The President’s most consistently repeated claim is that the lockdown “delayed the spread” of Covid-19 as intended. No evidence has been produced to test that claim against the closest viable alternative. If we do not face facts now it will be too late to respond to the rising wave in a reasonable way once the infection rate peaks.

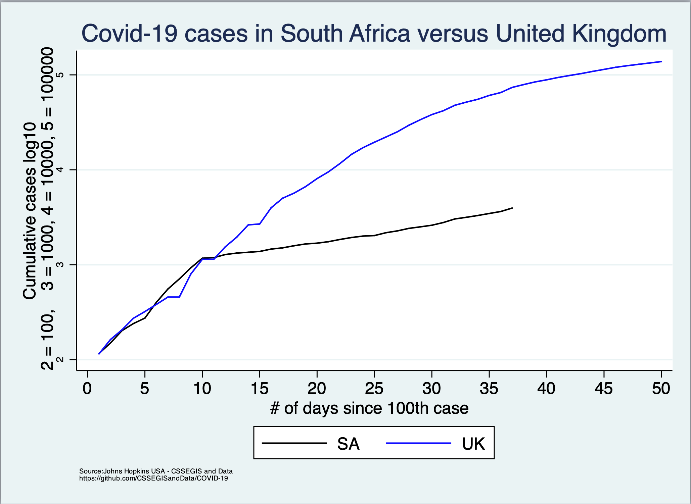

Look at the graph below, for it tells you what you need to know about South Africa’s response to Covid-19. It was published on April 27 on the Daily Maverick by arguably the country’s most famous data scientist, trained doctor and former Vice Chancellor of UCT Max Price, and then republished in the London Sunday Times.

Price’s graph clearly shows a reduction in the rate of new cases in South Africa, starting just to the left of figure 11 on the horizontal axis, which corresponds to March 27, day one of the brutal economic lockdown. The lockdown could not have had such an immediate effect, as Price knows. What then caused the “kink” above?

Eleven days before the case-load kinks, South Africa entered a “Call Up” scenario marked by Ramaphosa’s stirring “State of Disaster” declaration on March 15. Explaining the graph above, Price said the “sudden decline in new cases” was “most likely due to the declaration of a ‘State of Disaster’”, i.e. Call Up. That is because one should expect approximately “10 days” delay before “significant impact on symptomatic infections”, Price explained.

The Call Up included light regulations, school closures, border closures, bans on large gatherings and public drinking after 6pm; but it left the heavy duty of saving lives and livelihoods in the hands of South Africans themselves. All political leaders echoed the non-partisan Call Up to klap Covid. As Ramaphosa said, this was the greatest “Thuma Mina” – call on me – moment of mass voluntarism in South Africa’s recent history.

Google mobility data indicate the effects of this Call Up. Workplace and retail visits dropped 20%, while transit station visits dropped nearly 40%. But the quality of “visits” is at least as important, with people around the country masking, scrubbing and social distancing; many taxis complied by dropping to 50% capacity and sanitizing; businesses began to refit production lines; it became increasingly normal to stand 1m apart in queues; and millions geared up to work together, physically apart.

Price claims that the effective reproductive, Re, dropped from Re = 3 to roughly Re = 1.3 somewhere around this time. That claim also fits Price’s graph above, showing a major kink 11 days after the Call Up, with no further kinks after that.

It seems that we have a clear-cut case, then, that the Call Up worked, but withthe lockdown adding nothing. Yet Ramaphosa keeps saying the opposite. Price and I should join hands and inform Ramaphosa together that his very own Call Up was potent, not to be overlooked by power-hungry acolytes who champion the lockdown.

The problem is I have no access to the president, and Price keeps congratulating the lockdown rather than the Call Up and has done so from the start. A few sentences after reproducing the original graph and explaining in effect that the “kink” could not have been due to the lockdown, he wrote thatthe “lockdown” was “probably the most significant factor” in curbing Covid-19 in SA. This is confusing to say the least.

I have some sympathy with Price’s apparent contradiction of his own graph. Having dug down into the data, I maintain that Price’s graph relies on erratic testing numbers in the relevant period.

Unlike Price, I do not think testing numbers spiked up to March 27 due to a concomitant rise in cases, since most of the tests (at least 96%) in this period came out negative. And, unlike Price, I do not think testing numbers dropped after March 27 as a result of new cases dropping, in part because of a report from one government official that the country simply started to run out of testing kits at the time.

Doubting Price’s graph, I used other means, including international academic studies and mobility data, to show nevertheless that the Call Up did work; while the brutal, bloody, deadly, irrational, and unscientifically regulated lockdown did not.

Price’s graph, in my view, shows when the curve started to flatten, but for all the wrong reasons. It is like the infamous broken clock that happens to show the right time of infectious delay, even though the underlying reliance on erratic testing data is faulty.

Not so, Price shot back on the Daily Friend. Here, Price disputes my interpretation, mostly by attributing “assumptions” and “assertions” to me that I never made. For example, I never argued that Price was “wilfully” misleading.

Suppose, however, that Price is right and I am wrong. Suppose his kink-graph has been reliable all along, and that the testing was reliable. We should agree on the key point: our Call Up curbed Covid-19 like nothing else in South Africa, before or since.

For that to happen Price would not only have to argue that his graph is reliable, but also rely on it to draw his own inferences. And yet this is exactly what he seems to fail to do.

Here is another example of Price controverting his own graphs. He says there can be “no disagreement that, after commencing lockdown, the growth has been exponential”, supporting my claim that Re has been greater than 1 at least since March 27.

Except that Price reproduces thegraph,below, that“disagrees” with this claim, as it indicates Re = 0.85 on 5 April, which, if true, would be the opposite of exponential growth.

To my mind, the Re = 0.85 on April 5 is not a real indicator that we were reversing Covid-19 growth at the time, especially since Google Mobility data indicates massive travel spikes as people rushed to stock up before the lockdown 10-12 days before April 5. To my mind April 5 is the least likely time of all to show a radical reduction in Re.

The misimpression in Price’s graph is, I say, created by an artificial drop in testing, our “Command Council” being the only one globally to lock down the country just in time to slow testing.

Against that Price says that is unjustified criticism, for he insists tests dropped through no form of maladministration but rather because new cases stopped showing up as quickly after lockdown.

But, to defend the government’s testing regime and his own graphs’ reliability, he is committed to the claim that Re really was 0.85 on April 5, which is contradicted flatly by his own claim that there can be “no disagreement, after commencing lockdown, the growth has been exponential”.

As a final twisted irony there is this. If you take Price’s line and ignore my complaints about erratic testing, ignore my complaints about the lockdown driving people into stock up crowds, and take his graph as reliable the upshot is this. The Call Up’s effect (with a “10 days” delay) on April 5 was to shrink viral growth down to Re = 0.85, after which the lockdown drove it up to Re = 1.3. If Price relied on his own graphs and assertions would he not have to conclude the lockdown made viral spread accelerate?

Misinformation from the top

I argue that Price has defended the indefensible, not just by his repeated affirmations of Ramaphosa’s claim that the lockdown worked, but also claims about how much it worked.

On May 13 Ramaphosa said we only had 12 000 confirmed cases and then he added a very dangerous claim; “without the lockdown and other measures we have taken, at least 80 000 South Africans could have been infected by now.’”

I criticized this misleading point (likely made because the president was misinformed), because on May 13 we probably already had 80 000 cases and possibly many more.

An epidemiologist who officially advises government told me that the number of infected persons was estimated to be between “6 and 16 times more” than the number of confirmed cases in South Africa at the time. On May 13 that means there were probably between 72 000 and 192 000 real “infected” persons, making nonsense of Ramaphosa’s claim that lockdown saved us from “80000 infected” South Africans.

Yet Price declared that “Ramaphosa was 100% correct to omit the reference to testing.”

Worst Case Scenario

On June 1 the country enters Level 3. Schools reopen at the same time as much of the economy. I believe this is a bad idea; reopening schools should be delayed until after the economy kicks back into gear (which should have happened months ago). In any event, mobility will suddenly rocket in a transport system having to crank up again after months of dormancy. And, after months of alcohol bans, there’s a risk of binges to boot.

The upshot is likely that Re briefly grows in real terms before settling back down to the Call Up norm, while images are widely shared to raise doubts about South Africa’s ability to curb Covid-19 without the army’s iron fist. The Unlock design sets itself up for apparent failure.

South Africa’s natural defences, a young population with possibly high natural immunity and low initial viral import, are overwhelmed. The wave of exponential growth that spread throughout lockdown continues to rise through June. A few hospitals are eventually overburdened and images beam across the world under the headline “SA is the new Italy”.

What do we do then?

On my analysis the lockdown did not work. Keep the Call Up, reinforce it through quarantining very specific hotspots if need be, and make every effort to trace contacts, heal the sick and relieve burdens. But you can be sure there will be another view.

This will be predicated on the untested conviction that the nationwide lockdown worked before and it will work again. This view will ignore the Call Up’s efficacy as stubbornly as Price ignores his own graphs. As the portion of tests coming out positive continues to rise it will become fashionable to always remind readers that tests underestimate true infection rates, which on current trends could easily exceed 1 000 000 in June.

Ramaphosa said we only had 12 000 cases in mid-May, “100%” affirmed by Price, so an estimated 1 000 000 cases talked of in June will give the impression that Covid-19 was under tight control until Level 3 let the virus rip.

Freedom is killing us, will come the cry. Who in our “Command Council” do you trust to resist the ensuing temptation? The boot of hard lockdown comes down on the nation’s face once more, driving millions deeper into poverty, putting unchecked power back into the hands of the Command Council that so many dare not criticise, and we will be expected to say thanks, you are saving us.

This is just a scenario in which the nation is misled by those who should know better.

The risk is that influential, but contradictory analysis – so long as it remains unreviewed – could play a role in guaranteeing a hard, cold winter for South Africans.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend

Image by Mylene2401 from Pixabay