One of the great things about a sport like cricket is that it lends itself well to statistics. A great player will have great numbers. Of course, there will be something intangible about the Titans of the game, but deciding on who deserves to be one is less subjective than in other sports, such as rugby or football, which don’t lend themselves that well to statistical analysis.

A batsman who averages 30 runs an innings after 40 Test matches is probably not cut out for the top level, ditto a specialist bowler who averages 40 runs a wicket after a similar number of games.

We can do a similar thing with a country’s economic and developmental policies. If there isn’t a resultant uptick in economic growth or per capita incomes, or a decline in indicators like infant mortality, then perhaps those policies are not working.

South Africa is a good example of this. On indicators such as economic growth or income per capita, the country has been trending downwards since 2013. It is clear that the policies of the African National Congress (ANC), which have become increasingly statist since Jacob Zuma became President in 2009, are simply not working.

At the same time, South Africa is declining in comparison to many of its peers around the world. Other countries are getting richer and developing faster than we are. And while the average South African used to be richer than the average world citizen, this is no longer the case.

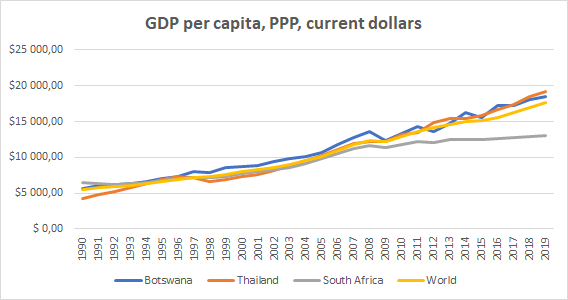

The above graph – using purchasing power parity (PPP) – shows how the average South African was richer than the average Thai, Motswana, or Earthling 30 years ago. They have all caught up with South Africa and South Africans are now poorer than they are, and significantly so.

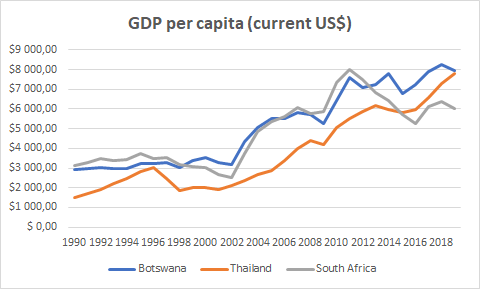

The number isn’t an isolated one. If we look at the similar graph, below, this time without using PPP, the phenomenon is the same, with South Africa’s decline being even more pronounced.

I could be accused of cherry-picking numbers and countries that reflect badly on South Africa in terms of income growth. The fact is, no matter how you measure GDP per capita, at constant 2010 dollars, at PPP or not, the numbers will show the same thing. South Africans are getting poorer and we are falling behind our peers, those in countries at similar levels of development, and globally.

These declines in per capita GDP (using PPP dollars or not) have other consequences. When a country gets poorer, as is the case with South Africa, there is less money to pay for other vital services, such as schools or hospitals. In our case, more and more money is being eaten up by payments to service debt.

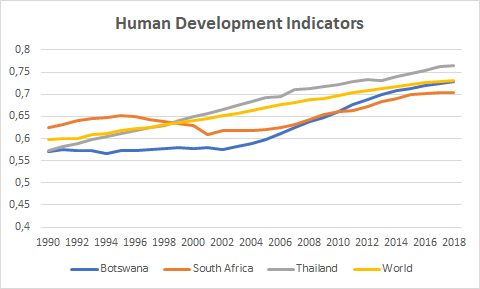

The next graph shows how we have declined on the Human Development Index.

Here, again, it is clear that South Africa, having begun significantly ahead, has fallen behind other countries, and that the average global citizen enjoys a higher standard of development than the average South African.

Now, it is clear that the average South African is richer and enjoys a higher standard of living than in 1990. But it is also clear that the rest of the world has caught up to South Africa and now overtaken us – and that gap is growing.

But to return to my (probably somewhat tortured) cricket analogy, when a cricketer’s statistics shows he isn’t performing, you don’t keep picking him and hope that things will come right on their own. You either do what you can to improve the player’s game or you pick someone else. Doing things the same way and hoping for the best won’t work.

But that is exactly what South African policymakers have done, especially in the last decade or so, and there is no indication that the failed policies of the past decade are likely to be jettisoned. These policies, with an increased role for the state and harsher enforcement of laws designed to ensure demographic representivity, are set to continue to be followed in the months ahead. At the same time, the government has made clear its intention to implement other proposed policies which are guaranteed to set South Africa on the road to ruin, such as expropriation without compensation and the National Health Insurance.

Current policies have failed dismally

But, just as any cricket selector would be remiss in not using available statistics to try something different, there is ample evidence for the government that current policies have failed dismally. Apart from the graphs shown above, on other metrics, such as poverty rates, levels of employment, and economic growth, South Africa is doing poorly. It’s time to do what needs to be done to get South Africa working. It’s time to cut red tape for businesses, reform labour regulations so as to encourage employment rather than discourage it, implement real empowerment which helps the truly disadvantaged, and sell state-owned enterprises, to turn the country around.

The evidence is clear for the team – it’s time to up their game. If the players, in the form of the government, won’t do that, they will need to be replaced. And it’s only the selectors, South Africa’s voters, who can do that.

[Picture: Yogendra Singh from Pixabay]

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend