Inextricably bound to the Covid-19 health emergency is the economic emergency that it is exacerbating; to imagine them as two separate or competing priorities in a society like South Africa is deeply misguided. The pandemic and the measures taken to counter it threaten lives and livelihoods, and the country’s overall development trajectory. The consequences for livelihoods will likely be with us long after the health crisis has subsided.

Perhaps nowhere will this be as apparent as among South Africa’s small business community.

Recognition of the value of small business (or Small and Medium Enterprises, SMEs, as the common descriptor has it) is long-standing, and predates democracy. Encouraging entrepreneurship and small businesses was a memorable element of government policy in the 1980s, and was part of the African National Congress’s election manifesto in 1994, and in every development strategy since.

It is important to pause for a moment to understand this properly. SMEs are a particular, defined niche in the economy. They are formalised, value-adding and profit-oriented operations. They are businesses, not survival schemes. Under the right conditions, worldwide experience shows, they are formidable contributors to wealth, job creation and innovation – and some will parse success into becoming large businesses.

Dynamism

Yet the SME economy has failed to produce this sort of dynamism in South Africa – certainly neither the apartheid nor democratic governments ever matched rhetoric here with successful action. Research published in 2018 by the Small Business Institute and Small Business Project (SBP) found that there were only around 250 000 SMEs in South Africa, a number considerably lower than previously thought (a 2016 study had estimated the number at over 2 million). And as the lockdown ticks along, concern about the outsized impact on SMEs is mounting.

‘The full brunt of the lockdown is likely to be felt proportionately by the SME sector,’ says economist Azar Jammine. ‘In the formal SME group, this is where one is likely to see a high number of bankruptcies and insolvencies. In its Monetary Policy Review today, the Reserve Bank forecast an increase in the number of insolvencies to 1 600 as a result of prevailing events. Restaurants, travel agencies, small retailers other than those dealing in foodstuffs, and small-time commercial property owners, have seen the virtual disappearance of any revenue, temporarily at least. These businesses survive on generating sufficient cash flow to continue running operations, but that cash flow has suddenly dried up, leaving them to carry substantial fixed costs. Variable costs are being reduced by salary cuts or retrenchments, but one is likely to see many of them folding all the same.’

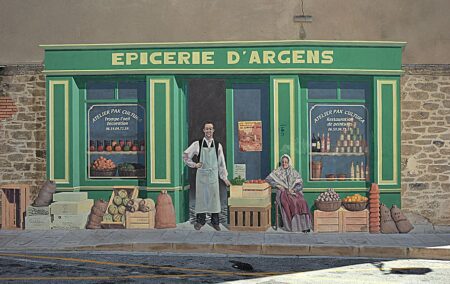

Behind each of these shopfronts, real or virtual, are stories of entrepreneurs and managers struggling with what for many is an existential crisis

Shadows of this are apparent to anyone who has ventured out to do ‘essential’ shopping: the shuttered fronts of beauty salons, electronics outlets, restaurants, picture framers, jewellers, fashion boutiques. Or, in its digital iteration, websites that announce services suspended until the lockdown is past. ‘See you then, South Africa.’

Behind each of these shopfronts, real or virtual, are stories of entrepreneurs and managers struggling with what for many is an existential crisis, for themselves and for the employees who depend on them – given the proximity with which small business owners work with their staff, this is often deeply personal and emotional. The IRR reached out to a number of SME operators to understand what the lockdown means for them.

The Covid-19 crisis hit South Africa on top of a decade of economic mismanagement, a contributor to the credit downgrade by Moody’s (ironically, on the very day that the lockdown began). This in turn came on top of, and alongside, policies and a business environment that had steadily upped the costs and difficulty of running a small business – labour market legislation, red tape, crime, power outages, governance incapacities as well as the burden of race-based empowerment policy and its implications for access to value chains.

Malaise

The SBP’s SME Growth Index – produced for several years from 2011, and still an excellent and revealing resource – recorded the frustration, year after year, of small business people at the growing difficulty of running their firms in South Africa. A crisis on top of a crises, compounded by a crisis, within a malaise.

‘The economic climate in SA before the pandemic made conditions tough to carve out a living making luxury items. Covid-19 and the downgrades are only going to compound issues,’ comments John Stedman, a manufacturing jeweller in Durban. Others expressed similar sentiments.

For the most part, though, there was understanding and in-principle support for the lockdown as an emergency measure (although one owner said that it failed to take into account the dynamics of South African society, and others questioned how it was being implemented). But this does not detract from the seriousness of its impact.

Dickon Jayes, director of media distribution firm iSizwe Distributors, comments: ‘The cost was going to be huge either way. Maybe by not locking down you would defer the economic impact but dead people don’t buy products and services and we would have had a lot of dead people on our hands. The cost to public and private infrastructure would also have been huge. So, either you try and limit the human cost in lives and take a big economic blow, or you take the human cost in lost lives up front and simply defer a comparable economic blow as a result of the lost lives anyway. There are no good or easy answers here….’

For iSizwe, the lockdown has not ceased all work, since its activities fall within the ambit of ‘essential services’. But it has taken its toll, as some titles are not being printed. Retailers other than supermarkets have been closed, cutting off an important avenue of business. Importing and exporting publications – a large part of the firm’s operations – is not possible.

Hit more directly

Those not deemed essential have been hit more directly. Sharing Jayes’ concern about the closure of cross-border trade is Ian Ross, managing director of Flora Export, which – as its name indicates – imports and exports flowers. It’s not only an issue for them, but for the whole value chain. ‘All horticultural activities in the country have had to be put on hold,’ he remarks, ‘As the largest importer of fresh cut flowers into the country, all imports from Kenya, Zimbabwe and Zambia have stopped. Not only are we as traders affected, but farms are now throwing flowers away on the farms, which means no income for them until this comes to an end. Effectively our customers (wholesalers, retail packhouses, florists, etc) are not able to trade. The largest and only flower auction on the African continent has also been forced to close. Flowers produced within SA for the export market are not able to be harvested, and as long as they can’t harvest and export, there is no income for those farms.’

Another business owner, in the home and office décor space, but who declined to be identified, said that as suppliers had had to suspend operations, and as their staff could not interact with their customers – installations and on-site consultations were not possible – his firm’s operations had ground to a halt.

Likewise, the proprietor of a furniture factory (who also requested anonymity) said that the lockdown had been a comprehensive blow. The firm was not able to open and, besides, orders had dried up: ‘All our clients have informed us that all outstanding orders are cancelled until further notice and that payments due will also be broken down into instalments due to their own retail commitments (rental contracts for shops, salaries). We are not operating at all and cannot generate cash flow.’

The lockdown has effectively killed the hospitality industry for the moment

Josef Martin, owner of Dabmar, an engineering firm based in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, told us that around 80% of the firm’s operations had been stopped, although their maintenance contracts with various coal mines were ongoing.

The lockdown has effectively killed the hospitality industry for the moment. Irene Jayes, who happens to be Dickon’s wife (an entrepreneurial couple!), runs a small but busy guesthouse, which is at times booked out for weeks on end. ‘The market has pretty much disappeared overnight,’ she tells us. Every booking has been cancelled, all deposits refunded, and no new bookings made as no one has any idea as to when travel will resume.

As much as possible, those SMEs unable to work as normal are trying to take their operations online, hoping to keep some semblance of business going. For some, this ‘home office’ strategy is merely a continuation of a cost-saving and convenience measure which they had adopted as a part of their ordinary business routine. For others, it represents a major adjustment, and a highly disruptive one.

Not negotiable

Manufacturing firms, for example, are unable to function off their premises. Some quoting and designing may be possible, but not much besides. Contact with clients is sometimes not negotiable.

Kirsten Beaumont, who runs a small swimming school in the midlands of KwaZulu-Natal, remarks: ‘I cannot teach swimming remotely.’

Even where the primary functions of firms lend themselves to remote operations – consultancy or advisory services, for example – the general contraction of societal activities is taking its toll. Marius Viljoen, whose Centurion law practice has shared his home premises for some 20 years, reports that the lockdown has nevertheless greatly limited his work. New work is not coming in, and although he offers remote and online consultations, this can be more burdensome than a face-to-face consultation. ‘It takes a large number of emails to convey the same message that could be done in a half-hour consultation,’ he says.

Michael Browning, managing director of TMJ Attorneys, with offices in Pietermaritzburg, Durban and Johannesburg, adds that while some of the firm’s clients now insist on remote consultations, and while the firm has the IT infrastructure to support it, there are nevertheless some instances in which contact is essential. They cannot, for example, access the courts or do registrations at the Deeds Office, effectively halting these streams of their work.

Without exception, the businesspeople we spoke to intended trying to avoid retrenchments

As firms were taking damage from the lockdown, the implications of this on their employees was a universal concern. It’s perhaps something that we forget in a resentful political culture that bonds of concern can run deep among people who work closely together. Without exception, the businesspeople we spoke to intended trying to avoid retrenchments – ‘We will try everything in our power’ to do so, said one.

The sad reality, though, is that in a hard-pressed environment, there are few scenarios in which employees are not adversely affected. (Although this needs to be qualified by noting that small business owners will invariably have sacrificed their personal incomes first – those impressed by the cabinet taking a one third cut in pay should remember that many entrepreneurs are taking 100% cuts, and may be doing so for some time.) Some will not able to pay their staff while the lockdown is in operation and business activities in abeyance.

Browning says that although the nature of their work possibly makes them less vulnerable than many to the lockdown, they nonetheless remain very vulnerable. Keeping staff on is a priority, but one that needs to be understood in terms of the harsh environment: ‘We have always done what we can to preserve jobs and avoid the retrenchment route; but there are many uncertainties ahead including the income we can expect to receive over the closure period and the extent of the closure period. But yes, we may face that reality.’

Grimmer reality

An even grimmer reality is the threat to firms’ very existence. Most of those we spoke to shared this fear. One said that company reserves would carry their payroll (with some 90% of staff being unable to work) until the end of April – that would be ‘D-Day’. This appears to be a common point at which the Covid-19 crisis could turn from dangerous to deadly. As it happens, this coincides with the extended lockdown deadline.

Those that could had done what was possible to restructure their own payments to their creditors – the cash crunch on SMEs works both ways. ‘This is causing ripple effects throughout the economy,’ one told us. ‘When our customers don’t pay us, we can’t pay our creditors, who can’t pay their creditors, and so on.’ Until trade is happening again, this cycle is vicious and will be self-reinforcing.

Indeed, most of those we spoke to – all of them competent, confident business people, skilled and knowledgeable in their fields – perceived a threat to their firms’ survival. ‘Unprecedented’, as one put it.

Frighteningly, this seems to be representative of the general picture in the SME economy. Inquiries by sme.africa and Sasfin found that 62% of SMEs sampled saw the Covid-19 pandemic as having a ‘big impact and threat to the existence of my business’ – along with 4% who had already closed down, and 33% that saw its impact as manageable ‘at this stage’.

Relief measures announced by government and the private sector offer some hope, although it’s unlikely that they will match the scale of need – especially as the lockdown will see firms losing out on over a month of activity (assuming it is not extended again), with all the damage to the economy this will bring with it.

Not a grant

These have their limitations. Reports indicate, for example, that applications for assistance from the Sukuma programme set up by Johan Rupert rapidly exceeded its capital. The South Africa Future Trust – the Oppenheimers’ vehicle to extend support to distressed firms so that they can continue to pay their employees – offers a no-interest loan, not a grant. It also does not allow disbursed payments to be made to family members, even though small firms frequently legitimately employ family members.

Ron Weissenberg, an entrepreneur in the minerals space, says: ‘The operative word is “relief” – payment holidays, for example, are not relief; they simply reschedule the debt and/or accumulate more interest. The current measures announced by the state are supply-side incentives and more of an indication of ignorance in the way businesses function than a help. Delaying the payment of provisional tax for instance, assumes one has made a profit. An example of what businesses need is cash now to cover fixed costs.’

Nevertheless, most of the SMEs we spoke to have either applied or were investigating doing so. There is a collective holding of breath…

The sudden shift to remote and online work has been a major boost for firms that operated in this way before the crisis

While the weight of opinion was pessimistic, a couple of SMEs saw opportunities in the crisis. The sudden shift to remote and online work has been a major boost for firms that operated in this way before the crisis. Gita Lowe from Performability – a human resources, recruitment and training outfit – told us that, as she and her team had long operated remotely, it was largely business as usual, albeit with some glitches as a result of connectivity issues. Capturing fingerprints and running police clearances had also been circumscribed. But the online recruitment offering was enormously attractive to clients in a time of isolation.

The sale of medical and hygiene products, naturally, has been given a major boost. Monica Ross (no relation to Ian) of Neolife, says that the lockdown has ‘rocketed my business into the heavens’, especially since it has been possible to do marketing and conduct webinars online.

Perhaps they point to a new mode of working that technology will make increasingly attractive, and whose adoption the pandemic has accelerated.

Nevertheless, for most, things look bleak, and the full possibilities offered by innovation belong to the future.

Rehabilitation

The health crisis will end – when, we do not know – after which the SME economy will need to look to its rehabilitation.

It goes without saying that, for the SMEs we approached, getting business moving again was the number one priority. As interim measures, they hoped that some financial support would be forthcoming, in the form of grants or low-interest loans or even in direct support to the population to start to generate demand. As one bluntly phrased it: ‘The government will have to pump massive amounts of liquidity into the markets, deficit be damned. I don’t see any other way.’

Promises by President Ramaphosa that government will provide enhanced support for the economy (‘additional extraordinary measures’) will be watched closely, although given South Africa’s tenuous fiscal position, excessive optimism is to be avoided.

Others saw the crisis as underlining the imperative to buy local, to keep the rand circulating in South Africa and to prop up local economies. ‘There is no better time than now for South Africans to support locally produced goods rather than cheap imports from the East,’ says John Stedman. (For those in tourism, the collapse of the rand may well divert much of the remaining South African tourism spend their way.)

Policy backwater

The Covid-19 crisis should not conceal the fact that the problems besetting SMEs have been with us for decades. Bernard Swanepoel of the Small Business Institute recently wrote a piece entitled appropriately, ‘Oh, so now you care about small business?’ SMEs have in practical terms been a policy backwater, and subject to the domination of what Azar Jammine calls the ‘golden triangle’ of government, unions and big business.

Jammine continues: ‘Much will depend on how seriously the government treats the potential demise of SMEs. One fears that because of the power of big business in South Africa, there will be an attempt by government at working with the big business sector to find solutions to the country’s problems. Many of these will be directed at informal businesses in township areas and rural areas rather than trying to rescue established SMEs who are in difficulty. Many of the latter are drawn from the white community and as such might be seen as expendable even though they account for a substantial proportion of formal sector employment.’

And perhaps this is the defining point. If government’s plan is merely to return to the status quo ante – the mix of racial ‘empowerment’ (being ‘very hard’ on employers who fail to live up to political expectations), patronage, and politicised and often dysfunctional administration, while declaiming the construction of a ‘developmental state’ – it has learned nothing. And nothing should be expected from this, save the accelerated decline of the SME economy and the potential it represents.

NDR ideologies

As Ron Weissenberg put it: ‘Far worse than the effects of Covid-19 are the effects of three decades of social engineering and poor, almost regressive state policy. Prior to Covid-19, most businesses were going off-track, the economy was in recession and government consistently ignored the measures necessary to create an enabling economic environment, and stimulate confidence and economic activity. If we emerge from Covid-19 fully restored to the prior position, the NDR ideologies, disinvestment and lack of policy certainty will remain – and the kind of effort needed to kick-start the economy just won’t happen in South Africa.’

The decision of the Department of Tourism to apportion its relief on BEE – racial – grounds suggests that the same destructive ideological impulses are at play even in the midst of an emergency. It portends poorly for the future.

When the lockdown is over, and South Africa returns to its shopping centres and strip malls in the months that follow, the full impact of this is likely to become apparent. Those shuttered shopfronts may well be permanently closed.

Unless we see a fundamental course correction – not just relief or support, but a willingness to revise the business environment – this could be the swansong for South Africa’s SME aspirations. This would in itself be sad. Tragic, however, is that many of our policymakers seem to be indifferent to it.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend