If we can’t be certain of what will happen in the years to come, we do know that it will depend on the choices we make today.

One of the more interesting sub-genres of science fiction is that of future history, where a writer speculates on what is going to happen in the years to come from the perspective of that imagined future.

Of course, future history becomes alternate history eventually, but it is a fun genre to read and think about. Some of the greatest science fiction (or speculative fiction, to use its more inclusive title) books have been written as ‘future history’. One such example is Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men, publishedin 1930. This book attempted to be a future history laying out what Stapledon imagined would happen to humanity over the next two billion years.

Most future history does not try to be so ambitious and will only attempt to flesh out what will happen in the next few decades. Some of the greatest novels about politics are future history, and sometimes their speculation can be eerily prescient. For example, It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis, and published in 1935, imagines a demagogic president being elected in the United States. Depending on which side of the political aisle you find yourself on, one could see this having many parallels to what is happening in America today.

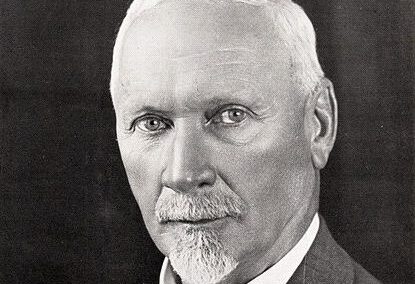

South Africa has had its fair share of political future history, too. Perhaps the seminal South African book in this genre was When Smuts Goes by Arthur Keppel-Jones. In this book, written just after the end of the Second World War, Keppel-Jones correctly predicted that the National Party would beat the United Party led by Jan Smuts (although he thought it would be four years later than it was in reality). What Keppel-Jones predicted was even worse in his imagination than what actually happened. South Africa soon becomes a fascist dictatorship, which is eventually overthrown through violent revolution – assisted by Western powers – with the country ending up as an undeveloped, insular backwater.

Lester Venter revisited the concept in the late 1990s. He wrote When Mandela Goes, which imagined what would happen when Nelson Mandela retired. In his scenario, the African National Congress (ANC) splits, with a more radical, left-wing party emerging in revolt against the ANC’s fairly orthodox economic policies. This new party – the African National Labour Party (Anlap) – would become the governing party and lead South Africa down the failed path of statism, with economic growth dwindling. Perhaps Mr Venter was wrong about the mechanics, but he predicted South Africa’s spluttering path today.

There was also South Africa, 1994 – 2004: A Popular History, written by Professor Deon Geldenhuys of the former Rand Afrikaans University, shortly before the first democratic elections of 1994. Using the pseudonym Tom Barnard, his tale has Afrikaners violently seceding and establishing a state in the Northern Cape – Orania – and threatening to use weapons of mass destruction on South African cities. The international community intervenes to prevent the conflict going nuclear. The book concludes with Rump South Africa renaming itself Azania, and the sitting Azanian President being overthrown in a coup.

It is not only South African authors who have tried their hand at predicting what South Africa’s future holds. Larry Bond, a frequent collaborator with Tom Clancy, wrote Vortex in the early 1990s. In Bond’s scenario, the reform-minded South African President and most of his cabinet are killed by ANC guerrillas. This leads to a hard-liner, and secret Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging sympathiser, becoming President, with South Africa reinvading Namibia. Cuban forces counter-attack and invade South Africa, with both sides using weapons of mass destruction. Eventually the US and UK invade to restore order, and a democracy is finally established.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most optimistic ending was that written by Bond, an American.

My senior colleague, Frans Cronje, is well-known for his scenario planning, although his is of a more academic nature than what is described above.

But what does lie ahead for South Africa? We have certainly emerged in better shape than anything envisaged by Keppel-Jones, Geldenhuys, Venter, or Bond. If one had access to a time machine and brought a South Africa-watcher from the mid-1980s to South Africa today, they would probably say, on balance, things had turned out well.

But the bullet many thought would hit South Africa in the last century, might only have been delayed, rather than dodged.

Although South Africa has succeeded on many fronts in the post-apartheid period, there have also been failures, especially since Jacob Zuma became President in 2009. Education for most South African children is dismal, economic growth has stalled, and unemployment and poverty remain high. In addition, minorities, especially Indians and whites, are increasingly being scapegoated for the country’s failures.

What would a future history look like, predicting a South Africa twenty or thirty years from now? The only certainty is that the African National Congress (ANC) will lose power – perhaps as soon as the next election in 2024. The rest we cannot know.

Will the country embark on the path of reform and realise its economic potential, while protecting democracy and individual rights? Or will it follow the path of countries like Zimbabwe and Venezuela, with increasing government encroachment and erosion of civil and other rights, until it becomes a failed state? Or perhaps we’ll take more of a middle path, a country that continues to stagnate and bumble along?

The beautiful thing is that this history has yet to be written. But, looking back twenty or thirty years from now, will the story of our next few decades be a tale of success or failure? If the future is by definition unknown, what we do know is that it depends on the choices we make as a country and as South Africans today.

Marius Roodt is the Head of Campaigns of the Institute of Race Relations.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.