This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

7th December 43 BC – Marcus Tullius Cicero is assassinated in Formia

Statesman, lawyer, consul, writer and master of Latin, Marcus Tullius Cicero was truly one of the greatest Romans to ever live, but, in the end, the deadly and chaotic politics of the late republican era of Rome would claim his life, and his lifelong ambition to save the Roman Republic would ultimately come to nothing.

He was born on 3 January 106 BC in the small Italian town of Arpinum. His father was a well-off member of the ‘equestrian order’, one of the upper classes of Roman society, but not eligible for entry into the Senate. Cicero’s hometown was looked down on by the Roman elite and his lack of ‘Roman-ness’ would be something that Cicero would feel self-conscious about for his entire life.

An excellent student, Cicero studied under some of Rome’s best lawyers and orators. He wrote poetry and mastered both Greek and Latin writing. During his early years, he also fell in love with Greek philosophy and would become a devotee of the Greek philosophical school of Academic Scepticism.

Cicero would also adopt aspects of the new Stoic philosophy under the influence of some of his friends who were Stoics.

Cicero’s first real taste of political life came with his serving the major political figures, Pompeius Strabo and Lucius Sulla, during the ‘Social War’, when Rome battled many of its Italian client cities who demanded Roman citizenship. Cicero was not a fan of military life and preferred intellectual activities to being on campaign, which for the martial Roman elite was unusual.

At 26, Cicero began practising law in Rome. In 80 BC, he earned the disapproval of Sulla by defending Sextus Roscius on the charge of patricide; Cicero’s skill earned Sextus his acquittal, which annoyed Sulla who was a friend of the murder victim. After this, Cicero became a vocal opponent of Sulla, denouncing his policies in speeches and taking legal cases against Sulla’s interests.

In 79 BC, Cicero left Italy to travel to Greece, Asia Minor and Rhodes, either to avoid the wrath of Sulla – who was now dictator of Rome – or, as he claimed, to improve his physical fitness and his intellectual skills. On this trip Cicero spent some time studying under Greek teachers in Athens and Rhodes, two centres of intellectual thought and learning. In 74 BC, after serving in government in Sicily, Cicero gained entry to the Senate, the first in his family to do so. This made him a so-called novus homo, or new man, a kind of senator looked down on by the elite established families of Rome.

During his early political life, Cicero established himself as a master orator and a committed Roman constitutionalist; he strongly believed in the Roman system of government and upheld the laws of the Roman Republic whenever he was able. Being a provincial and a new man earned him much scorn in the capital and Cicero was only able to rise through the ranks on the back of his talent at speaking and law.

Cicero achieved much wider fame in Rome when he was asked by some Sicilians to prosecute the former governor of the province for corruption and looting, despite the governor’s powerful political allies. Cicero took the case and, despite having to face an opponent considered at the time to be Rome’s best lawyer, and having to overcome political meddling and bribery, Cicero’s masterful oration won the case and cemented his place as Rome’s top lawyer.

In 63 BC, at the age of 42, Cicero was rewarded for his hard work when he was elected to the highest post in the Roman Republic, that of consul. The consul was the leader of the Republic’s armies and its highest authority, with the power to veto legislation. Two were elected every year to serve a one-year term.

The most significant event during his time as consul was when Roman noble Lucius Sergius Catilina attempted to overthrow the Republic with the help of foreign armed forces. Cicero uncovered the plot with his network of spies and denounced the plotters to the Senate in a series of masterful speeches.

Controversially, Cicero had some of those involved executed without a full trial, as he argued that, according to Roman law, their treason had nullified their constitutional rights. It was a decision that would earn Cicero many enemies among the Roman elite who were sympathetic to the plotters.

When Cicero’s term as consul ended, he went back to senatorial politics and was even invited to join the so-called First Triumvirate, an alliance between Julius Caesar (a rising politician) Magnus Pompey (a decorated war hero) and Marcus Crassus (the richest man in Rome). Cicero refused to join, suspecting, correctly, that the alliance would undermine the Republic.

Over the next few years, the Triumvirate would dominate Roman politics until Crassus was killed fighting the Parthians and the alliance between Caesar and Pompey broke down. The resulting civil war was one Cicero hoped to avoid by supporting Pompey but without alienating Caesar. After Caesar and Pompey came to blows, Cicero first fled Rome with Pompey but later returned, seeking to defend the Republic from the Senate floor.

Caesar won the civil war and was established as dictator of Rome and then dictator for life, something that Cicero and many republican senators saw as a prelude to Caesar’s proclaiming himself king. Cicero began to work to undermine Caesar’s regime and re-establish the Republic – but was soon shocked to learn of Caesar’s assassination by a group of senators in 44 BC, a plot which had not included him. In the aftermath, Cicero became a leading figure and tried to broker peace by having the Senate not declare Caesar a tyrant (which would invalidate the laws passed by Caesar) and at the same time granting amnesty to Caesar’s assassins.

This attempt to forge a settlement failed and set off another round of civil wars between Caesar’s heir, Octavian, Caesar’s second-in-command Mark Antony and Caesar’s assassins. Cicero tried to play Octavian and Mark Antony off against each other and have the Senate declare Mark Anthony an enemy of the Republic. He hoped this would succeed in making Octavian a defender of the Republic and lead to Mark Antony’s death – but after the defeat of Caesar’s assassins Antony and Octavian were reconciled.

While Octavian argued that Cicero should be spared, Mark Antony was eager for vengeance and so Octavian agreed to having Cicero declared an enemy of the Roman state. Cicero fled Rome to escape the killers.

Cicero was popular, and few were willing to report his location as he made plans to leave Italy for Macedonia. Having embarked on the journey, he was tracked down by Antony’s soldiers who caught up with him on 7 December 43 BC and set about executing him on the spot.

According to the Roman writer Seneca the Elder, Cicero’s last words were: ‘There is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly.’

Antony had Cicero’s hands and head nailed to the door of the Senate house and his wife, Fulvia, was said to have stabbed Cicero’s tongue with a pin in vengeance against his power of speech.

Antony and Octavian would soon battle each other again, with Octavian emerging victorious and being appointed Rome’s first emperor.

Many historians characterise Cicero as an impressionable man who, being slightly foolish and self-important, shifted political positions and moved often with the political winds and in response to flattery. In my view, he was a patriot, a constitutionalist and a pragmatist who attempted to save a dying Republic from the grasp of authoritarian rule using argument and rhetoric rather than murder and warfare.

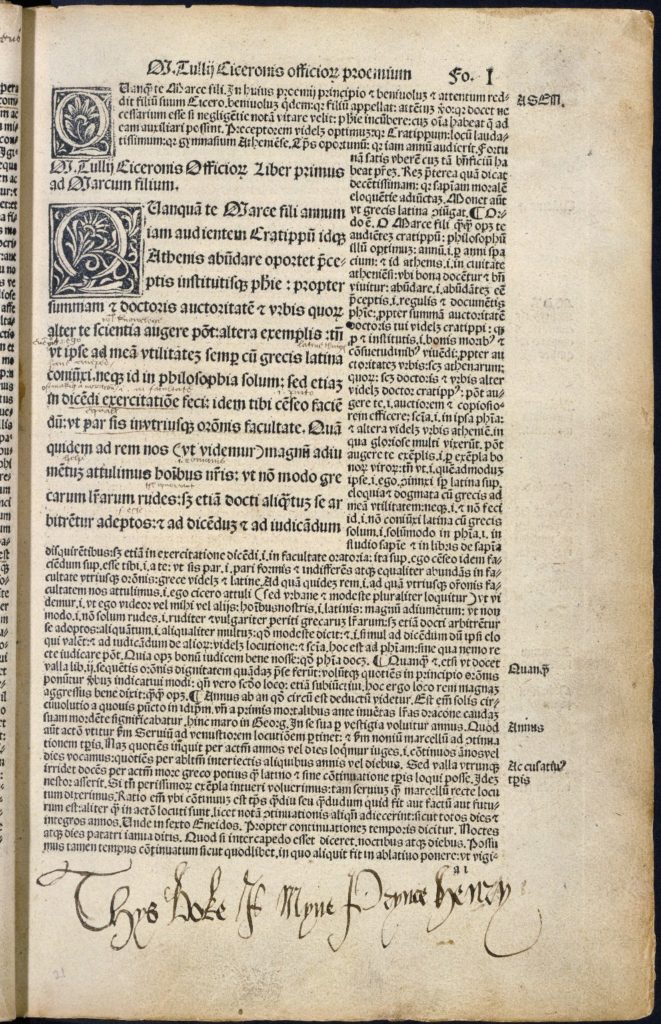

Cicero’s legacy would endure, and his numerous writings and speeches would become the gold standard of Latin writing in the centuries after his death. Medieval and Renaissance writers in particular would copy his style and use him as the basis for their own writing styles.

His letters to friends and his speeches were preserved through the ages and provide historians with unprecedented detail on the final years of the Roman Republic, along with insights – such as the following – which are surely timeless.

“Six mistakes mankind keeps making century after century:

Believing that personal gain is made by crushing others;

Worrying about things that cannot be changed or corrected;

Insisting that a thing is impossible because we cannot accomplish it;

Refusing to set aside trivial preferences;

Neglecting development and refinement of the mind;

Attempting to compel others to believe and live as we do.”

Marcus Tullius Cicero

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend