Protea Lungi Ngidi caused something of a stir with a remark at a press conference in response to a question about race and the Black Lives Matter movement.

But where do South Africans stand on these issues?

The Institute of Race Relations (IRR) has been the leading authority on relations between South Africans for over 90 years. It is able to speak with significant insight on race relations given its long-standing commitment to building a free, non-racial, free South Africa, its history over almost a century of working alone and with others in fighting the injustice of racial discrimination, and its extensive data-led research over this long period.

About a year ago, our report, Race Relations in South Africa – Reasons For Hope: Unite the Middle, canvassed and analysed the attitudes of ordinary South Africans to matters of race, reconciliation, governance, and social challenges and justice. This report is the latest in a series based on polling by the IRR over many years, and is therefore not merely a snapshot analysis but part of the organisation’s continuing monitoring and analysis of race relations in South Africa.

The Reasons For Hope report confirms the long-standing and repeatedly vindicated position of the IRR that South Africans are moderate, decent people who share many ambitions, hopes and concerns across racial lines and fundamentally find common ground on matters too often portrayed as the source of deep and even dangerous division. One of these is the topic of race and sport.

Media storm

Published shortly after the media storm over alleged racism towards former Springbok rugby player Ashwin Willemse, the report noted:

‘We then explored further by asking people whether the selection of sports teams should be based strictly on merit or should put more emphasis on demographic representivity. Part of the background here was ex-Springbok rugby player Ashwin Willemse’s walkout from a live TV broadcast in May 2018. Willemse said he had been ‘labelled a quota player for a long time’ and was not ‘going to be patronised’ by his fellow rugby analysts, Nick Mallett and Naas Botha. An inquiry by Advocate Vincent Maleka found no evidence of racism, but recommended that the issue be referred to the HRC for a fi nal decision, as Willemse had declined to take part in his probe. The HRC announced its decision to hold a full and public inquiry into the incident in December 2018. In commenting on the Willemse case, sports minister Tokozile Xasa has stressed that national quotas remain vital. By contrast, Archbishop Desmond Tutu had earlier suggested that the focus should instead be placed on developing ‘adequate facilities’ in schools and clubs in township areas ‘to develop the talent’ there.

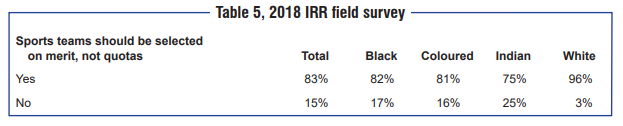

‘Against this background, respondents were asked whether South African sports teams should be selected ‘only on merit and ability and not by racial quotas’. Some 83% of all respondents – and 82% of black people – agreed that players should be chosen on merit, not quotas. Though support for this view was particularly pronounced among whites (96%), there was strong endorsement of it across all racial groups, as set out in [the table below].

‘Despite the minister’s support for racial quotas, the proportion of black respondents who reject this option is significantly greater now than it was in 2015 (74%) and 2016 (70%). This rejection of racial quotas in sport is also broadly shared across all racial groups – an outcome evident in IRR polls going back to 2015.’

Pursuit of national success

Lungi Ngidi is a great young cricketer of whom the country can be very proud. He embodies a continuing story of how things that once divided South Africans through state-imposed racism can now, and do, bring people together in pursuit of national success. There can be no quibbling with his saying in an interview that a stand must be taken against racism, but it must be remembered, especially during this time of great uncertainty and crisis, that sport has become for many an expression of the best of South African non-racialism. Where problems have arisen regarding race and sport in South Africa, they echo the age of state-imposed racial division and government-sponsored racial tension.

The challenge today is to confront such problems sensibly and honestly. Precisely because, as our data shows, South Africans want sport to be a symbol of non-racial unity and success, it is crucial to resist pressure from those who, under the guise of anti-racism, pursue ends starkly reminiscent of the racialism and division of the old days.

Very real danger

There is a very real danger that the Black Lives Matter movements falls within this ambit and so threatens South Africa’s strong and constructive race relations. That black lives matter is beyond question, but no-one must make the mistake of judging a movement by its moniker.

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, for example, is not democratic, does not empower or belong to the people, is more tyrannical monarchy than republic and does not cover the full Korean Peninsula.

If South Africans want to assert the admirable claim that the lives of black people really do matter, it will be necessary to confront the truth –tragically evident in the death of people like Collins Khosa – about the extent of government failures in protecting lives of the most vulnerable and socio-economically unempowered among us.

It would be a welcome development, for instance, were prominent South Africans, taking up Ngidi’s call, to step up and say the life of Collins Khosa mattered and the lives of unempowered, vulnerable people who remain deprived of liberty matter. Around this, all South Africans can rally.

Long-overdue justice

Just as important is to question whether the Black Lives Matter movement really does, in a sustainable way, advance the cause of long-overdue justice for people like Collins Khosa and, from almost a decade ago, Andries Tatane.

Life in South Africa, especially the lives of the poorest and most vulnerable, have become tragically cheap.

Ngidi is not wrong in his call for a stand against racism. But the unavoidable challenge for South Africans, the vast majority of whom live daily by the creditable standards of non-racialism, is to stand united against the genuine evil of too many lives not seeming to matter at all to those in the highest offices of state.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend