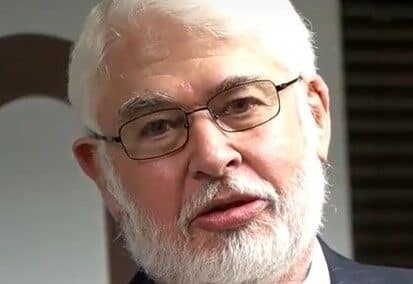

John Kane-Berman, who was born on the eve of apartheid and devoted his life to vigorously opposing the race nationalism of apartheid’s ideologues and, at their defeat, the illiberal impulses of their successors, has died aged 76.

His conviction in the power of ideas was central to his long association with the South African Institute of Race Relations. It remains a profound and lasting influence on the liberal cause, and the continuing efforts to achieve a fairer, prospering South Africa.

Said John Endres, CEO of the South African Institute of Race Relations: “John Kane-Berman leaves a profound legacy. As CEO of the Institute from 1983 until 2014, he was a fearless proponent of liberalism before, during and after South Africa’s democratic transition. He sharpened the SAIRR’s focus, put it on a sound financial footing and set it on the path that turned it into the potent force that it is today.

“His brave and unstinting commitment to the liberal cause inspired legions of South African liberals, myself included. John Kane-Berman was known for his eloquent presentation, exceptional memory, thorough command of his subject matter and exemplary discipline. He was demanding, setting the highest standards for himself and others, because he realised the importance of the project he was engaged in: to insist that nothing less than true non-racialism and personal freedom would allow the dignity and prosperity of all South Africans to flourish.”

Kane-Berman, the eldest of five brothers, was born in Johannesburg in 1946.

He was schooled at St John’s College in Houghton, and went on to study at the University of the Witwatersrand and, as a Rhodes Scholar, the University of Oxford. He grew up in what he described as a “happy, comfortable, and politically conscious family”. His father, Louis, had become a household name in South Africa as chairman of the Torch Commando, Second World War veterans who rallied to the cause when the Nationalists sought in the early 1950s to disenfranchise coloured South Africans in the Cape.

National Party leader and prime minister of the first apartheid administration, D F Malan, characterised the Torch Commando as “a most dangerous organisation”; Alan Paton fittingly described it as “the only white organisation the National Party ever feared”.

Kane-Berman would reflect almost 50 years later “that the Torchmen’s practical assertion of the right to free speech” had impressed him enormously, and was proof that, borrowing from Tennyson’s Ulysses, “freedom of speech, sword-like, longs to shine in use [and] not be left to rust”.

His life, Kane-Berman himself said, was really about opposition to the abuse of power and how its misuse hurt the most defenceless people. A clear memory was coming down to breakfast at the age of 14 to read about the Sharpeville Massacre in the Rand Daily Mail, and of how as a consequence of Anglican Bishop of Johannesburg Ambrose Reeves’ efforts to challenge the official account of the shooting, his parents then took in the Bishop’s son, Nicholas, his classmate, after the Reeves family had received death threats, making it untenable for the boy to remain at home.

Kane-Berman recalled that while there were not many liberals at St John’s among the boys, this was “not true of the staff and least of all the headmaster Deane Yates” who gave him some of his earliest experience of formal political resistance in making him chairman of the St John’s African Education Fund.

St John’s proved influential in Kane-Berman’s political education. As a schoolboy he went to listen to Beyers Naude, who had just formed the Christian Institute to oppose apartheid. The young Kane-Berman successfully challenged the college chaplains to reword a prayer which called for “the right solution to all the problems presented by the native and coloured peoples” to “the right solutions to all our racial problems” after telling the chaplains that those problems arose not from “native and coloured peoples” but rather from the attitudes of whites.

St John’s also gave Kane-Berman his first experience of journalism, when he was appointed editor of The Johannian. In the aftermath of Harold Macmillan’s 1960 visit to South Africa and his famous “Wind of Change” speech, Kane-Berman and his fellow editor Michael Arnold (who would go on to become the school chaplain) published Arnold’s poem on the “Wind of Change” theme in the school magazine, which read, in part:

“This gentle breeze doth purge the desert air / Embalming flowers with a fragrance fair / A fragrance such as rank hyenas know / A rancid stench a polecat would forego”, the latter line being a reference to Die Burger editor Piet Cillié’s description of South Africa after Sharpeville as the “polecat of the world”.

Later, while in the sixth form, he started a school newsletter titled Sixth Sense which, he recalled, “naturally specialised in publishing provocative and controversial stuff”.

Encouraged by Deane Yates, and his parents, to write more of this type of thing, he was particularly pleased with his parody of Mark Anthony’s rabble-rousing speech in Julius Caesar, which – published in the Rand Daily Mail, from which it went on to be quoted by Alan Paton – read as follows:

Friends, citizens, countrymen, lend me your ears

I come to bury Freedom, not to praise her …

The noble Vorster

Hath told you Freedom was a Communist

If it were so, it was a grievous fault

And grievously hath Freedom answered it

And Vorster is an honorable man …

His education continued at Wits, where in his first year he was prevailed upon by fellow Johannian Alan Murray to stand for the Students’ Representative Council (SRC). This he did successfully, later becoming its President, in the course of which he met the young University of Natal lecturer, Lawrence Schlemmer, who would go on to become President of the South African Institute of Race Relations, and also Charles Simkins, who would go on to become the chairman of its board. At Wits, Kane-Berman led campaigns against social segregation and government interference in higher education, earning him the wrath of several ministers. He himself was accused of being a “totalitarian liberal”, while the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) – to which Wits and several other campuses were affiliated – stood accused of being a front for “foreign ideologies [with the risk] of being manipulated by pro-communist elements”.

Despite Kane-Berman’s efforts, social segregation was used as a tool to undermine NUSAS, and when in 1967 Rhodes University refused to allow delegates to a NUSAS conference to eat together, he supported Steve Biko’s decision to break from NUSAS and launch the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) – on which Kane-Berman reflected decades later that the ensuing rise of Black Consciousness had been “a healthy and necessary development”.

The 1968 campaign he helped lead against the decision by the University of Cape Town to rescind the appointment of UCT graduate Archie Mafeje to a lectureship at that university was particularly influential.

Kane-Berman recalls his pledge to stand with UCT students in protest being met with “thunderous applause” by a packed Great Hall. That campaign led to tense student protests on Jan Smuts Avenue that attracted responses ranging from offers of support from the Hells Angels to denouncements and threats from the police minister, S L Muller, and Prime Minister John Vorster. Those confrontations culminated in a meeting with Vorster at the Union Buildings, an encounter Kane-Berman (who was accompanied by two colleagues) described as “less than gracious”, during which Vorster “exploded”, telling him that what he was doing “would not be tolerated”. The government feared the kind of student protests that had erupted earlier that year in Paris.

When, amidst the ongoing protests, he received a letter telling him that “so long as there is opposition to racialism and the clampdown on human freedom and expression, the government has not won”, he was very touched. The author was Raymond Tucker, who would later go on to become honorary legal advisor at the South African Institute of Race Relations.

Whereas Kane-Berman had successfully seen off attempts from the left and the right to capture NUSAS, it eventually fell to the left following his graduation. The Sunday Times described NUSAS “as one of the most enlightened and courageous bodies we have ever had in South Africa…a voice crying out against injustice and inhumanity”, while Kane-Berman, five decades later, described its collapse as the loss of a “liberal kindergarten” from which “South Africa has not recovered”.

From Wits it was off to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. He found his Oxford years to be much slower in contrast to the fast-paced drama of Wits student politics, and the local issues were mundane by comparison, but he revelled in strolling the college lawns and river banks with friends from St John’s and Wits. He read extensively, recalling how he had been particularly influenced by William Sheridan Allen’s Nazi Seizure of Power, given the parallel with South Africa in how people could become conditioned over time to accept what they might not immediately have been prepared to accept. Kane-Berman later wrote that “white South Africans had been corrupted by such conditioning”.

On his return to South Africa, many of the books in his luggage were seized by customs officials – although he had been careful to send already banned publications by sea, and these arrived safely.

Shortly after that return he met Pierre Roestorf with whom, forty-one years later, he entered into a civil union performed by Constitutional Court judge Justice Edwin Cameron, who’d been in the army with Pierre.

With Oxford behind him and being exposed once again to the South African reality, Kane-Berman felt that four things should be done by whites to counter government conditioning: defend the rule of law even in the face of bannings and detentions; assist black trade unions; pump the idea of majority rule into the public domain; and build contacts and friendships across the colour line.

While still abroad, he had had a visit from prominent journalist Benjamin Pogrund, who’d suggested he join the Rand Daily Mail. But his friend and fellow Old Johannian Clive Nettleton, who was assistant director of the South African Institute of Race Relations, persuaded him to join its research department instead. A report he wrote at that time led to a meeting with Graham Hatton, then assistant editor of the Financial Mail, who offered Kane-Berman a job that he later accepted; he ended up taking over the labour beat from Bob Nugent (Iater Judge Nugent), who was leaving to do his LLB.

Working under the tutelage of editor George Palmer and with the protection of the reputation of the Financial Mail, Kane-Berman was able use his position as a weapon, and to say things that might otherwise have been banned (his passport had already been confiscated, and though later returned, was valid for only one year at a time – following, Helen Suzman told him, approval by the security police). When in 1974, for example, Foreign Minister Pik Botha told the United Nations that “my government does not condone racial discrimination”, Kane-Berman sent a photographer to take pictures of the choicest apartheid signs to use on the cover and wrote in an accompanying piece that “(discrimination) is at the very heart of our society … it governs every facet of our lives”. He knew that even John Vorster read the Financial Mail and understood the impact his exposés would have in shutting down the government’s space to whitewash apartheid.

It was while at the Financial Mail that he wrote his famous book on the Soweto uprising of 1976, Soweto: Black Revolt, White Reaction.

From the Financial Mail, Kane-Berman moved to freelance journalism before, in 1983, being prevailed upon by Jill and Ernie Wentzel to become CEO of the South African Institute of Race Relations.

Once there, he faced three formidable challenges. The first was that the Institute was essentially bankrupt and he needed to rebuild its finances against incredible odds. This he did with spectacular success, to the point that at his retirement it boasted a war chest of over R40 million. The second was pressure from among his staff and structures to move further to the left, a risk he deftly disabled in a battle best set out by Jill Wentzel in her book The Liberal Slideaway, thus succeeding in reinforcing the Institute’s reputation as a liberal institution. The third was pressure to join in the blanket endorsements of the United Democratic Front (UDF) and the African National Congress (ANC), which the bulk of civil society and the global anti-apartheid movement were doing. But Kane-Berman knew that this would be a mistake, as lurking within those institutions were ideas sufficiently antithetical to freedom that South Africa risked trading one form of corrupt authoritarianism for another.

“This was a remarkable piece of foresight,” noted Kane-Berman’s long-time colleague, and successor as CEO of the Institute, Dr Frans Cronje, “that took almost 30 years to be vindicated, but for which John paid a heavy personal price.”

Instead of outsourcing the Institute’s moral and intellectual faculties to the UDF, Kane-Berman chose to keep these within the Institute and use the organisation to plant ideas that at the right moment could become the underpinning of a more just and free South African order. In doing so, he became a remarkably brilliant practitioner of battle-of-ideas theory, which holds that the winner of any great political or ideological contest is ultimately the side that injects the greatest volume of compelling argument into the public domain.

To this end, it was while at the Institute that Kane-Berman delivered the balance of his 700 public speeches and wrote innumerable reports, hundreds of thousands of words in newspapers, and three of his four books, with Silent Revolution, published in 1989, being arguably the most influential for detailing how the resistance of ordinary people had become the most important and influential factor in defeating the apartheid system.

That work continued after 1994. By the time he retired as CEO in 2014, the Institute was securing scores of daily citations, making it the single most influential source of liberal ideas in the South African public domain.

Should a reformist government come to power in South Africa at any point in the next decade and succeed, it will do so largely because its policies reflect the ideas Kane-Berman made sure the Institute continued to press for even after liberation in 1994.

As a courageous and challenging public intellectual, John Kane-Berman straddled the old and new eras of modern South Africa with an unerring willingness to expose both to the same keen analysis. The vigour and conviction he brought to making the case for a better 21st century South Africa welled from his acute knowledge of and intimacy with the grim country it had been.

Kane-Berman had an enormous influence on South Africa’s political evolution. It was at his behest that Robert Kennedy visited South Africa in 1966, placing a glaring spotlight on the country as he, the brother of the most famous man in the world, stood with the anti-apartheid cause.

His leadership within NUSAS in its confrontation with the government set the precedent for student politics of the next 30 years, and helped define its role in defeating apartheid.

As chairman of the youth branch of Helen Suzman’s Houghton constituency, Kane-Berman worked on the 1966 campaign (sleeping at times with a baseball bat in the campaign office) that underpinned her political rise and thereby that of the Progressive Party, as well as all that followed, including – as one of the most important consequences – South Africa’s present official opposition.

His relationships in Washington, especially with former Assistant Secretary of State Chester Crocker, had a disproportionate influence in shaping American policy towards southern Africa over the latter two decades of apartheid. It was Kane-Berman who suggested the questions that Margaret Thatcher used to hammer PW Botha at Chequers in 1984.

While at the Financial Mail and then at the South African Institute of Race Relations, Kane-Berman made sure that there was nowhere for the apartheid government to hide from the facts about the consequences of its policies. Later, his intellectual influence through the Institute was a large part of the reason why in the 1990s two nationalist political organisations settled on a broadly liberal Constitution for South Africa.

Kane-Berman delighted in how the powerless had turned the tables on the powerful and he was very glad to know that he had helped to create circumstances to aid them in doing so in South Africa.

His weapon, which lives on in the organisation he was so influential in shaping, was ideas. He understood that these mattered above all else and that unless you paid attention to them you could not understand, let alone counter, the absurdities that politicians got up to.

Kane-Berman’s own unfussy phrase, “I myself never had any weapons, other than words” in his 2017 memoir, Between Two Fires – Holding the liberal centre in South African politics, is a fitting epitaph for one of late 20th century South Africa’s most notable warriors in the battle of ideas, a liberal thinker who was fearless and unhesitating in devoting his very considerable armoury of words to a lifetime’s campaign for justice and truth.

- This article has been edited, correcting the reference to Kane-Berman’s involvement with the National Union of South African Students (Nusas).