This rallying cry of countless popular movements against oppression is too often burdened with the irony of its succeeding in achieving the reverse: liberation seldom translates into liberty.

Many who rally behind the demonstrations and struggles of unfree people in fact harbour a contradictory suspicion of the idea of letting people freely choose for themselves.

In South Africa, this has proved tragically true over the 25-year – post-liberation – period. The condition is even more pronounced today in the commitment of the ruling African National Congress to such policies as expropriation without compensation, National Health Insurance, transformation by race-based edict and the minimum wage, all measures that reduce rather than enhance liberty, yet are crafted in the name of ‘liberation’.

By contrast, the truly liberating agency available to South Africans is their own choices, if only they’d be allowed to make them – and, importantly, if mechanisms to help them were used in place of the policies which, thus far, have done far too little .

This is a view that is gaining wider acceptance today. The most recent acknowledgement of the failure of BEE – reflected in a separate Daily Friend report today – comes from Capitec chief executive officer Gerrie Fourie who said in an interview on 702: ‘If you look at BEE in totality in South Africa, it hasn’t worked because it should be there to help all South Africans and, unfortunately, it has only helped a couple of people. I think that is something we need to work on.’

He added: ‘There is also an attitude in South Africa that we need to work on that says ‘what can I do?’ rather than (focusing on) entitlement. I think that’s quite crucial for our culture going forward.’

That simple question, ‘What can I do?’ places the emphasis of social and economic change on the agency of individuals, and the scope of their freedom to make choices that better match their needs and ambitions.

On a flight to Johannesburg a few years ago, this writer saw a brief glimpse of the landscape on a banking turn which offered a visual image for the distinction between an imposed way of doing things and a freely chosen one.

Far below, the unmistakable geometry of peri-urban settlement registered as a neat patchwork of lines and squares, of dusty fields and ruler-straight roads cleanly intersecting at junctions and nodes of habitation.

But this landscape that had been brought to order and made useful by a plan with the stamp of authority was subverted by the evidence – a tracery of footpaths, defiantly at odds with the regular geometry – of people making their own choices. The paths cut corners, snaked across open ground, converged on junctions of their own, revealing people’s daily choices in determining the most efficient and convenient ways to get around in the least time, with the least effort.

Free choice is a powerful force which, on its own, may seem guaranteed to produce anarchy. But that is no argument against its virtues. Harnessed effectively, as political freedom is in democracy, or economic freedom is in the marketplace, it brings dynamism to society because it at once stimulates and provides an outlet for that question, ‘What can I do?’

And how it could work is spelled out in a comprehensive alternative to the race-based empowerment that has been failing South Africans since 1994. This alternative was proposed by my colleague, IRR head of policy research Dr Anthea Jeffery.

Called Economic Empowerment for the Disadvantaged (EED), it dispenses with race as a beneficiary qualification and demonstrates how it is possible to harness the agency of individuals, the real ‘power of the people’.

Jeffery writes: ‘This would include an alternative EED scorecard that incentivises and rewards investment, employment, innovation, the expansion of the tax base, and rapid economic growth.

‘EED would also reach down to the poor by providing them with tax-funded vouchers they could use to buy the schooling, housing, and healthcare of their choice. Schools and other entities would then have to compete for their custom, which would help to keep costs down and push quality up.’

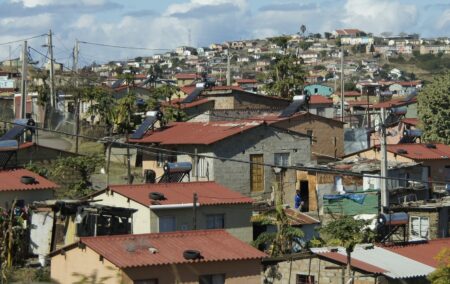

In a rapidly urbanising society – in which 65% of the population already lives in cities – a perennial challenge is housing, both for the newly urbanised, and for the millions whose housing needs were, as a matter of policy, never properly acknowledged or met under apartheid.

One of the boasts of the post-1994 period is that the government has provided some three million ‘free’ RDP (Reconstruction and Development Programme) houses and roughly one million serviced sites.

Yet, as Jeffery points out, over this period, ‘the housing backlog has nevertheless increased from 1.5 million to 2.3 million units, while the number of informal settlements has gone up from 300 to 2 225, an increase of 650%’.

At the same time, the housing subsidy has shot up from R12 500 per household to some R160 500 today, at which amount it was pegged in 2014. ‘Yet despite this massive increase, the quality of the houses being delivered is often very poor. In addition, the pace of delivery has slowed to the point where it will take at least 20 years to provide homes for all those on the national waiting list, let alone meet new demand.’

EED offers a sensible, achievable alternative. Let’s look at the detail of the EED approach. (A focus on solutions is exactly what is missing from most emotionally charged debates about race and ‘transformation’.)

Jeffery writes: ‘Housing policy needs a fundamental rethink to empower individuals, provide better value for money, and break the delivery logjam.’

As her report on EED argues, housing vouchers provide a way of achieving these key goals. These vouchers would be redeemable solely for housing-related purchases – and would go to some 10 million South Africans between the ages of 25 and 35, who earn below a ceiling of, say, R15 000 a month.

‘The voucher would be worth, say, R800 a month, or R9 600 a year, and each recipient would continue to receive this voucher for ten years. Each beneficiary would thus receive close on R100 000 over this period.

‘A couple would be able to pool their money and would thus receive nearly R200 000 over a decade.

This amount could be topped up by their own earnings, which means a couple earning R5 000 a month could devote R1 000 of that to housing. Over ten years, this additional amount would boost their housing budget to close on R320 000. Such sums would help substantially in empowering people to build or improve their own homes, or obtain and pay down mortgage bonds.

‘The cost to the fiscus for 10 million beneficiaries would be R96bn a year, and again this could be met by redirecting much of the current budget for housing and related community development. The voucher system would be much more effective in stimulating housing supply as each individual who receives a voucher will have a personal interest in ensuring its optimal use.’

Moreover, ‘whereas current policy adds to housing demand by encouraging existing households to split up – so that each new household can qualify for a “free” house – the new vouchers would remove this perverse incentive’.

The EED voucher system and the market it would create would encourage the private sector to build many more houses and/or apartment blocks, or to revamp many more existing structures for housing purposes.

‘Beneficiaries would also find it easier to gain mortgage finance, which would further stimulate new housing developments. Beneficiaries who already own their homes would be able to use their housing vouchers to extend or otherwise improve them.

‘Some might choose to use their vouchers to build backyard flats, which they could then rent out to tenants also armed with housing vouchers and so able to afford a reasonable rental. This too would help increase the rental stock available.’

People currently living in informal settlements ‘would increasingly have other housing options available to them. Some would move into the new housing complexes and others into new backyard or other flats’.

This would mean informal settlements would become less crowded, making upgrading easier.

‘Those who choose to remain in them would be able to use their housing vouchers to buy building supplies, hire electricians, plumbers, and other artisans, contribute their own labour or “sweat equity” to reduce costs, and gradually upgrade their homes.’

With an EED voucher system, ‘households would be empowered to start meeting their own housing needs, instead of having to wait endlessly on the state to supply them with a small, and probably defective, RDP home’.

‘Individual initiative and self-reliance would expand. The enormous pent-up demand for housing would diminish. With title deeds to homes also made available (as an essential complementary reform), a more normal housing market would develop. Accelerated housing delivery via the voucher system would also stimulate investment, generate jobs, and give the weak economy a vital boost.’

Almost all the attention in the debate about delivering a better life dwells on race and pointless disputes about who deserves a gold star (only those who toe the line – at the expense of the poor, it should be noted). For as long as this happens, South Africans’ long-deferred liberation is only deferred again.

The strongest counter-argument is also the simplest: give power to the people.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.