This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

25th July 306 – Constantine I is proclaimed Roman Emperor by his troops

During the 3rd century the Roman Empire went through a period of extreme crisis, with civil war, massive inflation and disease bringing the empire to its knees. In both west and east, some Roman provinces split away to form new empires and Rome seemed on the verge of losing its imperial grip. Collapse of the empire was averted when Emperor Aurelian defeated the separatists, though he himself was soon assassinated.

The crisis was finally ended soon after Aurelian’s death when Emperor Diocletian assumed the throne in 284. He ruled until 305, retiring to his palace on the Dalmatian coast, which still stands to this day. Diocletian finally stabilised the empire, embarking on a series of reforms aimed at solving inflation and resolving the civil wars that had plagued the empire for centuries.

He enacted a series of price controls to try to combat inflation, drawing up a list of all goods in the empire and setting maximum and minimum prices for everything. Disobeying this law resulted in execution. The policy failed, just as modern attempts at price controls do.

Diocletian’s most important reform was enacting the establishment of the ‘tetrarchy’. While much of this system is disputed by historians the traditional account of how it worked is as follows:

The empire was divided into two uneven halves, each of which would have an Augustus as ruler, with the older Augustus being superior, and each having a subordinate called a Caesar. The two rulers would support each other, ruling only over their half of the empire but being permitted to move freely in the other half. The Caesars would effectively be their heirs and adopted sons, carrying out their will, supporting their leaders and ruling over a dangerous frontier region. The senior Augustus would decide on who was to be appointed as Caesars and who would be appointed as an Augustus.

In time these rulers would ideally retire, and their Caesars would take their place with the approval of the senior Augustus.

This system worked at first, but when Diocletian retired as Augustus and forced his co-Augustus, Maximilian, to retire alongside him, disputes soon arose among his successors.

A young man called Constantine saw his father, Constantius, raised to the rank of Caesar by Diocletian and sent to fight a rebellion in modern-day France. This placed Constantine in the line of succession as the next Caesar of the western half of the empire. As such, Constantine went to live in Diocletian’s palace to be educated and groomed for leadership.

When Diocletian retired, Constantine left to join his father in the west at his military base on the island of Britain. His father now assumed the rank of Junior Augustus. But soon after Constantine arrived, his father died, and, on 26 July 306, Constantine arranged for his troops to hail him as Augustus, without waiting for the approval of the senior Augustus. Constantine feigned surprise at his troops demanding he assume the role of Augustus and wrote to the senior Augustus that he had no part in their insubordination but had no choice but to comply with his army’s wishes.

The senior Augustus was furious, but agreed to appoint him Caesar of the west rather than Augustus. The senior Augustus appointed another man as the real Augustus of the west. This state of affairs would not last long and soon conflicts broke out between Constantine and his rival Augustus.

Fatefully, on the eve of battle against his rival for leadership of the western region, legend claims that Constantine had a vision from God that if he painted a Christian symbol on his troops’ shields, he would be victorious. Whatever the truth of the story, Constantine was victorious, and would go on to pass the edict of Milan, legalising Christianity in the Roman empire (which you can read about in a previous This Week in History: https://dailyfriend.co.za/2020/06/19/7517/).

Constantine would ultimately rule all of the Roman Empire as sole emperor, abolishing Diocletian’s ‘tetrarchy’ and becoming one of the most influential leaders of world history, earning himself the historical title, Constantine the Great.

26th July 1509 – The Emperor Krishnadevaraya ascends to the throne, marking the beginning of the regeneration of the Vijayanagara Empire

When Krishnadevaraya arose as newly crowned Emperor of the Vijayanagara Empire, he had assumed control of one of India’s most powerful states and, over the next 20 years, would take the empire to its greatest heights, his rule being remembered as a golden age for Southern India.

For centuries India had faced invasions from the west by various powers. After the rise of Islam, the invaders were mostly Muslims from among the Turkic horse nomads of Central Asia or Persianised Muslim warlords. The various waves of invasion had established a ruling class of Muslim kings, administrators and warriors as overlords of much of India and its mostly Hindu subjects. At various times these overlords were united by one primary power, and at other times were divided into multiple smaller kingdoms. The most recent great power to unite much of India was the Delhi Sultanate which, at its greatest extent, controlled most of India save the Jungles of Orissa and the far southern tip.

Southern India was unique in that most of its rulers tended to be Hindus, but even most of this region had fallen to the advancing forces of the Delhi Sultanate by the beginning of the 14th century. However, this was short-lived and, by 1350, the empire was seriously fragmented. In 1336, as part of resistance to Muslim raids and invasions by the Delhi Sultanate and their successor states, two brothers, Harihara and Bukka, who were Hindu nobles from Southern India, founded a new kingdom which would come to be known as the Vijayanagara Empire.

Over the next few decades this empire expanded, successfully fighting off many Islamic invasions from the north and uniting the many ethnic groups of Southern India. The new empire used its Hindu character as a way of uniting its divided populace against its mostly Islamic rivals. In the early 16th century, however, the empire fell into crisis and was on the verge of collapse.

Then, on 26 July 1509, a new king was crowned; his name was Krishnadevaraya and he would take the empire to its height, reversing the decline and securing its influence over Southern India. Krishnadevaraya was a skilled military leader who was consistently victorious in battle. He also abolished taxes, cracked down on corruption and organised new land to be brought under cultivation by clearing jungle. His reign also brought a flourishing of literature and arts. Portuguese traders newly arrived in India spoke highly of the efficiency of administration and prosperity of the people during his reign. One of his court poets described him thus: ‘O Krishnaraya, you Man-Lion. You destroyed the Turks from far away with just your great name’s power. Oh Lord of the elephant king, just from seeing you the multitude of elephants ran away in horror.’ He would die in 1529, having led Southern India through 20 very successful years.

The Vijayanagara Empire developed a great literary culture and works were written which covered such subjects as religion, biography, fiction, music, grammar, poetry, medicine and mathematics. It also constructed magnificent temples, which still stand to this day, featuring intricate, awe-inspiring sculptures and pillars.

Eventually the empire would be destroyed in 1646; having been divided by civil war, it was finally defeated by its old rival Muslim states to the north.

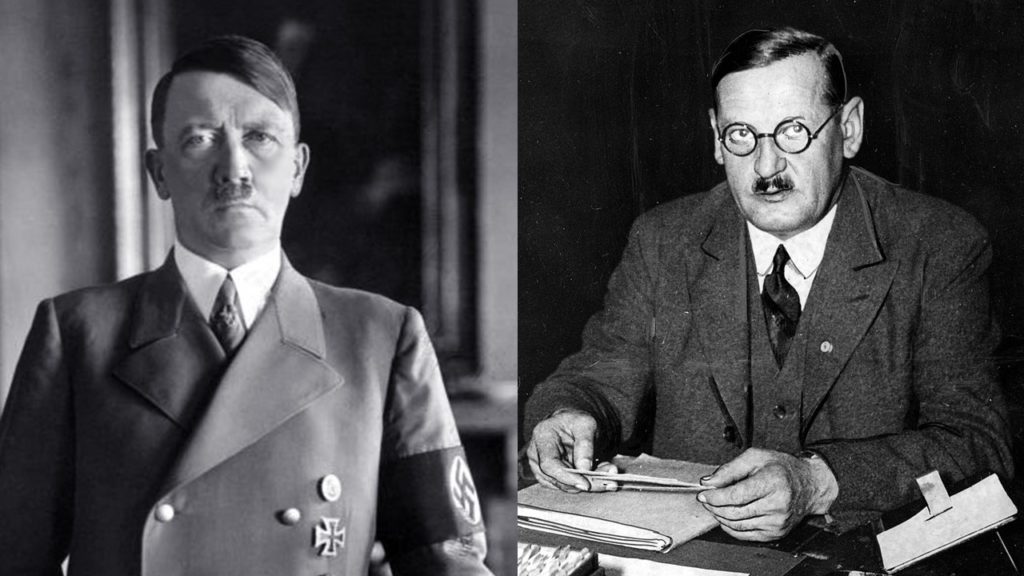

29th July 1921 – Adolf Hitler becomes leader of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party

On 5 January 1919, German nationalist Anton Drexler formed a new political party, which he at first referred to as the German Socialist Workers’ Party. (For a time, it was renamed the German Workers’ Party when one of the cofounders objected to the word ‘socialist’.) This new party was staunchly racist, pro-German, anti-Semitic and sought to find a third way between capitalism and communism, by maintaining the middle class while supporting workers of ‘Aryan’ heritage. The new party advocated the belief that, through profit-sharing instead of nationalisation of industry, Germany should become a unified ‘people’s community’ rather than a society divided along class and party lines.

The party, which was committed to uniting Germany based on race, was also explicitly opposed to international socialist organisations, which it saw as trying to divide Germany on class lines. Though the German Socialist Workers’ Party was a small group with fewer than 60 members, it came to the attention of the German army as a potential threat. To this end, in July 1919, the army sent a low-ranking intelligence officer named Adolf Hitler to infiltrate the group and report back on whether it posed a danger.

Hitler came to the attention of the party leadership when he got into a fierce argument with a visiting professor the group had organized to speak to them in September 1919. He so impressed the leadership of the party that they insisted he join them as a member. With approval from his superiors in the army, Hitler agreed and became a member of the group.

He soon became the party’s star orator, giving fiery speeches to growing crowds.

In 1920, the party changed its name to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, or Nazi Party). In July the next year, the party attempted to merge with the German Socialist Party, but many of its members, including Hitler, protested. Hitler even tendered his resignation, but agreed to re-join on condition he would be made leader to replace Drexler.

At a special party congress on 29 July 1921, Hitler became chairman of the Nazi Party by a vote of 533 to 1.

30th July 1419 – First Defenestration of Prague: A crowd of radical Hussites kill seven members of the Prague city council

In 1415, a charismatic preacher named Jan Hus, who had been critical of the Catholic Church, was burned at the stake for heresy after being promised safe passage by the church authorities. This outraged his followers in his homeland, the Kingdom of Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic). His followers began protesting against the Catholic Church authorities and became known as Hussites. Subsequently, tensions rose in Bohemia between supporters of the Hussite movement and Catholic loyalists.

In 1419, the town of Prague was split between Hussites and Catholics. On 30 July that year, the Hussites decided to march to the new town hall in Prague to demand that the pro-Catholic city council exchange prisoners with them. As the group approached the town hall, their leader, a priest, was struck on the head by a stone thrown from the top window of the building.

The outraged Hussite mob stormed the town hall, grabbed the town council members and threw them out of the windows on to the waiting spears of the Hussites outside.

On hearing the news, King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia was so stunned and died shortly after, supposedly due to shock.

The defenestration was a turning point in relations between Hussites and Catholics and, soon after, as news of the defenestration and the king’s death spread, violence broke out and so began the Hussite wars that would last for the next 15 years.

This defenestration would not be the last. In 1483, there would be another relating to another religious conflict, and a third, in 1618, which began the 30 years’ war.

Defenestrations became symbolic in Czech politics, with multiple killings carried out by throwing people out of windows. In 1948, a prominent Czech diplomat and politician was allegedly murdered by the communists who, it is claimed, threw him from his bathroom window. This is sometimes called the 4th defenestration of Prague.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend