However good people may be, the societies they constitute cannot prevail against bad ideas unless they muster the will to reject them.

The wriest aesthetic conceit in the urban landscape of post-Civil War Beirut is the various forms of speckled or dotted motifs on the façades of new gleaming high-rise buildings in the Lebanese capital’s resurgent downtown district.

Far from being incidental decoration, it soon becomes apparent, these motifs mimic and in their way memorialise a conflict that left virtually every building chipped, peppered and gashed by shells, rockets and bullets fired at close range in deadly exchanges between the feuding parties – fellow citizens – in the war that lasted from 1975 to 1990.

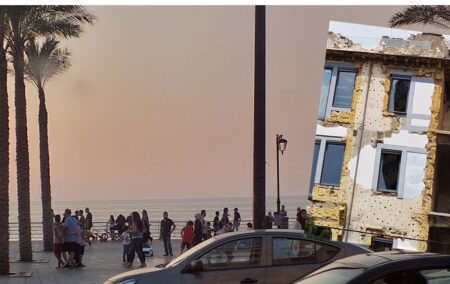

The potency of those wry, not wholly decorative motifs as tokens of the get-and-up-go (and, possibly, don’t-look-back) post-war recovery is sharpened by the occasional sight all these years later of an abandoned city building, stranded in its dilapidation and still spattered with bullet holes, or missing chunks of its former self. Looking at some of these wrecks, it’s hard to imagine the society that created them managing to foster anything beyond embittered memory.

And yet, along the Corniche, the city’s Mediterranean seafront, thronged with summer crowds, there’s little outward hint of a crisis of nationhood.

Here, among other splendours of post-1990 reconstruction, is celebrated Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid’s mesmerizing Beirut Souks building, still under construction, but already entrancing. Its seemingly elastic, distinctly humanoid, outline – mammoth, but suggestive of a supplicant child, humbled before a greater, gentler idea (the late Hadid’s actual inspiration is said to have been a twisted rattan basket), seems to confirm the idea of a country that is succeeding out of genuine civic optimism.

But fleeting impressions can be misleading.

To spend just a week in a country – as I did in Lebanon at the end of June – provides the scope for perilously slight insights that have every chance of being too shallow to have any real meaning.

I have no doubt the truly notable hospitality and easy-going generosity of the Lebanese is an authentic measure of who they are.

I was told on several occasions by different people and in slightly different ways that in Lebanon’s long history, the society tolerated one foreign imposition after the next – among them, the Egyptians, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Turks, the French – for their interest was never territorial but mercantile, and they lived or learned to live for trade, cutting deals, doing business with whoever was willing, and tolerating what they believed they couldn’t change.

‘After every crushing blow,’ one Beiruti told me, ‘the Lebanese always built themselves up again, wanting only to trade and profit for their own comfort and esteem, to live life to the full.’ He paused. ‘They are filled with the spirit of life … but it also makes them terrible.’ They were terrible, he explained, not as people, but as citizens who tolerated what was often intolerable.

A day later, journeying inland towards Bcharre, the same man pointed to a vast, ugly wound in the slope of a mountain only parts of which retained the recognisable elements of ‘countryside’, and said flatly: ‘Every politician in Lebanon owns a quarry.’

I thought of South Africa, then, and the toleration of bad ideas that are costing our own reconstruction so dearly.

A resident described how, because of regular daily power cuts by the State energy supplier, Lebanese citizens pay two electricity bills every month, one to the State supplier and the other to whichever private power supplier has set up generators to fill the gap in their suburb or village. If that seems a workable arrangement, the real problem is that the private suppliers are now accused of actively sabotaging every attempt to reform the national energy generator.

It came as no surprise on my return to read of activists no less than planners and architects who are among those who worry about the loss of soul, the erasure of authentic Beiruti life, in the headlong rush to modernise the capital, to clear aside the old stuff, and wish its history away.

The biggest problem, not unlike South Africa’s, appears to be a coupling of unworkable political ideas with deep-seated identity politics, and the rampant corruption they breed.

Key figures in the political elite (representing no fewer than 18 Christian, Muslim and other religious sects) are heavily invested in a post-war renovation that is said to make more sense in dollar terms – for themselves – than in any real founding of a modern, peaceful, self-assured future.

Writing in January, American University of Beirut scholar Michael Arnold described a political system that ‘mandates that cabinet decisions be passed by a two-thirds majority, effectively institutionalising political deadlock, which has more often than not been the case, particularly in the post-civil war era’.

Despite some electoral reforms, ‘there is currently no political will (either) among the political elite (or) the population for broader reforms. The prevailing fear is that it would re-awaken tensions from the civil war that remain buried just below the surface’.

Instead, the current system ‘keeps Lebanese politics and the economy locked in a parasitic and symbiotic relationship vulnerable to corruption, identity politics, and near-constant external manipulation’.

Arnold wrote: ‘Political apathy is high, and the dependent patron-client style relationship between political leaders and their respective communities only furthers the unwillingness of the citizenry to entertain the idea of substantial political reform.’

Among the consequences are dire economic conditions: a debt-to-GDP ratio of 150%; a current account deficit of around 20% of GDP; nearly a third of government spending going to interest payments, and another similar percentage going to the wages of a bloated public service.

Meandering in the streets of Beirut, Byblos or Zachle among the friendliest and most generous people you could wish to meet, the real scale of this larger crisis is not obvious. That’s reminiscent of South Africa, too.

Among the first things I read on my return was a column by my senior colleague Frans Cronje, which, under the circumstances was sharply resonant.

‘South Africa cannot turn itself around and become a truly free and prosperous society,’ he wrote, ‘within the bounds of the hegemony of ideas forced upon the country by the ANC. That way we are doomed to a future of going through the motions of tinkering with policies that will never work – as the country sinks around us. Central now to any prospect for real political and economic recovery is rewriting the rules of that game, because only if that happens does it become a game that can be won.’

Epilogue

Just over 10km from the bustle and almost likeably idiosyncratic mayhem of central Beirut’s traffic, the hill town of Beit Mery, some 800 metres higher up on the wooded slopes of Mount Lebanon and a summer resort since the time of the Phoenicians, seems a world away. It was from here that my wife Sharon’s grandfather, Lutfallah, emigrated to a war-torn South Africa more than a century ago to start a new life, settling eventually in Ficksburg in the eastern Free State.

Returning to Beit Mery is something of a pilgrimage for the South African Sorours – and, for most of them, their first sight of the storied villa of great-grandfather Assaf, a blind stone mason still celebrated in a small way for having produced the longest window mullion in the whole village from a single piece of stone, still there after all this time. Nearby is the Greek Orthodox church at which young Lutfallah served as a bell-ringer before departing for a distant and barely imaginable life in Africa.

St Elias is a marvel, quite plain on the outside – the biscuit-toned west wall broken only by the old bell jutting in its belfry into harsh light of the summer sky – but glittering within, with gilded icons and murals and the gleam of sculpted wood, some of it bearing traces of an uglier past, parish priest Fr Hareth Ibrahim reveals.

Pointing up to the cedar tracery of an upper panel in the rood screen, Fr Hareth identifies a bullet hole that dates to the 1860 strife characterised as the massacre of Christians by their Druze neighbours.

Legend has it that it began with a heated dispute over a game of marbles between two young boys, one Christian, one Druze. When their fathers walked in on the argument, it is said, they took sides with a familial vehemence that within days became a communal one. There was, of course, a broader historical context – of identity politics, fixed beliefs and dangerous thinking about differences between people.

In the 15 minutes it took Fr Hareth to give an account of that bloody feud and the struggles of St Elias to rebuild itself and restore a local history ‘that can speak for itself’, he brought his audience from 1860 to 2019.

‘So, pray for us,’ he said without a pause. ‘This is the land of …’ – and here, unfortunately, his next word is indecipherable in the recording I made of his sometimes hard-to-follow account. But there’s no real uncertainty about what he meant, for he added: ‘When it’s going to stop … we don’t know when.’

This is Lebanon, he implied, and Lebanon means nothing is wholly assured.

Not for the last time, I thought of South Africa again, and the risk that, however good people may be, the societies they constitute cannot prevail against bad ideas unless they muster the will to reject them.

Morris is head of media at the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.