The year 2020 is behind us, and good riddance to it. It was, on many levels, the worst year since World War II. Yet it taught us some valuable lessons, and even coughed up, reluctantly, a few reasons for optimism.

The year opened with Australia on fire. An unusually severe bushfire season, exacerbated by drought, a hot summer, and poor environmental management went on to kill 33 people, burn over 5 million hectares, and kill an estimated 3 billion animals. A further 445 people are deemed to have died of causes related to the smoke, which makes it the worst natural disaster of 2020, ahead of hurricane Eta, which killed at least 150 people in Central America in November, flash floods which killed a similar number in Afghanistan in August and an earthquake and tsunami which killed 117 people in Greece and Turkey in October.

Environmental activists, of course, tried to attribute the fires to climate change, but that contradicts the long-term trend of a 24% decline in global fires between 1998 and 2015, which trend has continued to 2020.

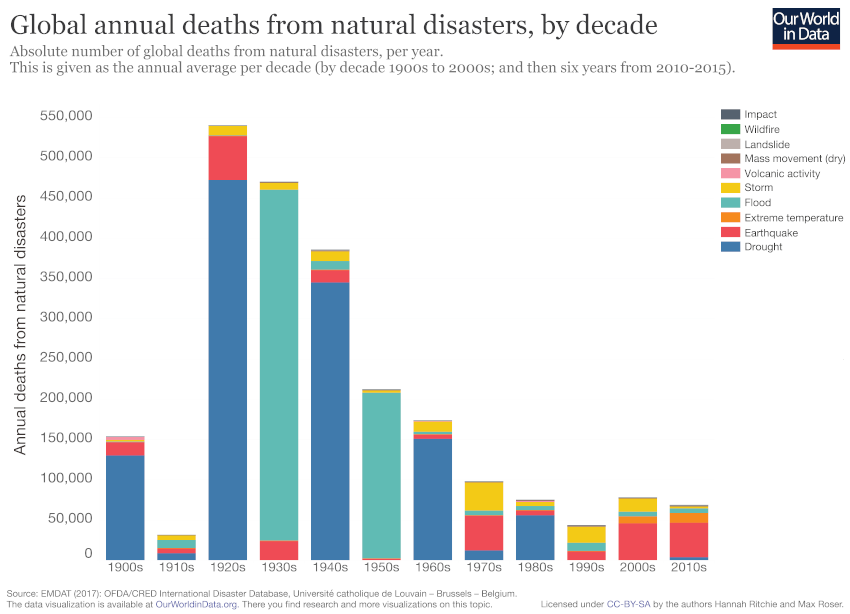

It also contradicts the long-term trend that deaths due to natural disasters have been on a sharp decline for a century. Note that while floods and droughts caused the most deaths in the past, these days earthquakes are the deadliest disasters.

Coronavirus

By the time Australia got its fires under control in March, the world was focused on an entirely new threat, however. The coronavirus pandemic, to which governments responded with an unprecedented wave of harsh authoritarianism, overshadowed the rest of the year.

It killed 1 814 728 people in 2020, among the most recent being an uncle of mine who died on the morning of 31 December.

That number is between three and six times higher than the death toll during a typical flu season, which sees between 290 000 and 650 000 fatalities. While one might dispute the accuracy of the statistics, Covid-19 is certainly worse than a normal flu.

It works out to a crude mortality of 0.02% of the world’s population. Although the pandemic is not yet over, so far it falls short of the crude mortality of the Hong Kong flu pandemic of 1968/9 of between 0.03% and 0.11% of the population, as well as the crude mortality of the Asian flu pandemic of 1957/8 of between 0.03% and 0.14%.

Covid-19’s crude mortality is much lower than that of the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, which was somewhere between 0.94% and 5.56%, having killed at least 17 million and perhaps as many as 100 million of a global population at the time of 1.8 billion.

So this pandemic is serious, but it could have been a lot worse.

What couldn’t possibly have been worse, however, is the global response to the pandemic. In January, the Chinese Communist Party imposed a draconian lockdown on the city of Wuhan and later the entire province of Hubei, which by population is about the same size as South Africa.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) said that the lockdown went well beyond its guidelines, but commended the move nonetheless. ‘The lockdown of 11 million people is unprecedented in public health history,’ Gauden Galea, the WHO’s representative in Beijing, told Reuters, ‘so it is certainly not a recommendation the WHO has made.’

Yet the organisation enthusiastically supported similar lockdown measures around the world. By March and April, almost every country in the world, including South Africa, was under totalitarian rule à la China. Entire economies were shut down. Millions upon millions were turfed out of jobs. Businesses were closed, many of them never to reopen.

In rich countries, there was some measure of individual and corporate relief paid by governments that issued record stimulus packages, printing more money than they ever had before. People in poor countries got little or no compensation.

Ditching all pretence that fiat currencies represent sound money made the cryptocurrency Bitcoin the safe haven of the year. Against the US dollar, its value rose from a low below $4 000 in March, rocketed past its 2017 all-time-high of around $20 000 in early December, and ended the year (at the time of writing) toying with the $29 000 line.

Worst year

We now know that there is little evidence that lockdowns actually achieved their intended effect, which was to ‘flatten the curve’ in order to avoid overwhelming scarce healthcare resources.

Yet the catastrophic economic disaster of lockdowns remains very real. They drove the global economy to its worst contraction since World War II. This has many consequences.

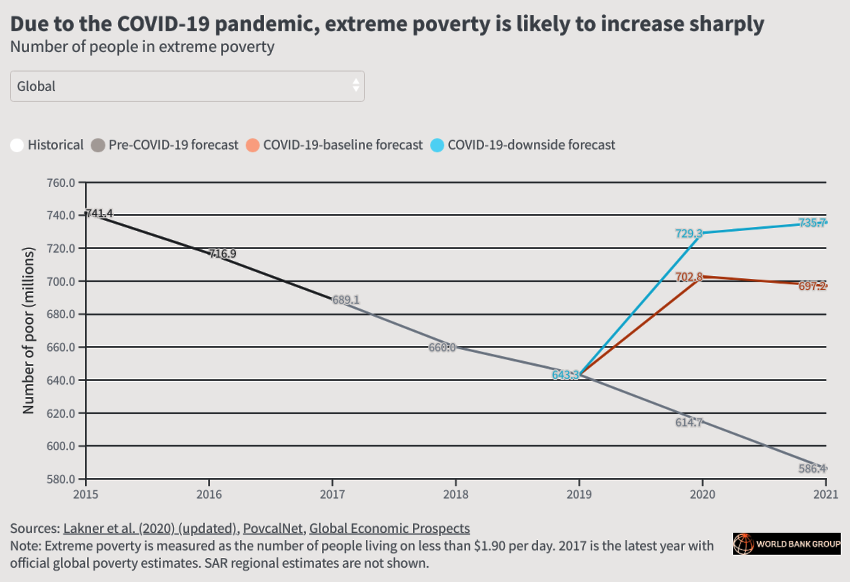

The fight against global poverty, which had been going so well, suffered its first major reversal in decades, sacrificing at least five years’ worth of gains. Some 88 million people are expected to be dumped back into extreme poverty, most of those in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Developing countries, including South Africa, have been left more indebted than ever, which will significantly dampen their chances of economic recovery in the short to medium term.

World Bank surveys suggest that company sales have fallen by half, forcing firms to reduce staff, reduce hours, or reduce wages. Again, the heaviest burden falls on small, medium-, and micro-enterprises in developing countries.

Reduced incomes means families will be forced to make trade-offs and reduce their spending on exactly those things that are essential to a prosperous future, such as healthcare, insurance, education and nutrition.

This is on top of the estimated 1.5 billion children in 160 countries that were sent home from school during lockdowns. Some of them will never return to education.

The World Bank estimates that due to learning losses and increases in dropout rates, this generation of students stands to lose an estimated $10 trillion in earnings, or almost 10% of global GDP.

Food insecurity, which had already been rising in sub-Saharan Africa, will now certainly increase sharply. A preliminary assessment by the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation suggests that the Covid-19 pandemic may add between 83 million and 132 million people to the total number of undernourished in the world in 2020, depending on the economic growth scenario. Their only error is to blame the pandemic, instead of the lockdowns.

But not to worry. The World Bank has a plan. ‘To support a resilient recovery,’ it says, ‘the World Bank Group will continue to make major investments that help countries integrate climate action into their development agendas’.

Whew. At least someone still cares about the weather. Aren’t we led?

We aren’t led

There are many lessons we can learn from all of this.

Governments, despite being well aware that viruses, and coronaviruses in particular, posed a significant threat to public health, were almost universally unprepared for the inevitable pandemic.

Even in nominally free and democratic countries, the response when governments feared that public healthcare systems would be overwhelmed as a consequence of their own lack of preparedness was draconian and totalitarian. Without much thought for the economic consequences, they summarily curtailed rights and liberties that we once took for granted.

To quash resistance, many countries, including South Africa, brought out the military against their own citizens. Soldiers trained only to kill the enemy in war were suddenly expected to police lockdown restrictions.

This had predictably deadly consequences. The most egregious case was the murder of Collins Khosa, who had committed no violation of any lockdown regulations, having been seated in his own yard with half a glass of beer. He was viciously beaten to death by army and police officers. The SANDF found that the soldiers had done no wrong. The court disagreed, and implicated senior leadership all the way up to the minister of defence, who it said encouraged the lawless violence of the soldiers. Nobody has yet been brought to justice.

And who can forget the sight of police minister Bheki Cele, flanked by four generals and dozens of officers, bringing down the full might of the law on unsuspecting bikini-clad sunbathers in Cape Town, like a jumped-up creepy little martinet?

So we learnt that despite having a Constitution that supposedly guarantees our rights, these rights are not inviolable. They can be violated at the whim of cabinet ministers. Parliament has been invisible in this whole debacle, and the courts have been largely supine.

Worldwide, it brought out the authoritarian streak of all but a few governments, dispelling any illusion that we live in a free world.

Draconian and absurd

The measures they imposed were a hodgepodge of hastily chosen restrictions, ranging from the reasonable and sensible to the draconian and absurd.

In South Africa, open spaces were closed, depriving people of the safest place they could be: outdoors. This violates all scientific knowledge on the subject of virus transmission, yet government persists with this policy to this day.

Tobacco was banned, even though study after study showed that smoking is marginally protective against Covid-19.

Very early on in the pandemic, churches and casinos were re-opened, and taxis were permitted full occupancy, even though all three posed massive transmission risks.

This showed that government bowed to powerful lobby groups that could swing either significant money for the government (casinos), significant support for the ANC (churches), or significant violence (taxis).

Industries without such powerful lobbies, such as sports clubs, hotels, guest houses and restaurants, suffered far longer and harder than they should have.

Poor performance

When it came to its own responsibilities, governments universally performed poorly. In South Africa, procurement contracts for ventilators, personal protective equipment and the other necessities of a public health response became a feeding trough for the corrupt.

Nine months into the pandemic, government still has not got hospitals ready to deal with even a fraction of the volumes of patients that were widely expected and predicted.

The South African government has also failed to make any arrangements for early access to vaccines, or for enough vaccines to mount a widespread immunisation campaign. Even for the small shipment of vaccines it did arrange, it more than once failed to make payments on time, eventually having to turn to charity to make payment.

That immunisation drives have begun worldwide, while even South Africa’s healthcare workers – who every day risk their lives and the lives of their families to fight Covid-19 – won’t see a vaccine until sometime in the second quarter, is shameful.

Great Reset

The actions of the South African government, and governments around the world, should dispel once and for all the notion that government is competent and acts in the best interests of citizens. Government is a necessary evil, but it must be restrained. We now have proof that governments, even in free and democratic countries, will turn totalitarian and destroy entire economies in a matter of weeks, given the right excuse.

We do need a Great Reset, but not the eco-socialist wet dream of the World Economic Forum (WEF), which would see governments assume even more powers and control even more of the economy.

In the WEF’s vision, we would have ‘free markets’, but only in goods and services approved by government, and taxed according to government’s priorities.

Politicians and wealthy elites – and not the people – would determine ‘the future state of global relations, the direction of national economies, the priorities of societies, the nature of business models and the management of a global commons’.

The Great Reset we really need is the recognition that governments are the problem, not the solution.

As Jeffrey A. Tucker writing for the American Institute for Economic Research so eloquently put it, we need to recognise that governments are not the ‘machinery of compassion, justice, equality, fairness, and high regard for human dignity, the essential bulwark that keeps civilisation afloat’.

Governments themselves tossed all these values out the window when faced with a crisis, and instead moved to command and control citizens and bolster their own authoritarian powers.

We need a political reset that would take the big red economic stop button away from incompetent, corrupt and power-hungry politicians.

We need truly free markets, in which governments protect life, liberty and property, and provide only a minimal set of public services but do so very well, and in which citizen’s rights and freedoms are protected against the capricious actions of their own governments.

Instead of wasting untold fortunes maintaining standing armies against foreign enemies that never come, for example, some of that funding could be redirected towards maintaining a standing public health corps, with the ability to respond when pandemics strike, and when they don’t, to provide mental health support services.

Idiots and sheep

I am not optimistic that we’ll get such a political reset. Besides the failures of government, the year has also laid bare the nature of many of our fellow citizens.

On the one hand, you have the sheep, who truly believe that government is doing the best it can, and that every violation of our rights and freedoms is a necessary measure to protect lives. These are the people that will praise the state for condemning them to the Gulag.

On the other, you have the idiots, who rightly distrust government, but take their distrust so far that they believe the Covid-19 pandemic is fake, that health precautions are not prudent, or that well-tested vaccines are dangerous but untested drugs are the wonder-cure. These are the people that party like it’s 1999, with scant regard not only for their own lives, but also those among the far more vulnerable population they might infect.

Sadly, rationalists who do believe the pandemic is serious, but don’t believe authoritarian governments can save us, are few and far between. Resisting the political polarisation and fake news fuelled by untrustworthy traditional media and instant social media is hard.

Looking forward

Lest I contribute to the mental health crisis of 2020 caused by harsh lockdowns and pandemic fears, let me review a few positives we can take from the year.

Hopefully, the loss of faith in government is one of them, but there are others.

This pandemic could have been a lot worse. I dread to think how governments will respond when (not if) we do get a more deadly one, but I would hope lessons were learnt.

Medicine has advanced to such an extent that we are no longer powerless against disease. If this pandemic had happened 50 or 100 years ago, untold many more would have died.

Perhaps the most encouraging development of the year was the coming of age of mRNA technology, which was used to produce a vaccine in two days flat, back in January. The idea that we can effectively programme drugs to do exactly what we need them to do will have awesome implications for the future of medicine.

Technology also took a front seat in 2020, as video conferencing saw a wave of adoption in business and education, to help keep listing ships afloat. I don’t live in a big city, so I rarely get to attend face-to-face meetings. Thanks to virtual meetings, I’ve never felt more connected to others than I did during lockdown in 2020.

Technology will continue to bring people together and make work more efficient into 2021 and beyond.

Although the global economy took a massive knock in 2020, it will recover. Progress in advancing prosperity and happiness has been relentless in the last few centuries, but not without occasional, and sometimes grave, setbacks. If our grandparents could recover from the Great War, the Spanish flu, the Great Depression, Prohibition, and World War II, we can certainly recover from 2020.

Let’s be realistic. Lost ground is lost ground. Twenty years from now, we’ll still be less prosperous than we would have been had 2020 not happened, and we’ll have lockdowns – not the pandemic – to blame. However, we’ll be more prosperous than we were in 2019. In 50 years, we’ll be more prosperous, healthier and happier still.

With any luck, we’ll also still be free. The price of liberty is eternal vigilance, as the old saw goes. Let’s enter 2021 with hope and freedom in our hearts, and with renewed vigilance on our minds.

Happy New Year.

[Picture: Kjerstin Michaela Noomi Sakura Gihle Martinsen Haraldsen from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend