Human rights won’t stand a chance in South Africa if the institution that is meant to defend them muddles defending free speech with validating racial incitement.

This is the risk that emerges all too clearly from the findings of the South African Human Rights Commission on claims of hate speech against EFF leader Julius Malema.

As we made clear in a media release last week, the IRR agrees with the Human Rights Commission’s conclusion – that Malema’s racially inciteful comments fall within the permissible limits of free speech – but we disagree strongly with the Commission’s apparent reasoning that the EFF leader’s comments are permissible because they are valid in the context of South African history and the country’s present socio-economic circumstances.

The Commission’s muddled thinking meant an opportunity was lost to strongly assert the indivisible human rights of all South Africans, and to warn of the risks posed to them by the kinds of racially hateful ideas that have become Julius Malema’s stock in trade.

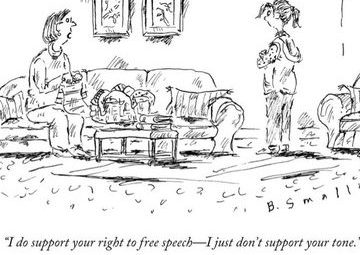

Our position is very simple: We defend free speech not to defend what people say, but that they can say it – and therefore that others can dispute it. This is the basis on which we spoke up over the past year for the right to speak freely of none other than Julius Malema himself, and his ideological soulmate, Black First, Land First leader Andile Mngxitama.

The principle at play is that while there is no doubt that some ideas can be dangerous, banning any idea always is – if only because it is only when dangerous ideas are heard that there is any chance of defeating them and, thus, preserving human rights.

This is the argument we would have hoped the Human Rights Commission would make, but it veered instead towards legitimating sentiments that are contrary to the letter and spirit of human rights protections in the constitution.

The key problem arises from the Commission’s arguing that the context of statements is important. That is perfectly true, but in a properly limited sense.

The context of any statement is important only in assessing whether it passes or fails the freedom of speech test – the risk the statement might pose – not in determining whether the content is approvable or not. That’s a huge difference.

Permissibility is not a question of weighing the validity of the content, but weighing the effect of it – and the risk to a free society of allowing it, or disallowing it.

Thus, in going down the ‘validity’ path, the Commission argued: ‘Robust speech must be protected for those who remain structurally marginalised to be able to express their moral agency through expression that conveys anger or frustration at persistent societal injustice.’

This is quite wrong on one count, and problematic on several others. First, robust speech must be protected for all citizens to ensure liberty is sustained.

There can be no free society where some have more rights than others. That’s the nightmare George Orwell illustrated in Animal Farm, and which is tragically evident in history, not least our own.

In going down this path, the Human Rights Commission implies that racial hate serves the interests of what it calls the ‘vulnerable black population group, which remains predominantly poor and landless’, and that it may be legitimate to racially abuse Indian South Africans because ‘66% of Africans remain poor, compared to approximately 6% of Indians’.

The virtues of free speech and human rights are brusquely set aside when the focus is turned to trying to validate the content of what is said – in this case, racially inciteful statements – by explaining it away as a rational response to socio-economic conditions.

Even if it could be argued that white-skinned people or people of Indian extraction can be blamed for the immiseration of black South Africans, it is completely unreasonable to think that this allows anyone to engage in racial stereotyping, incitement and hateful language.

That is simply an invitation to society to indulge in racial conflict – at the cost of the very human rights the Commission is meant to defend.

The irony, of course, is that – were one to weigh the merits of the Commission’s reasoning – there is a strong argument that it is not white people and Indians who are to blame, here, but the majority of voters who keep supporting a party that has led the country to its present crisis of low growth, soaring unemployment, crumbling infrastructure, corruption and rampant ineptitude.

Thus, on these grounds, offering special protection for those who are ‘structurally marginalised to be able to express their moral agency through expression that conveys anger or frustration at persistent societal injustice’ has nil to do with inciteful speech directed at powerless minorities.

It should be enough for South Africans to say: we are a free country, we let people say what they think, and if it’s racially hateful, we reject it. It’s not enough to say, as the Commission did, that the statements it weighed were ‘offensive and even disturbing’, or ‘quite offensive’, or that ‘public figures should refrain from making statements that erode social cohesion’ when its findings contrive to provide analysis that leans towards validating such offensive and erosive ideas.

The effect of seeming to justify racial incitement on rational grounds is dangerous for society; for any politician to talk of killing people, or to class an entire race group as morally deficient, is a danger – so long as it goes unchallenged, or is somehow offered the lifeline of technical, legal or socio-economic legitimacy.

Hateful rhetoric erodes human rights, and deserves firm, public repudiation. The Human Rights Commission’s timid and wrong-headed response does not inspire confidence in its grasp of what is at stake.

It is possible, as the IRR has demonstrated throughout its existence, to have the most robust conversation about race, socio-economic disparities, history, apartheid, failures of government, or the moral and other lapses of the electorate, in a rational and civil way that does not invoke or in any way justify racial stereotyping, race baiting or inciteful language.

This should be the benchmark of our human rights culture.

Michael Morris is head of the media at the IRR