Last week African National Congress (ANC) secretary general Ace Magashule belatedly responded to public outrage over corruption in Covid-19 procurement with a statement acknowledging the ‘depravity’ and ‘heartlessness’ of the ANC cadres who had used the lockdown crisis to pour millions of tax rands into their own pockets.

‘These developments cause us collectively to dip our heads in shame and to humble ourselves before the people,’ wrote Mr Magashule.

The ANC knows it is up against the wall on the Covid-contract feeding frenzy. Since this has cost it much of its (limited) moral credibility, it urgently needs an effective diversion strategy. This it has found in the national executive committee’s proposal for ‘a permanent multi-disciplinary agency to deal with all cases of white-collar crime, organised crime and corruption’.

Not just the Covid-19 contracts, then. Not just corruption either, though this alone looks set to keep the Zondo commission busy for close on three years. ‘White collar’ and ‘organised’ crime will each warrant just as much attention, which is sure to drag investigative processes out for even longer than the Zondo probe requires.

By the time the new agency has finished its initial probes into these three wide-ranging issues, current outrage over the ANC’s ‘depravity’ will have dropped away. In addition, any evidence against the ANC will have been buried in a mountain of allegations against a range of other culprits. Public anger will be diverted to corporate scandals, gang violence, drug abuses, and a list of corruption cases carefully curated to finger the small fry in the ruling party – not Mr Magashule or other senior ANC leaders.

In other words, the ANC plans to use the proven TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission) approach to evade a pressing problem.

Most South Africans have been so misled by ANC propaganda over decades – and so let down by a media far too ready to turn a blind eye to a long history of ANC abuses – that they have little or no knowledge of why the ANC first sought the establishment of the TRC.

In 1993 the ANC had its back against the wall over the executions and cruel tortures it had inflicted on its own Umkhonto we Sizwe members in its camps in exile. Returning exiles had blown the whistle on these abuses in 1991 and four reports had since confirmed them.

In 1992 an inquiry initiated by the ANC and chaired by Lewis Skweyiya found the ANC responsible for murder, torture, and ‘abuses of the most chilling kind’ in its exile camps. Prisoners at the Quatro camp in Angola, in particular, had been ‘denigrated, humiliated and abused, often with staggering brutality’.

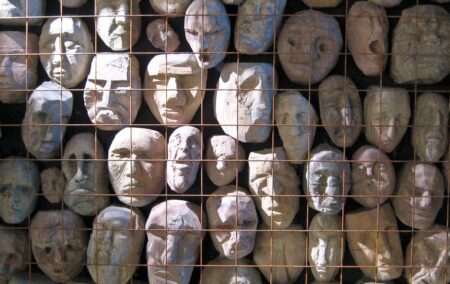

Beaten and tortured

Many detainees had been beaten and tortured to extract confessions. Methods of torture had included kicks to the genitals, along with beatings and burnings to the soles of the feet. Starvation and solitary confinement had also been used. In addition, some prisoners had seemingly been murdered or had ‘simply disappeared’.

‘It was violence for the sake of violence,’ concluded the Skweyiya report. ‘We were left with the impression that, for the better part of the 1980s, there existed a situation of extraordinary abuse of power and lack of accountability.’

The commission recommended that those guilty of atrocities should never again be allowed to occupy positions of power, and that compensation should be paid to victims of torture, irrespective of whether they were spies.

Three subsequent investigations painted a similar picture. The first, by Amnesty International, confirmed the Skweyiya findings. The second, by KwaZulu/Natal advocate Robert Douglas, found the ANC responsible for ‘a litany of unbridled and sustained horror’, marked by ‘tyranny, terror, brutality, forced labour…and mass murder’.

The third inquiry, again commissioned by the ANC, was chaired by Sam Motsuenyane, a prominent South African businessman. The Motsuenyane report was published in August 1993 and confirmed the findings of the Douglas, Skweyiya, and Amnesty investigations. It too urged that those responsible for torture, executions and other abuses should be disciplined and their victims given compensation.

‘Profound regret’

The ANC responded to the Motsuenyane report by expressing ‘profound regret’ for these ‘transgressions’ and taking ‘collective responsibility’ for what had happened. It also said that the ANC could not be singled out for censure, and called for ‘the establishment of a commission of truth to deal with the past’ and investigate human rights violations committed on all sides.

By the time the TRC began its work in 1996, this rationale for the establishment of the TRC had largely been forgotten. The ANC was also able to use its control over the state to dominate the work of the commission. Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a former patron of the United Democratic Front (UDF), the ANC’s internal wing in the 1980s, was appointed chairman. Many of the other commissioners were also overt or closet ANC supporters.

In 1998 the TRC went on to publish a fundamentally skewed assessment of the gross violations committed on all sides in the conflicts of the past. Most of its findings of accountability were based on untested, unsubstantiated and often hearsay testimony. Its report was largely confined to a ‘pre-selected’ list of events calculated to implicate organisations other than the ANC. Many of its findings contradicted carefully considered judicial rulings, which the commission simply distorted or ignored.

One of the TRC’s most telling findings was that the people’s war waged by the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC), a long-standing rival to the ANC, had primarily targeted civilians for attack. This targeting of civilians, the commission went on, was not only a gross violation of human rights but also a violation of international humanitarian law.

Black civilians

However, the TRC made no equivalent findings about the ANC’s people’s war – even though this had been waged for far longer (from 1984 to 1994) and had triggered the deaths of some 20 500 people, almost all of whom were black civilians.

The main target of the ANC’s people’s war was the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), which had wide support in the two most populous regions (KwaZulu/Natal and the Reef) and so had to be eliminated as a political rival before the first all-race election was held. Many thousands of IFP supporters were thus killed. So too were some 400 IFP leaders and office-bearers, many of whom were shot dead in carefully planned attacks. Moreover, when these attacks unleashed major IFP retaliation – which the people’s war strategy was intended to provoke – the IFP assaults were used to strengthen ANC propaganda and blame the IFP for all the terror and the trauma.

The TRC’s report ignored almost all the evidence of ANC wrongdoing. Having failed to examine the ANC’s people’s war, it simplistically concluded that ‘the predominant portion’ of the killings and other gross violations had been committed by the IFP and the National Party (NP) government, acting in collusion with one another.

The commission preserved some appearance of impartiality by holding the ANC accountable for the torture and, on occasion, the execution of suspected ‘enemy agents and mutineers’ in its camps. However, it also took pains to stress that events of this kind were against ANC policy. Similarly, where killings and assaults on ANC political opponents had taken place, this too was against ANC policy – and was largely the fault of the climate of violence and political intolerance created by the NP and the IFP.

The TRC diversion worked. By the time the commission issued its key findings in 1998, more than five years had passed since the publication of the Motsuenyane and other reports and public outrage had petered out. The TRC report was also careful to point the bulk of the blame at the IFP, which was further stigmatised by the commission and its supposedly objective findings.

The TRC was instrumental in letting the ANC off the hook. Much the same tactic – a prolonged investigation with a focus extending well beyond the party’s own culpability – has also allowed the ruling party to escape responsibility for the deaths of the 34 striking miners gunned down by the police in the Marikana massacre in August 2012, now eight years ago.

Serial evasion of accountability

In the corruption context, unlike the people’s war, the public at least has some knowledge of the ANC’s wrongdoing and its serial evasion of accountability. From the 1999 arms deal onwards, the ruling party has repeatedly used the diversion formula to ward off culpability for its massive looting of the public purse.

The formula is a simple one. When outrage at ANC wrongdoing mounts, set up an investigation, widen the scope of the inquiry far beyond the immediate issue, complicate and prolong the investigative process, and undermine the independence and capacity of any entity that might otherwise uncover uncomfortable truths or mount successful prosecutions.

When a corruption-busting agency proves too effective (the Scorpions), close it down and replace it with a compromised alternative (the Hawks). And when public outrage soars to unprecedented heights, as it has over the Covid-19 contracts, pledge to conjure into being a new ‘multi-disciplinary’ investigating agency that will supposedly be just as proficient as the one earlier destroyed.

Make sure this new unit takes time to set up and equip, give it a very wide mandate, and wait for the outrage to dribble away as months turn into years and no clear outcome is in sight. As the final step in the formula, ‘rinse and repeat’ whenever required.

Jeffery is the author of The Truth about the Truth Commission (1999) and People’s War: New Light on the Struggle for South Africa (2009, and 2019 in abridged and updated form)

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend