This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

13th June 1325 – Ibn Battuta begins his travels, leaving his home in Tangiers to travel to Mecca

Ibn Battuta, depicted in an illustration by Léon Benett in Jules Verne’s book of 1878, “Découverte de la terre” (Discovery of the Earth)

Abū Abd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abd Allāh Al-Lawātī, more commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was one of the medieval period’s most well-travelled people who wrote some of the most fascinating and useful descriptions of the Islamic world of his time.

Ibn Battuta’s early life is not well documented, though he was known to be a Berber of North Africa from what is today Morocco and that he came from a family of Islamic legal scholars.

On 13 June 1325, he set out on the hajj, the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca. This journey would ordinarily take around 16 months; Ibn Battuta, however, would not return home for 24 years.

Writing of his departure from home, he later said:

“I set out alone, having neither fellow-traveller in whose companionship I might find cheer, nor caravan whose part I might join, but swayed by an overmastering impulse within me and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries. So I braced my resolution to quit my dear ones, female and male, and forsook my home as birds forsake their nests. My parents being yet in the bonds of life, it weighed sorely upon me to part from them, and both they and I were afflicted with sorrow at this separation.”

Battuta hitched rides with caravans and travelled along the north African coast by land.

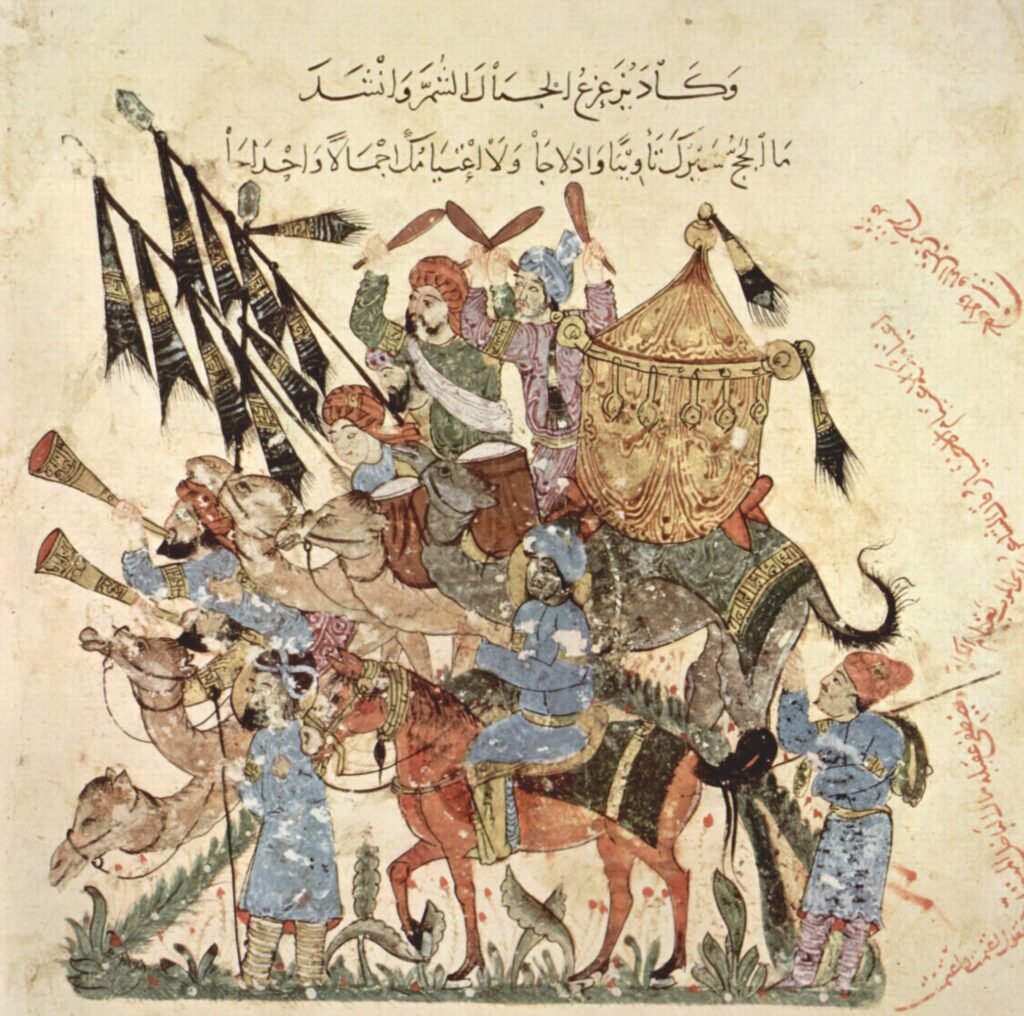

A miniature from al-Wasiti’s Maqamat of Al-Hariri of pilgrims on a hajj, circa 1236/37

In Sfax he got married, but left due to a squabble with his new bride’s father. This was a pattern he followed throughout his travels, often marrying a woman in a new city he’d travelled to and then divorcing her when he moved on. He would leave a string of abandoned women and children in the course of his travels across the Islamic world.

He eventually reached Mamluk-controlled Egypt, and stayed in the wealthy cities of Alexandria and Cairo, before taking a trip down the Nile.

The route to Mecca via the south was blocked by a rebellion in southern Egypt. Consequently, he changed direction and headed north to Mamluk-ruled Damascus in Syria, a city which once was the centre of the Islamic world as the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate. He then joined a caravan to Medina across the Arabian desert.

Finally in October 1326, Battuta reached Mecca, and would spend a month there taking part in pilgrimage activities.

With his mission completed, Battuta could have gone home at this point, but as his thirst for adventure had not yet been quenched he decided to continue travelling around the Islamic world.

He joined a caravan out of Mecca headed for Iraq, at the time under the rule of the Ilkhanate, one of the pieces of the Mongol Empire. There he visited the holy site of Najaf, the mausoleum of Ali, the 4th Caliph in Sunni Islam and the central figure of Shia Islam.

From there he went to Mongol-ruled Iran, travelling through the flourishing cities of southern Persia. This was a land which had not too long ago been ravaged by the Mongol invasions, but the southern cities had surrendered and so were left untouched by the Mongol armies.

After this he returned to Iraq and spent time with a Kurdish mystic in Mosul and then visited the seat of the Caliphate, Baghdad a city which was much reduced after its brutal sack by the Mongols 70 years prior. From Baghdad, he returned to Mecca for the 2nd time, and would spend several years in the city.

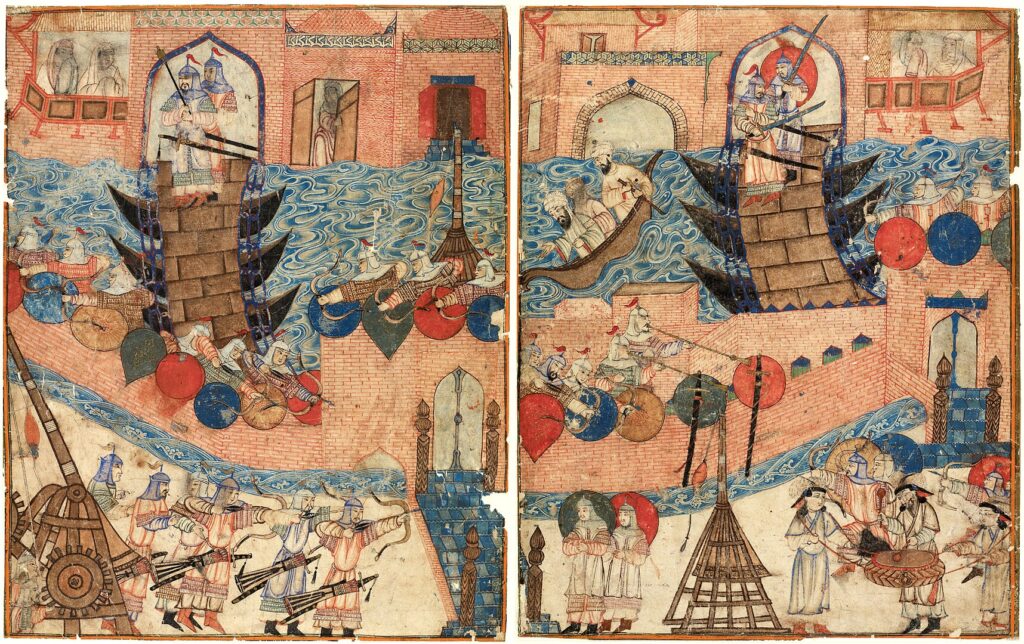

A 14th century depiction of the Siege of Baghdad, in which the Mongols decisively secured their hegemony over Mesopotamia

In 1330, he set out from Mecca again, this time travelling south to the port of Jeddah, and then, in small coastal boats, to Yemen and across the Red Sea to Somalia.

Battuta wrote one of the only descriptions available to us of medieval Mogadishu in Somalia, describing it as a large city with great wealth. After leaving Somalia, he headed south along the East Coast of Africa, where he would visit a number of the Swahili trading cities.

Battuta’s travels between 1325 and 1332

The furthest south he reached was the city of Kilwa in modern Tanzania, where he marvelled at its great mosque, after which he turned and headed back north to Oman and then back to Mecca.

In 1332, he decided he would seek employment in the Islamic kingdom of Delhi in India, and so set out for India. However, he wanted to take the overland route, which began in Anatolia, and so travelled to Egypt, crossed the Mediterranean on an Italian merchant ship and then made his way along the coast of modern-day Turkey. While in Turkey he purchased a number of Greek slaves − servants and concubines − to accompany him on his journey.

Evidently not content to head straight to India, Battuta travelled north to the lands of the Golden Horde in modern-day Ukraine. He spent some time with the Khan there and then travelled with the Kahn’s wife to her home city of Constantinople.

At the time, Constantinople was still ruled by the remnants of the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Entry of the Crusaders into Constantinople, by Eugène Delacroix, 1840

This meant that this was his first journey to a non-Islamic kingdom. While there he saw the magnificent Hagia Sophia and told Christian priests of Jerusalem which he had visited during his journeys to and from Egypt.

Tiring of Constantinople, he travelled back across the Black Sea to the steppe of southern Russia and from there set out for India over land. He crossed right over the steppe of central Asia and visited many cities along the Silk Road, noting the enduring damage from the Mongol conquests of over a century before.

Crossing the mountains from Afghanistan to India, he had this to say:

“After this I proceeded to the city of Barwan, in the road to which is a high mountain, covered with snow and exceedingly cold; they call it the Hindu Kush, that is Hindu-slayer, because most of the slaves brought thither from India die on account of the intenseness of the cold.”

In 1333 he reached the Indus River in modern-day Pakistan.

He would come to work for the Sultan of Delhi, but his new employer proved a difficult boss. At times he was hailed as a trusted confidant, and at others the sultan accused him of treason and threatened to kill him. Nervous for his life, Battuta tried to get permission for another hajj to Mecca, but was denied. In 1341 however, he finally got a chance to escape by being tasked with travelling as an emissary to the Mongol-ruled Chinese Empire.

As he set out of India, he was robbed, kidnapped and nearly killed, but eventually managed to get back to the expedition with whom he travelled along the coasts of India. On this journey, his ship was sunk in port during a storm. A second ship, which survived, sailed without him.

Afraid of being killed by his employer for failure he hid in the court of a southern Indian king. When his protector was overthrown, he fled to the Maldives where he worked as an Islamic judge for a time.

There he annoyed the locals with his strict enforcement of Islamic law, and so he decided to move on before he could be fired.

He travelled to Sri Lanka, then set out again for China, travelling via the sultanates of Indonesia and Malaysia, and a detour to the Hindu empire of Majapahit in Java.

The route Battuta followed between 1332 and 1347

He finally reached China in 1345. Among his observations was that local artists made excellent portraits of arriving foreigners, which were used as security identification.

He spent some time travelling between China’s cities, and even met the Mongol Chinese Emperor. Finally, he decided to head back towards Morocco, though lost most of his money when he was ripped off by a ship’s crew.

In 1348 he regained Damacus in Syria. It was here that he learned that his father had died 15 years earlier. Battuta was held up for a time in Syria – this was just when the bubonic plague hit the Middle East, on its way to Europe. After the plague passed, he would continue his homeward journey, describing the horrific devastation left by the plague.

Battuta decided to make one more hajj to Mecca before finally returning to his home. He arrived in 1349, just after his mother’s death.

With his parents both dead, he decided to leave again, this time for Spain, and the Islamic-controlled lands in southern Spain. He didn’t stay long, as threats of invasion by the Christian king of Spain prompted him to leave.

The final trek, from 1349 to 1354

In 1352, he set out across the Sahara, finally reaching the salt mining towns of northern Mali, and, later, the capital of the Mali empire. Here, he remarked disapprovingly on how much the women exposed themselves, which he felt was not befitting of a Muslim kingdom.

Battuta would end his journey with visits to Timbuktu and Gao, important trade centres, before being ordered home by the Sultan of Morocco.

While in the court of Morocco, he recounted his travels to a scholar named Ibn Juzayy, from whom we get the only account of his travels. Juzayy titled the work describing the journeys as A Masterpiece to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling.

An 1860 copy of selections from Battuta’s account

This account by Juzayy has its problems. It doesn’t make clear which were Battuta’s observations and which were from other sources. It was also dictated to Juzayy by Battuta, entirely from memory, as he kept no notes on his travels. As such, many details might be mixed up or invented. Some modern scholars believe he embellished his journey with the gossip and hearsay he heard during his travels, prompting him to include places he never visited. There is even some debate as to whether he visited China at all, as his stories are similar to other medieval accounts of visits to China and may have been partly plagiarised.

Purported mausoleum of Ibn Battuta in Tangier [Boubloub, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=128113388]

Battuta died in 1369 after spending the remainder of his life working as a judge in Morocco.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend