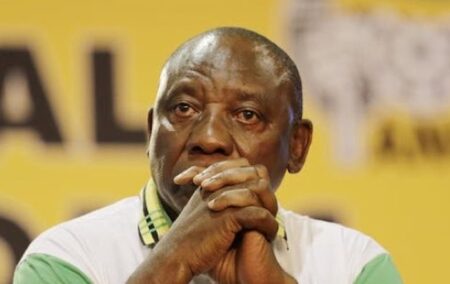

It’s taken about two years for the captains of industry to recognise something that less-powerful and less-connected people have known for a good while – Cyril Ramaphosa is not a leader. He is certainly not leading us to become a prosperous country courtesy of a vibrant market economy.

But how can this be? Big business hailed him as a pragmatist, a businessman, a business leader. Ramaphosa understands what we need, they said. He will lead us out of this economic quagmire that he and his colleagues allowed to happen under Jacob Zuma. So how did we get it so wrong? Why have the impression he gave and the words he uttered not correlated with his actions?

Ramaphosa was one of the very few African National Congress (ANC) leaders to be deployed by the ANC to become a major beneficiary in empowerment deals. The purpose was to create wealth outside of the formal ANC structures. This was necessary in order “to create a funding loophole which could not be done within the ANC as the capitals (sic) raised were (sic) from within its own alliance. Secondly it ensured that the ANC would not need to rely on other companies to raise funds which could have become a risk if the private sector colluded against the ANC. Thirdly it would provide a mechanism for broad based ownership on the JSE and link private sector companies to the ANC.”

The deployees would gain access to substantial wealth, which would ensure that the said deployees would donate substantial amounts to the ANC in return.

In 1996 Ramaphosa resigned as secretary general of the ANC. The reason given at the time was that he fell out with Nelson Mandela for not being recognised as Mandela’s deputy president in place of Thabo Mbeki. According to an article in News24 of 13 July 2015, (here) this was a smoke screen.

Until his succession to the deputy presidency in 2013 Ramaphosa was a director (sometimes chairman) of at least Alexander Forbes, the Black Economic Empowerment Commission, Johnnic Holdings, KreditInform, Sasria, Vancut Diamond Works, Reserve Holdings, Millennium Consolidated Investments, the Shanduka Group, SABMiller, Capital Property Fund, Pan African Resources, Bidvest, Assore, Lonmin, Standard Bank, Commonwealth Business Council, Macsteel, Liberty Life, Mpact, Seacom, McDonald’s and Coca Cola.

Anecdotal accounts suggest that Ramaphosa did little on those boards. He often arrived at meetings late, his board pack was often unopened and thus not read, and he never made a firm decision, always voting with the majority.

There is nothing to suggest that he absorbed the skills of business leadership; he didn’t have to. Ramaphosa is very charming and sociable and appears to have applied those traits well.

The arch-capitalist business magazine Forbes noted, without comment, that “Although, Ramaphosa is not a member of the South African Communist Party (SACP), Ramaphosa has claimed that he is a committed socialist. Ramaphosa has never referred to himself as a free marketeer or capitalist. Ramaphosa has noted more than once that he is a committed socialist.”

And that is what he has always said. He has never said that he was a capitalist or free marketeer.

During his business career Ramaphosa became extremely rich. As at July 2019 Forbes estimated his net worth at over R6,4 billion. Some suggest it’s closer to R8 billion. He is listed as the 17th richest man in South Africa.

We shouldn’t be surprised that he isn’t what we thought he was.

Ramaphosa’s formative years were in black consciousness, anti-apartheid politics. He became a career trade unionist and on the instructions of the Council of Unions of South Africa (Cusa) helped found the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). Ramaphosa became the general secretary of NUM although he was never a rank-and-file union member; he was a law graduate.

Ramaphosa became disillusioned by the black consciousness movement, and the NUM became a union for all nationalities and races. Ramaphosa was involved in the founding of the ANC-aligned Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in 1985 and the NUM came over with him.

In August 1987 Ramaphosa and his colleagues led more than 300 000 black miners on a strike in both the gold and the coal industries. Unlike previous strikes, this one lasted for three weeks.

Whatever the merits of the demands for the improvement of working conditions, NUM demanded an astonishing 30% wage increase which it only dropped to 27% near the end of the strike. The strike ended on the amount the companies had offered the strikers from the outset: an increase of between 15% and 23.4%.

Nine miners were killed, 300 were wounded and more than 400 were arrested. Over 40,000 miners were dismissed. Losses of up to $225 million were incurred by the industries.

The strike was a watershed in industrial relations, but as Professor Eddie Webster, an industrial sociologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, said at the time, the union had learned the ultimate power that companies had to dismiss employees.

”It was a trial of strength in which it was obvious that the employers would come out on top. Anyone who thought otherwise was naive.’’

The skills that Ramaphosa learnt as a unionist and honed as a senior ANC official were those of mediation and negotiation. Hence, his reputation as a negotiator and consensus seeker became mistaken as leadership.

Ramaphosa is always seeking consensus. In this year’s Sona he said: “Achieving consensus and building social compacts is a not demonstration of weakness. It is the very essence of who we are.”

This is profoundly depressing because leading a country is not always about negotiations and agreement. It is about being able to take risks, taking tough decisions and doing so timeously. The hallmark of Ramaphosa’s presidency has been the absence of decisiveness and risk-taking.

The skills that may have served him in the first part of his career are not the skills this benighted country needs. Ramaphosa’s most deceptive trait has been to tell people what they want to hear – saying one thing to one audience, but the opposite to another. This can only end in tears.

If meaningless bromides were hard currency South Africa would have a very rosy balance- of-payments surplus. The SONA provided juicy examples:

“What we have achieved, we have achieved together.”

‘We have worked to forge compacts among South Africans to answer the many challenges before us.

“Through the Jobs Summit, we brought labour, business, government and communities together to find solutions to the unemployment crisis, and we continue to meet at the beginning of every month to remove blockages and drive interventions that will save and create jobs.”

“We have been building social compacts because it is through partnership and cooperation that we progress.”

“We have been deliberate in rebuilding institutions and removing impediments to investment.”

And so it goes. The clichés and reassurances mean nothing; they just annoy.

Does Ramaphosa really think that advancing the national democratic revolution towards a socialist utopia amounts to removing impediments to investment? Moody’s will tell us shortly.

Given his socialist ideology, he probably never meant to move the country forward through building a market economy. In any event, whether he did or not, it has certainly moved us to the left and the world will punish us for it.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1. Terms & Conditions Apply.