Francis Fukuyama is the most internationally renowned political theorist to speak in South Africa in 2019. Though his lecture was widely overlooked, the argument he made was simple. Before getting lost in the Cold War debate of Left versus Right, remember to check out the country you are in, in particular. Whatever the foreign distractions, the question must be: so what does any of this mean to us in South Africa?

When I was a university student, I often encountered high school students who would ask, ‘What’s the best university?’ Usually I was part of a group of American students who would predictably toot their own university’s horn. ‘Harvard!’ some would shout. ‘Harvard’s got the biggest endowment and most Nobel prize winners!’ ‘No, Columbia!’ others would counter. ‘It’s in the world’s most dynamic city and Barack Obama went there!’ For others, again, it was MIT … ‘Its engineering is unparalleled and you don’t have to deal with so much virulent student politics!’ Ugh. I’d hear the same sort of thing in SA, too, about Wits, UCT, Stellies, Rhodes, Tuks and so on. It would grate my teeth then, too.

My view was, and remains, that the only decent response is to ask: ‘What do you want out of university and what are you prepared to put into it?’ I know it is less exciting than the usual hurrah! of championing one’s own alma mater, but if people really want to know how to think about this significant question, the only true answer is: there is no best university. Categorically. No such thing exists. There is only what would be best for you, based on your individual case. And that’s if university is even the best thing for a youngster at all – one of my roommates made the right decision to drop out of Princeton and become a happy, wholesome plumber.

I visited Wits this year for a lecture by Francis Fukuyama, the man who correctly predicted the end of the Cold War and incorrectly ‘predicted’ the End of History, this being the title of the book that made him world famous. In Joburg this year, he applied the same argument I make about universities to countries and their economies; there is no such thing as the best economic model. There is only the question of what is best for this country, now, in particular.

Since at least as far back as the 1950s, politico-economic analysts have been eager to find some ideal size of government that fits every country equally. Slogans and chants (and guns and bombs) established two rhetorical extremes, of total state control versus the free market. ‘The Soviet bloc’ versus ‘the West’.

Between those extremes, each analyst could find his or her own favourite point on the spectrum to champion as the best. But Fukuyama pleaded with us to get over the reductive one-dimensional approach and begin, instead, with a more particular question about what capacity does your state have now?

On the old one-dimensional view, all that matters is how much you think the government should intervene, which can roughly be measured as state spending as a portion of GDP. So, for example, state spending makes up more than 50% of GDP in France, Finland and Denmark.

But before you get trapped into thinking one size fits all, look at Greece, in which government spending is also more than 50% of GDP, but where living standards are far lower, where state capacity is weak and where economic stagnation and repeated government bankruptcies have produced both social and economic turmoil.

On the other hand, look at the Republic of Ireland, where state spending is below 30% of GDP according to OECD data, and which has, largely through private thrust, become one of the most bountiful, peaceful countries in Europe. This despite its lagging start. Ireland suffered one of the nastier histories of colonialism, a population-halving famine and mass sectarian terrorism in living memory. Yet, now, its GDP per capita is about R1.1 million and its unemployment is at 5%.

Doesn’t it just make simple, common sense to conclude that there is going to be a different ‘sweet spot’ for different countries at different times?

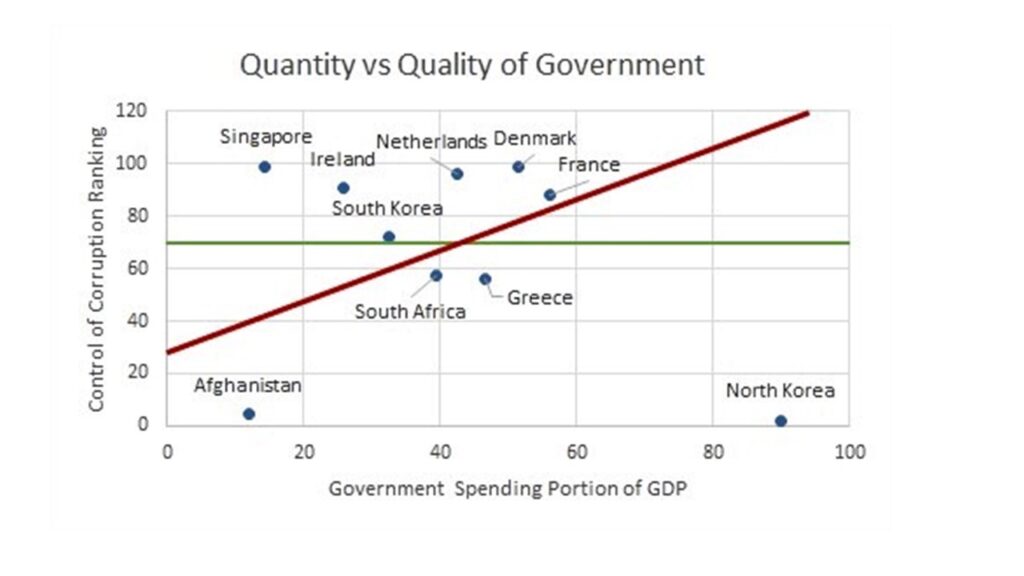

Fukuyama thinks you have to look at the quantity of government intervention and the quality of government in the same picture. I have made a mock-up of Fukuyama’s picture above to illustrate his basic points. One is that (see the green line) there are rich countries with big governments and rich countries with small governments, but there are no rich countries with governments that are nearly as corrupt as ours is, as measured by the World Bank.

Another basic point is that if a particular government has very poor capacity then its role should likewise be very limited. Overburdening itself will generate perverse incentives, rent extraction, outright bribery and opportunistic ostracism of politically vulnerable groups so that the state can excuse its own failures. An already clean government can intervene in the market effectively, fine-tuning outcomes in education, health, wealth and the environment – but only once it has got the basics right.

Thus, Fukuyama drew a diagonal line (see the red line) across his two-dimensional graph, suggesting that before you calculate whether your own government should expand or contract you should first check how corrupt it is.

In South Africa, the problem is that outside the Reserve Bank and the Treasury almost everything the state touches has turned to muck. Our public education system is one of the ‘world’s worst’, bang for buck, according to the Economist, while the percentage of students who enter it and leave with a pass in maths is in the single digits. Our public healthcare system has produced the Life Esidimeni catastrophe, and daily tragedies. Umpteen state-owned enterprises (SOEs), from Eskom, SAA and Transnet to SANRAL, Denel and the SABC, are in dire straits.

Worse, an estimated one third of GDP has been pilfered and, years down the line, no one is in jail. The police are the least trusted state institution in the country and, according to a poll by the Institute for Security Studies, half of South Africans think ‘all’ or ‘most’ of the police are involved in corruption.

It’s been election time (again) in the UK and plenty of SA’s elites have cheered for Jeremy Corbyn over Boris Johnson on the basis that the former would grow the government to the right universal ‘sweet spot’. The question remains, what about us? Our state’s capacity is so moribund that even universalist devotees of the Left should recognize that here the state must shrink and develop competence in its core capacities first.

Put another way, just because the United Arab Emirates are doing well with their airline, Emirates, does not mean that SAA is something we South Africanscan afford to keep, for the very simple reason that SA and the UAE are different countries, with different state capacities.

So, given our state’s weakness, privatize as much as we can immediately, right? Wrong.

When the Berlin Wall fell, Fukuyama noted: ‘American economists and the international financial institutions were urging rapid privatization in countries that did not have the state capacity to do an auction of public assets fairly. So what happens is that those assets are bought by insiders that have special knowledge, it’s a case of asymmetric information, they take advantage of that special knowledge, they end up with the public assets and that’s why to this day you have a class of oligarchs in those countries.’

The result was the fiscal rape of Russia. Privatization after the collapse of the USSR remains likely the largest single theft in world history, as one of the world’s superpowers was robbed blind by a tiny network of state capturers, also known as oligarchs. According to Gabriel Zucman, more than 60% of Russian financial wealth remains hidden offshore after more than half of it was stolen and GDP was cut in half during the rapid privatization – the kind of catastrophe that makes our ‘lost decade’ under the Zuptas look like a wee hiccup.

How do we stop the fiscal rape of Russia being repeated here? Surely that should be the foremost question among the South African Left, the self-proclaimed enemies of oligarchs?

Privatization comes in two phases: in the first, the decision to privatize is made and in the second the sale is offered, checked and concluded. The second phase must take place under deep scrutiny, especially from the media and independent observers, lest the same greedy private-sector extractors siphon off vast super economic profits.

But the overall time for both phases 1 and 2 of the privatization process is limited by our ability to keep bailing out the sinking ships in the meanwhile. Finance Minister Tito Mboweni has warned that our national debt will climb to unmanageable heights at above 70% of GDP in the next three years, which, given the cost of borrowing – for us, in particular – is beyond manageable.

We could use the vanishingly limited time available to continue debating whether or not to privatize Eskom, SAA, and the state-owned land at least 17 million South Africans will sleep on tonight. Or we could increase the amount of land the state owns, ignoring the fact that the Department of Land Reform and Rural Development is so corrupt that the Constitutional Court ordered a ‘special master’ to basically take over the ministry. We could increase the size and bailouts going to SOEs, ignoring the fact that this will lead, as sure as night follows day, to the bankruptcy of South Africa.

Or we get through phase 1, and then reach the hard part; privatization that is sufficiently scrutinized that we do not fall into Russia’s trap of the 1990s. Which road has Ramaphosa’s administration set us on as we emerge from the Christmas break? The answer is: more land to go into state hands under ‘nil’ compensation, and further pledges to rent-extracting SOEs.

Not only do some of our elites physically live in Scandinavian paradise (remember Zindzi Mandela tweeting from Denmark that she was not accountable to South African citizens who happen to be white), but our policy makers seem to have their heads in Danish clouds, too. And that is no place from which to manage the reforms that will come, one way, or the wrong way.

See the most globally notable analyst’s SA speech of 2019 here.

[Picture: Fronteiras do Pensamento, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50628567]

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.