded greater autonomy or even perhaps independence for Croatia, were met with heavy repression. By 1934 the king began to soften his hard-line on the Croat opposition and released their leader from prison, planning to introduce more democratic reforms and hopefully repair relations between Serbs and Croats. Before he could implement these, he was shot dead by a Bulgarian nationalist who was working with Bulgarian nationalist groups in Macedonia and the Croatian extremist group, the Ustaše.

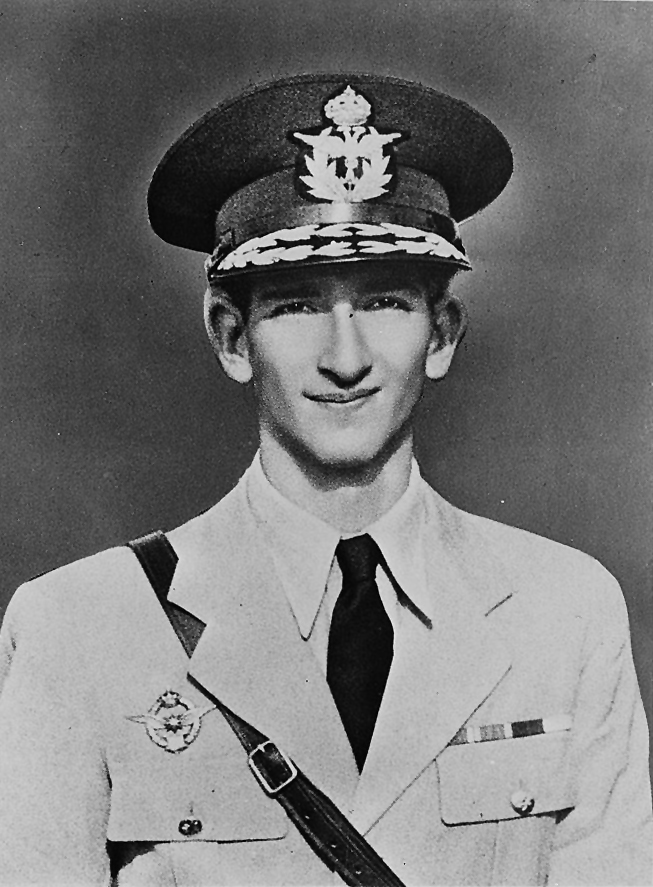

Alexsander’s son, Peter, was only 11 at the time and so Alexander’s cousin Prince Paul was selected as a regent to rule on the young king’s behalf until he came of age. Between 1934 and 1941 tensions between Croats and Serbs continued to grow, despite some devolution of power and the creation of Serbian and Croat sub-divisions within the kingdom. While Paul was more democratic and less pro-Serb, he found himself unable to reform the country sufficiently to end the tensions.

As all this was happening, the Nazi Party and Fascist Italy had begun their expansion across Europe. The Yugoslavs, concerned with their own troubles, attempted to stay out of the conflict. Italy however had in part joined the Axis with Germany because of their sense of betrayal at the end of the First World War, when the Allies had promised them lots of land in what was to become Yugoslavia but at the peace talks had sided with the Yugoslavs and gave Italy fairly minor concessions. As such Italy was hungry for Yugoslav territory.

In 1939 Italy had invaded Albania and was now positioned to attack Yugoslavia from both west and south. At the same time, Hungary and Bulgaria, which had both lost land to Yugoslavia in 1918, aligned themselves more and more with Italy and Germany.

The Yugoslavs were sympathetic to the French and British who had helped found their state, but Prince Paul saw the writing on the wall – that if the Axis decided to attack Yugoslavia, they would be able to invade from all sides and crush the Yugoslavs, whose only regional ally was Greece.

In 1940 after the fall of France to Germany and the invasion of Greece by Italy, Prince Paul was convinced by members of the army to sign a treaty with the Axis powers.

The army was convinced that if they aligned with Germany that the Germans would protect them from attack by Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria. Hitler for his part was worried that the Yugoslav army was strong and that if it and Greece were not pacified prior to his planned invasion of the Soviet Union, Germany would be open to attack from the south.

On 25 March 1945, the Yugoslav government signed the ‘Tripartite Pact’, becoming a formal member of the Axis. This was met with outrage across Yugoslavia, with people taking to the streets chanting ‘Better the grave than a slave, better a war than the pact’.

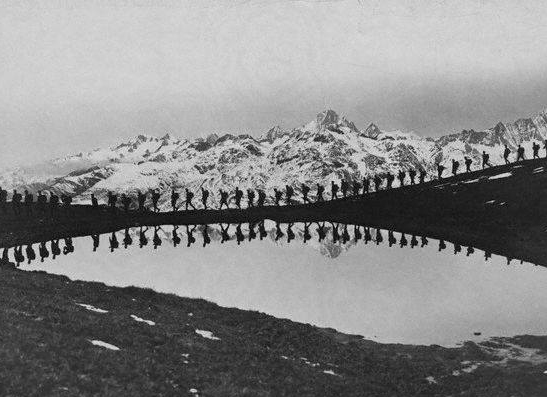

Some in the Yugoslav Air Force did not share the army’s view on the alliance with Germany and immediately began plotting to overthrow the government. In the early hours of 27 March, while Prince Paul was on holiday in Croatia, officers of the air force launched a coup.

The coup plotters quickly captured the capital Belgrade, and Paul’s wife and children, who were in the city. Fearing for his family’s lives, and desiring to keep the peace, Paul declined the offer of some Croatian army units to march on the capital and decided to surrender. He relinquished power and went into exile, first in Kenya, where he lived under house arrest, then in South Africa until 1949 and, finally, in Paris. The coup plotters declared the now 17-year-old King Peter as ‘of age’, and proclaimed a people’s revolution renouncing the Tripartite Pact.

Hitler immediately issued Führer Directive 25, which called for Yugoslavia to be treated as a hostile state and began giving clandestine promises of support to the Croatian nationalists.

Units were diverted from the staging grounds for the invasion of the Soviet Union and on 6 April 1941 Germany invaded Yugoslavia, crushing its army in 12 days. Yugoslavia was partitioned between Italy, Germany, Hungary and Bulgaria, and a Croatian state run by the Ustaše was formed.

Until the end of the war Serbian Nationalist and Communist Partisans would fight a brutal struggle against the occupying Axis and Ustaše, with support from the British and Soviets, causing great headaches for the German high command. In the end the communist partisans would take control of the country in 1945 with Soviet help and go on to establish the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia led by Josip Broz Tito.

Tito would hold the state together – but the scars left by the war years did not heal. With Tito’s death the Yugoslav republic collapsed into bloody ethnic strife.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend