This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

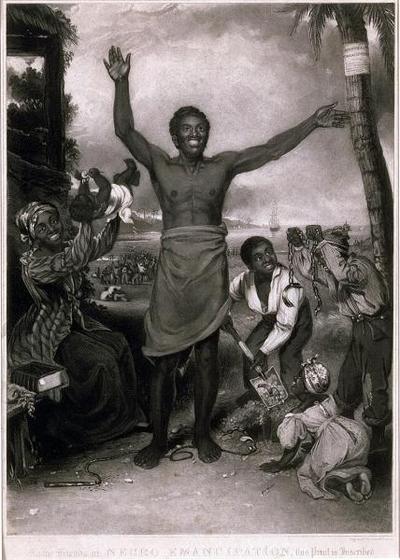

1st August 1834 – Slavery is abolished in the British Empire as the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 comes into force

When the British Empire abolished slavery in all its territories (except India) in 1834, it was not the first attempt at abolishing slavery, it was not the last country to abolish slavery, it likely did not free the most slaves at any one time and it did not instantly free the slaves, and yet it changed the world forever. It would be the beginning of the end of legal slavery across the world, a fight that still continues in some places today but one that has by and large been won.

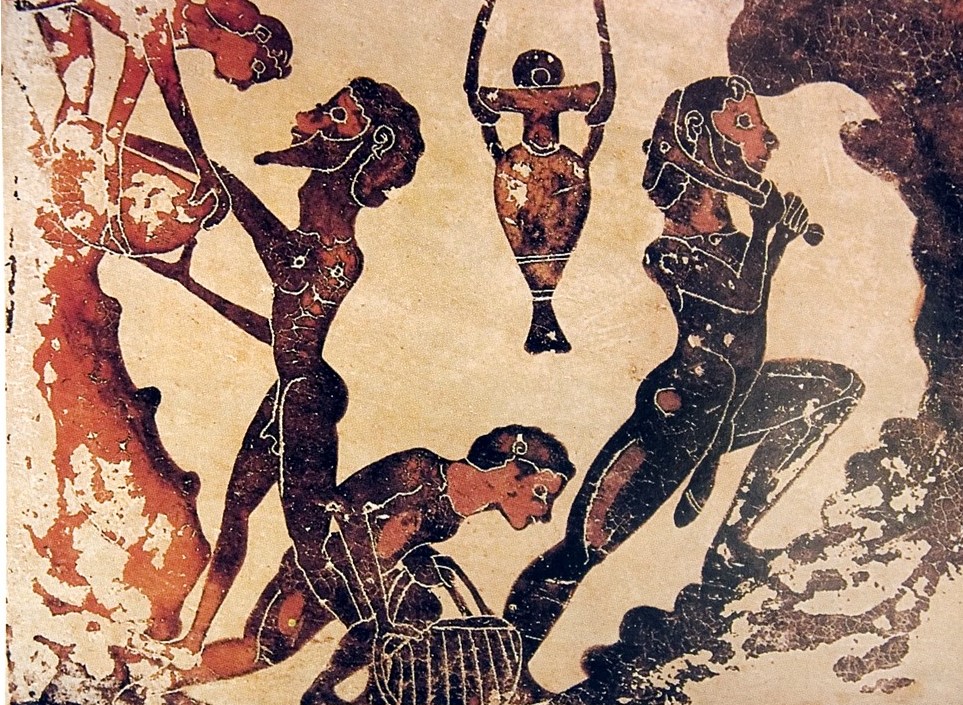

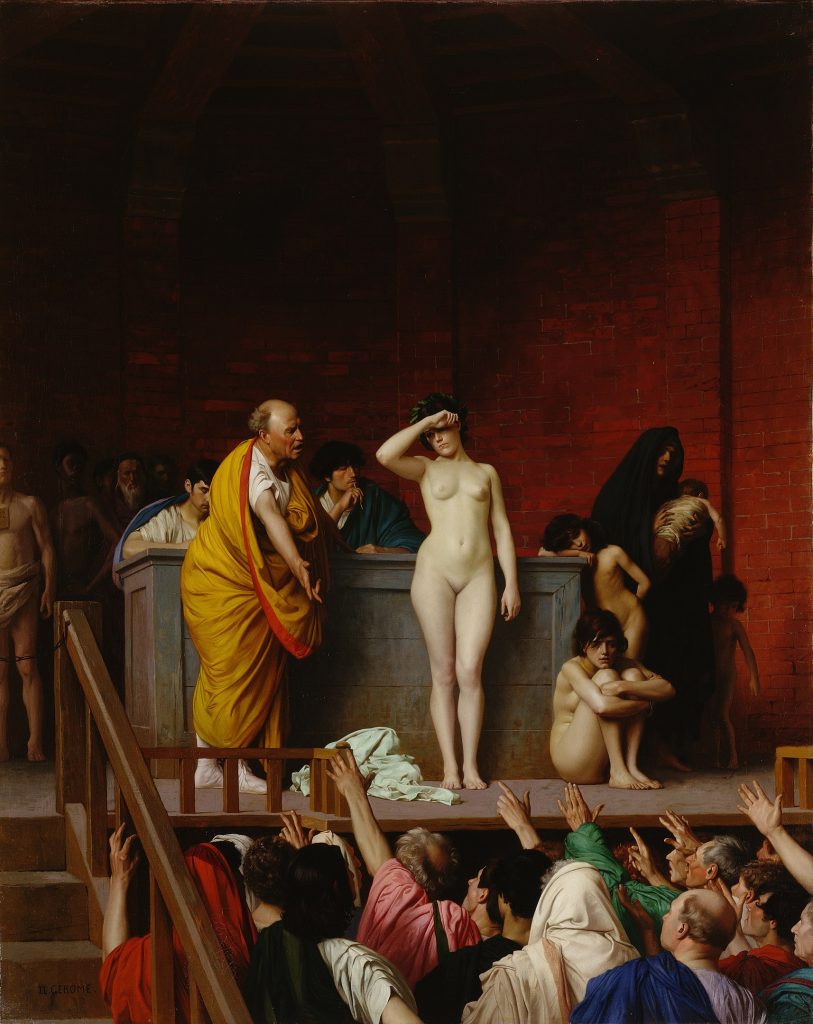

Slavery is one of the oldest institutions in human history. The ownership of human beings has been a feature of every agricultural society on earth going back to the first agricultural civilizations. The first recorded legal code ‘The code of Hammurabi’ from around 1760 BC. details punishment for those who helped slaves escape.

Anyone who has studied Roman law will be familiar with numerous regulations regarding holding and freeing slaves. China, India, Arabia, Africa, northern Europe, and central America all had slaves and the trade in slaves as prominent features of their societies.

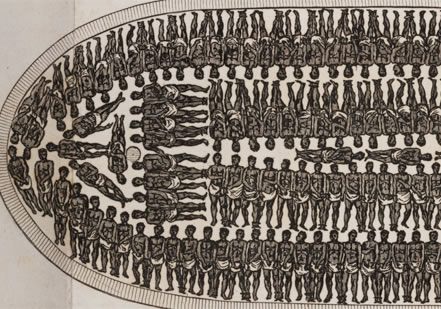

In the late 1400s and early 1500s, the slavery of the popular modern imagination in the west, the Atlantic slave trade, was born. The Atlantic slave trade saw mainly black Africans enslaved in local conflicts by other African states and sold to European traders on the coasts in exchange for guns, alcohol and metal goods. These slaves would be shipped across the Atlantic to the Americas where they would usually be put to work on sugar and cotton plantations.

While there were limited abolitions of slavery from time to time across societies around the world, and whilst in some places, such as England, the practice died out more or less in the medieval period, there were few attempts to seriously dismantle the institution until the late 18th century.

The French revolution of 1789 claimed to abolish slavery, but in the chaos of the revolution and the ongoing wars with European powers little was implemented. The Haitian revolution of the late-18th century, which was a slave revolt against the French plantation owners, claimed to abolish slavery as well, and yet, soon after its independence, the island devolved into an orgy of bloodletting and racial killings, and reimposed slavery under other names.

British abolition of slavery, in contrast to earlier French and Haitian attempts, would definitively shift the balance of forces against slavery and the slave trade worldwide and would lead to the almost total abolition of slavery globally by the mid-20th century.

The roots of British abolition stem from Lord Mansfield’s judgment in the Somersett’s Case in 1772, where he ruled that slaves could not be transported out of England against their will.

The judgment was mistakenly believed by anti-slavery activists to have abolished slavery in Great Britain itself and helped to give encouragement and legitimacy to a movement that had been on the fringes of political life for some time.

In the following decades, the efforts of Christian ministers, activists, changing attitudes to work and workers as well as economic changes turned the anti-slavery movement into a movement with widespread support among the British population.

In 1807, the British banned the international slave trade, but did not ban slavery itself. The Royal Navy would put significant resources into stopping the trade through the creation of the West Africa Squadron, which managed to significantly reduce the sale of new slaves taken from Africa to the Americas.

The British also began to put diplomatic pressure on other nations to abolish the slave trade, efforts that were often successful.

In 1823, the anti-slavery society was founded in London and had many prominent British intellectuals and politicians in its ranks, most notably William Wilberforce. The growing power of the anti-slavery movement was matched by the declining profitability of the slave plantations which reduced slave owners’ political power.

Finally, in 1833, parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which compensated all slave owners for their lost ‘property’ while changing all slaves over the age of six into ‘apprentices’, who would be fully emancipated by 1840.

In 1843, the last territories of the British Empire exempt from abolition would also see slavery abolished, and much of the world would follow suit over the coming decades. The abolition of slavery remains one of the greatest triumphs of human rights and one of the greatest advancements in human liberty in all of history.

Today the only country in which legal slavery remains a serious problem is Mauritania, where slavery was officially abolished in 1981, but largely only to placate foreign aid agencies. There was no sanction for keeping a slave until 2007, when Mauritania under international pressure passed a law to criminalise the keeping of slaves. The law has hardly been enforced, however. Slavery is largely de-facto legal in the country, and in 2017 the country was estimated to still have 600 000 slaves.

Illegal slavery – slavery or forced labour outlawed by government – continues globally and is prevalent in almost every country, particularly in the sex trade and drug trade.

2nd August 216 BC – The Carthaginian army led by Hannibal defeats a numerically superior Roman army at the Battle of Cannae

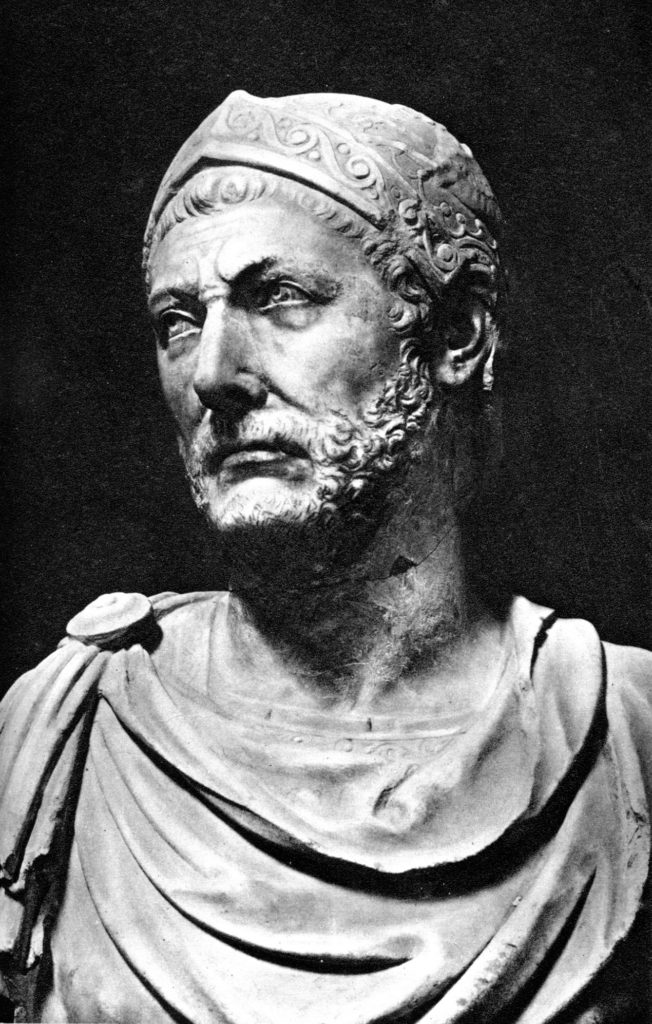

In 216 BC, the Carthaginian general, Hannibal Barca, was rampaging across Italy as part of Carthage’s war against the Roman Republic. This was part of what is called the Second Punic War, the second time Rome and Carthage had gone to war over dominance over the Western Mediterranean. The earlier conflict had left the Romans triumphant, capturing Sicily and Sardinia from the Carthaginians as well as managing to overthrow Carthage’s control of the sea.

One of the leading Carthaginian generals in that conflict had made his son, Hannibal, swear an oath never to be a friend to Rome. Hannibal was now in Italy to make good on the promise to his father.

Lacking control of the sea, Hannibal had marched from his base of operations in Spain across the Alps into northern Italy, where his army of Spaniards, North Africans and various mercenaries from across the Mediterranean had recruited many Celtic tribesmen from the region who had recently suffered defeat at the hands of the Romans.

This army, under Hannibal’s superb leadership and benefiting from his excellent tactical skill, had already defeated the Romans twice in significant battles, at Trebia and again at Lake Trasimene. It had then proceeded to ravage Italy, attempting to turn its cities against their Roman masters. By 216, the campaign had had some limited success.

The Romans, shocked by their defeats, had switched to a strategy of harassment to fight Hannibal, a strategy which had begun to succeed in wearing down Hannibal’s army. However, many in the Roman elite were annoyed by these dishonourable and unmanly tactics and clamoured for a return to open confrontation. Eventually this faction was successful and, in 216, newly elected Roman leaders took the lead of a huge army of 86 000 men to find Hannibal and crush him.

Hannibal by contrast had an army of around 50 000, but his force was well-trained and experienced, unlike the raw recruits of the Roman force bearing down on him.

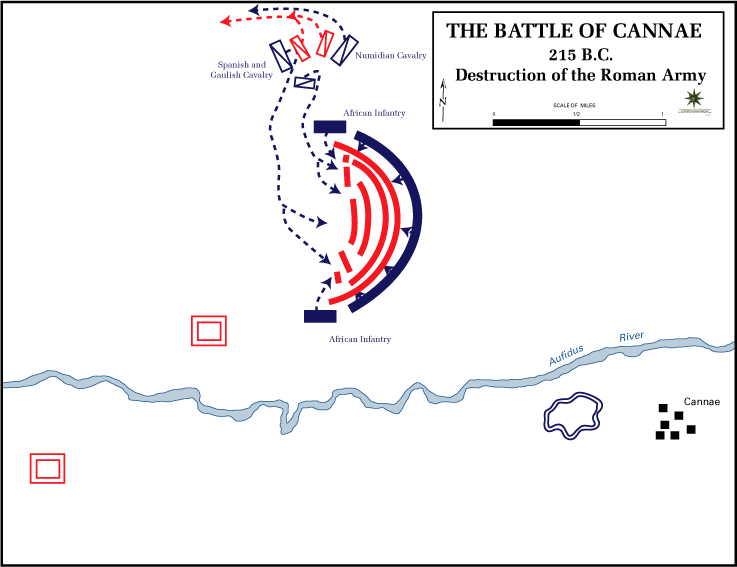

At a town called Cannae in south-eastern Italy, the Romans met Hannibal’s army and prepared to attack, drawing their force of inexperienced troops into a huge square which marched straight at the Carthaginian army.

Expecting this, Hannibal set a trap for the Romans, placing his weakest infantry in the centre of his line, with stronger troops on the wings. He then sent his cavalry out to engage the Roman cavalry.

When the two sides met, the cavalry drew off to the side where they fought each other while the Romans crashed into Hannibal’s line. The Romans pushed back the Carthaginian troops in the centre but were unable to repulse the higher quality troops on the flanks.

This caused the Carthaginian line to bend like a drawn bow so that the flanks now wrapped around the Romans on the left and right. At this point, just as the centre of the Carthaginian line was about to break under the relentless attack of the Romans, the Carthaginian cavalry, having defeated the Roman cavalry, returned to attack the Romans from the rear, completing the encirclement begun by the Carthaginian infantry.

The encircled Romans were so compressed that they could not use their swords.

What followed was one of the greatest slaughters of warfare prior to the modern age. While ancient authors often inflated the numbers mentioned in their records, modern historians tend to believe the Roman historian Livy when he reported that 48 200 Romans were killed and 19 300 were captured, with only around 14 000 escaping the battle. Among the Roman dead and captured were many high-ranking Romans including ‘20 officers of consular and praetorian rank, 30 senators, and 300 others of noble descent’. Hannibal’s army lost around 8 000 troops.

The tactics deployed by Hannibal became so legendary that an American historian in the 20th century wrote: ‘It was a supreme example of generalship, never bettered in history… and it set the lines of military tactics for 2 000 years.’

Despite their horrific loss, the Romans demonstrated incredible stubbornness and decided to continue the war, refusing to negotiate peace terms. Returning to their earlier harassment tactics, the Romans would fight the war for another 15 years until eventually a young general named Scipio took the war to Carthage, forcing Hannibal to return home and defend his North African state from the Roman attack. Scipio defeated Hannibal at the battle of Zama, effectively putting an end to Carthaginian power in the Mediterranean and imposing such a brutal peace treaty on the Carthaginians that we still refer to harsh peace treaties as ‘Carthaginian peace’ agreements.

There is great online content regarding this event. Check out these two videos for depictions of the battle:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MroGPObEZzk

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend