This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

17th June 1885 – The Statue of Liberty arrives in New York Harbour

The Statue of Liberty or the Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World, has its roots in the two great American conflicts, the American War of Independence and the American Civil War.

The American War of Independence created strong relations between France and the United States, as it was only with the entry into the war on the side of the American rebels by Britain’s enemies, namely France, that the United States became independent.

These ties would only grow stronger when France threw out its own monarch in the French revolution of 1789 and became a republic, until 1804. During this early period of American history, its foreign policy was often divided between those who sought reconciliation with the British and those who supported the French republicans. The two nations developed a strong relationship on the idea that both saw themselves as beacons of liberty in a tyrannical world.

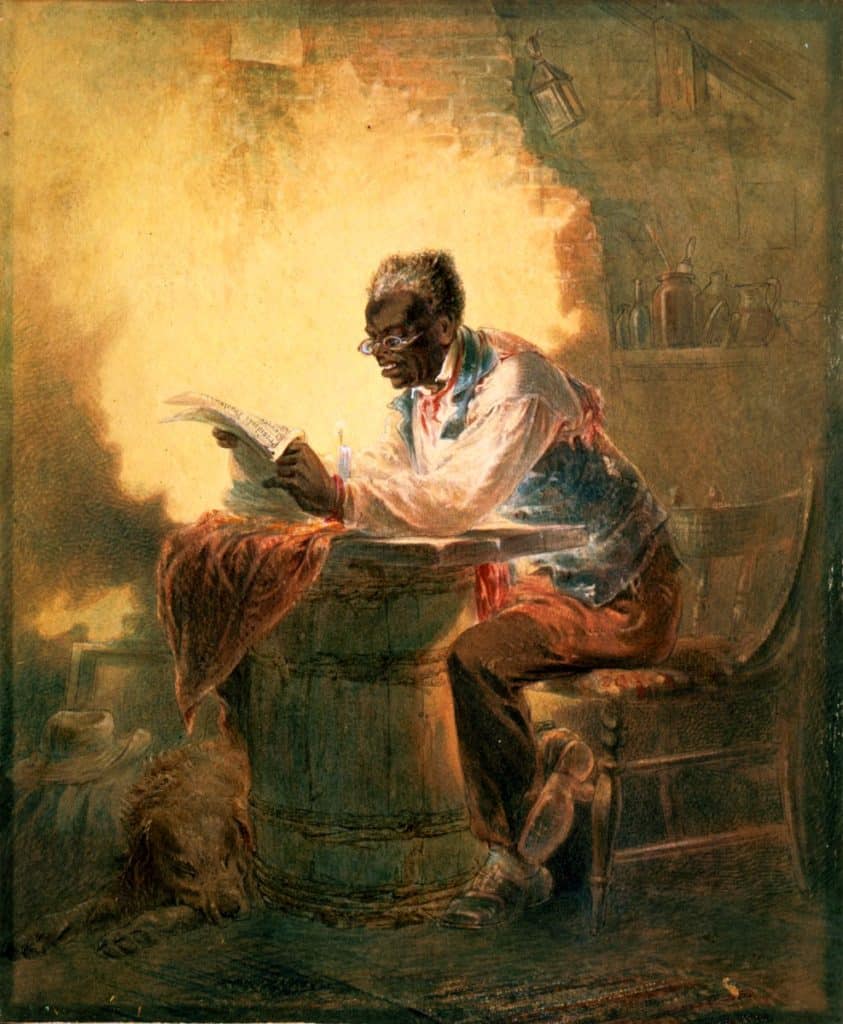

The true inspiration for the Statue of Liberty, however, would emerge from the American Civil War.

This conflict, while originally about preventing the splitting of the United States, as well as contestation for political power between north and south, became over the course of the war more and more about the abolition of slavery. With the Union becoming more closely associated with the fight to end slavery as the war went on, the Confederacy struggled to gain international support from major European powers like Britain, which were anti-slavery.

The end of the war with the abolition of slavery and the total victory of the Union, was celebrated across the world by anti-slavery activists.

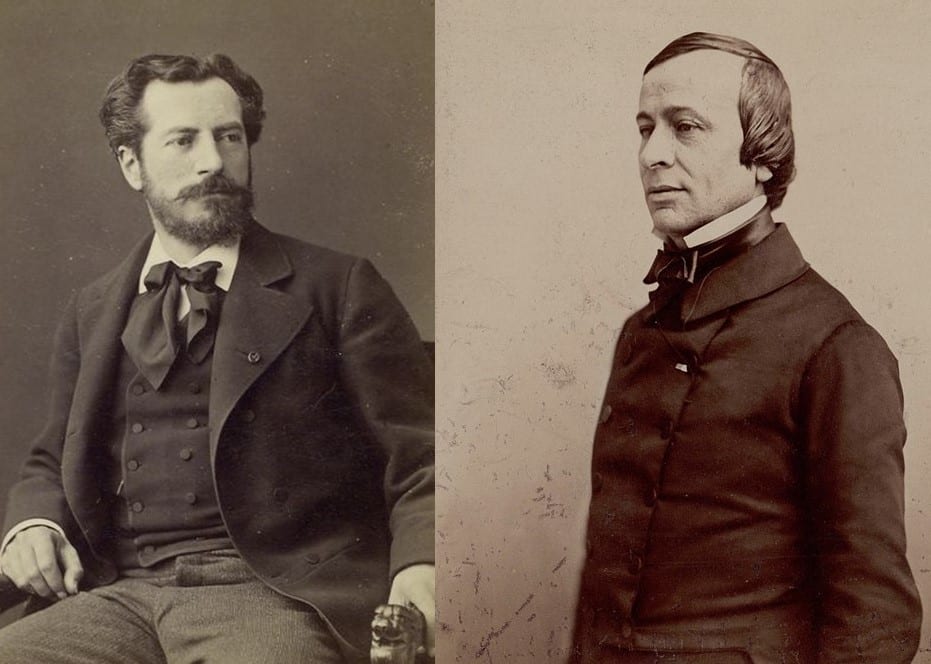

During a dinner, president of the French Anti-Slavery Society, Édouard René de Laboulaye, remarked to his friend, the French sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi, that something should be done to honour the Union’s victory and the freedom of the slaves.

Laboulaye suggested that any such monument should be a gift from France to the United States, which would hopefully also inspire the French to bring their government more in line with the ideas of the Americans.

Bartholdi, at the end of the American Civil War, was working on a similar project in Egypt where he hoped to get the ruler of Egypt to fund a statue at the entrance of the Suez Canal of an Egyptian peasant woman holding a torch with the title “Build Progress or Egypt Carrying the Light to Asia”, a work which would also serve as a lighthouse in imitation of the ancient Colossus of Rhodes.

Ultimately the project was deemed too expensive and cancelled in 1869, with a cheaper lighthouse built instead.

Bartholdi was delayed in pursuing the project for a few more years as he was drafted to serve as a major in the Franco-Prussian war in 1870.

Finally in 1871 Bartholdi, with letters endorsing him from Édouard René de Laboulaye, travelled to the United States to seek support for the Statue of Liberty idea from important Americans. During his trip across the US, he won much backing for the idea, including from President Ulysses S. Grant.

Bartholdi had identified the site of Bedloe’s Island, now Liberty Island, as a prime location as ships bound for New York had to pass the island to enter the harbour.

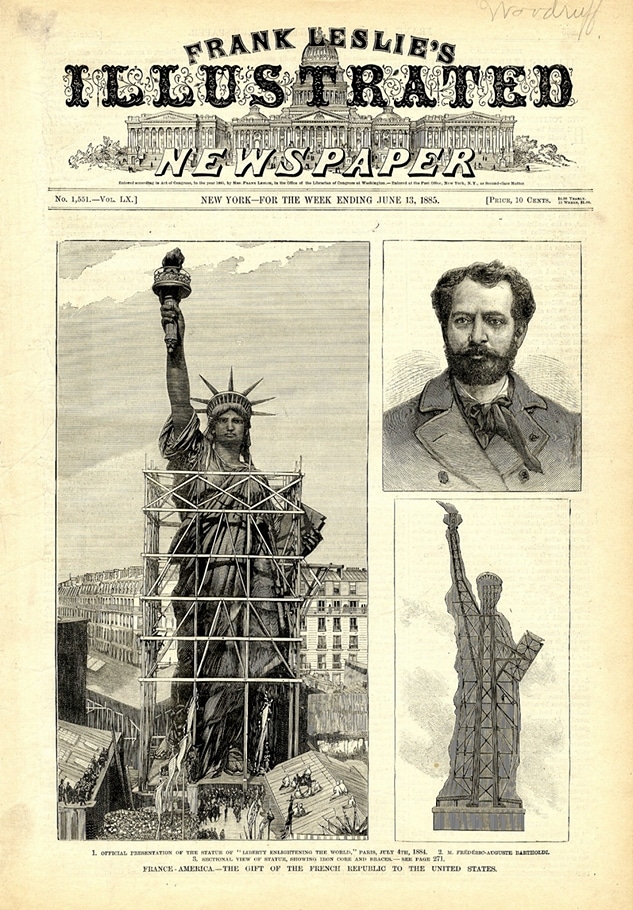

Bartholdi returned to France and in 1875 publicly announced the project, hoping to get public support for it in time for a celebration of America’s 100th anniversary. The French public would pay for the statue, the Americans for the pedestal. The fundraising was hugely successful and soon sufficient money was raised in both America and France to ensure the construction.

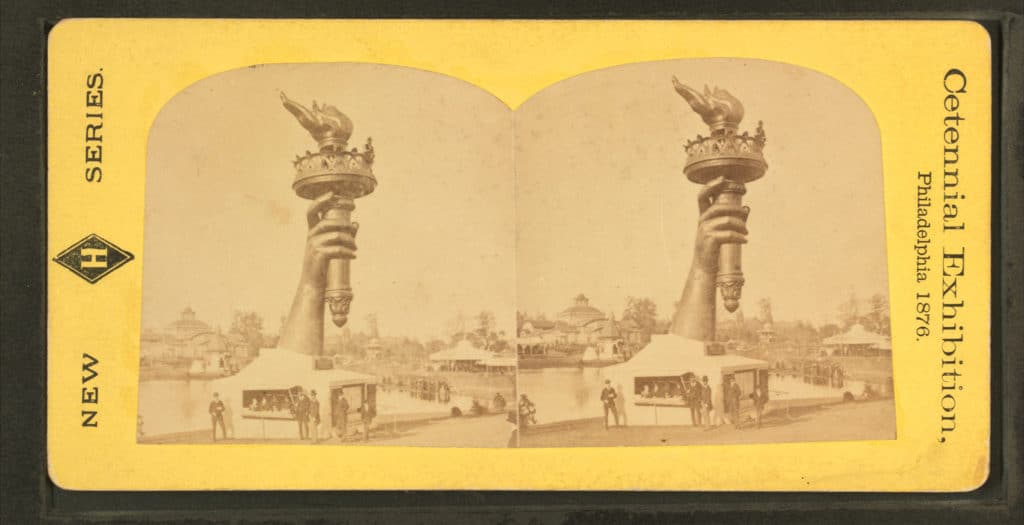

As the statue was constructed out of copper, various pieces were exhibited to the public to build excitement.

The disassembled statue arrived in New York harbour on 17 June 1885, and was welcomed by a crowd of 200 000 people lining the quays as the ship carrying the pieces came into dock. All in all, 120 000 Americans donated to the project, with 80% of these donations equalling less than one dollar, raising in total $102 000 (equivalent to more than $2,5 million today).

The statue was dedicated on 28 June 1886, with President Grover Cleveland presiding over the event. A massive parade was held in New York to welcome the statue, with hundreds of thousands in attendance.

The finished statue was well received, except for its torch which had originally been planned as a lighthouse but glowed far too faintly to be used and would not be improved until the 20th century.

Today the statue is an icon of the United States and still holds powerful emotional and political meaning for millions of Americans.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend