This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

16th January 1707 – The Scottish Parliament ratifies the Act of Union, paving the way for the creation of Great Britain

Queen Elizabeth I of England died childless in 1603. Two decades earlier, in 1578, with no sign of marriage or children in sight, members of parliament encouraged her to name a successor so that England could avoid the chaos of a disputed succession.

The candidate she eventually settled on was King James VI of Scotland, who was appointed as her heir. Upon her death, James assumed the throne of England and became ruler of both England and Scotland. However, this did not make them into one fully unified political body.

Both England and Scotland had separate political structures, and different relationships between king and parliament. Most importantly, the English parliament saw James as effectively an absolute ruler of Scotland and the parliament there as weak.

When, as James I, he assumed the throne on the death of Elizabeth, he sought to unify the kingdoms of Scotland and England into one political body and an act of parliament to this end was drawn up. This was strongly opposed by the nobles of England, who saw this as a stealthy way to reduce their power and make them as subservient as their Scottish counterparts. This led to the failure of the attempt to unify the kingdoms.

The next 100 years were very eventful for both England and Scotland, with considerable internal conflict and chaos. Monarchs occasionally used the Scottish and English parliaments against each other in order to grow their own power, which ultimately undermined the parliaments’ resistance to the idea of unification.

By the beginning of the 18th century, the political climate was much better suited towards uniting the kingdoms. Across Europe kingdoms were centralising their political structures and beginning to construct what today we would recognize as the modern state.

In addition to this, in the 1690s the Scottish had attempted to colonize a region of central America, an expedition that ended in disaster and bankrupted the relatively poor kingdom. The Scots needed a bailout and the English used economic sanctions to encourage the Scots to negotiate a union.

Eventually, in 1706, the English parliament passed the Act of Union and on 16 January 1707, the Scottish parliament followed suit, passing its own Act of Union by 110 votes to 69.

From that point forward the Kingdoms of England and Scotland were no more, and have remained united as the Kingdom of Great Britain.

17th January 1917 – The United States pays Denmark $25 million for the Virgin Islands

When one thinks of the colonial powers of Europe who conquered much of the world in the 19th century, the small Scandinavian nation of Denmark doesn’t leap to mind.

Unknown to many today, Denmark actually set up a few colonies – and one of these was the group of islands today known as the American Virgin Islands.

The Virgin Islands have been inhabited for over 3 000 years by human beings, though we know little about these peoples. The oldest known groups to inhabit these islands were the Ciboney and Arawak, and around 1 500 Carib people began migrating to the islands.

In 1493, on his second voyage to the Americas, Christopher Columbus is thought to have been the first European to see the islands, which he named the Virgin Islands, after the Virgin Mary. In 1555, the Spanish settled one of the islands, and in 1625 French and English settlers also arrived.

Until the early 18th century the islands would be claimed by Spain, France, Britain and the Dutch.

In the mid-17th century, the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway (a union between the two kingdoms under one king dominated by the Danes) sought to join the colonial rush and get a slice of the Caribbean islands for themselves. To this end, they established a colonial company, the Danish West India Company, to explore and settle the New World.

The Danes settled one of the three major islands in the Virgin isles in 1672, another in 1694 and purchased the third in 1733 from the French. This began the period of Danish rule over the islands, which saw the establishment of a sugar industry.

In 1733, African slaves, originally from Ghana, launched a successful rebellion and occupied one of the islands until the Danes and French defeated them and retook the island. The Virgin Islands would pass from the Danish East India Company to the Danish crown in 1754.

In 1848 another major slave rebellion took place and, once it was crushed, the Danish governor decided to abolish slavery. In the following decades the islands would be hit by significant hurricanes, and labour disputes would cause most of the sugar plantations to go bankrupt, prompting most of the island’s Danish population to leave.

During the 19th century, the growing United States had taken an interest in these islands and a treaty was drawn up to buy them from Denmark in 1867. However, this was abandoned, and the issue went dormant for decades. In 1902 another treaty to sell the islands was defeated by one vote in the Danish Parliament when the opposition carried a 97-year-old MP into the chamber to cast the winning vote.

When the First World War broke out, the United States feared that Germany would pressure Denmark into giving it the islands so that it could use them as a base to launch submarine attacks. Eager to prevent German encroachment into the western hemisphere, the American government offered to buy the islands for $25 million (about half a billion dollars today.

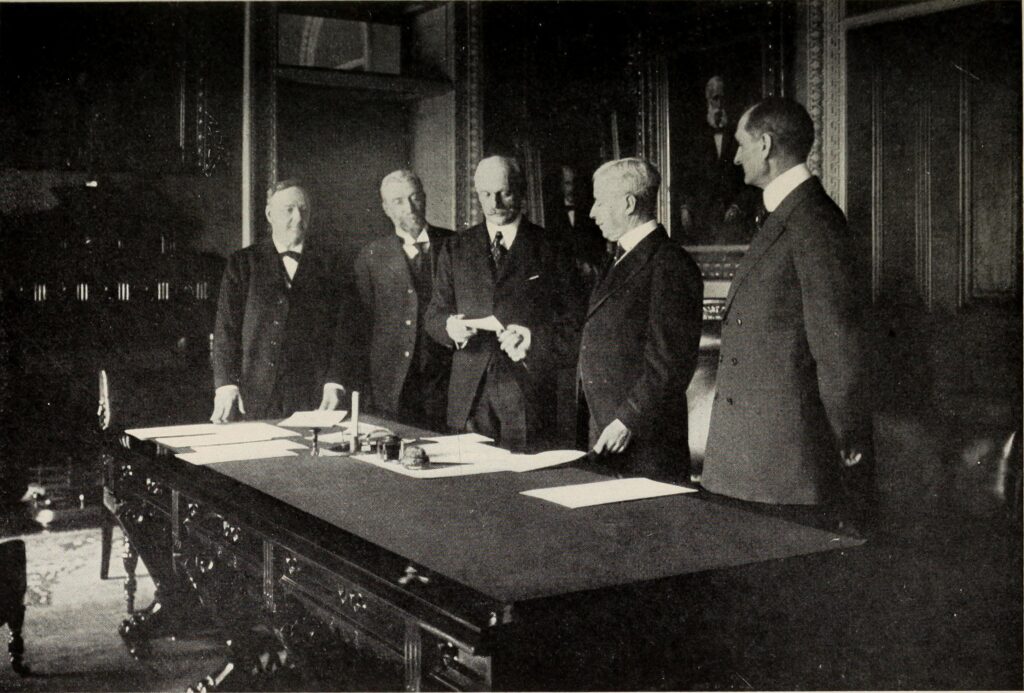

The deal was ratified in both the United States and Denmark in 1916, and the islands came under United States control on 17 January 1917.

21st January 1960 – A coal mine collapses at Holly Country, South Africa, killing 435 miners

On 21 January 1960, around 1 000 miners, most of them from Basutoland and Portuguese East Africa, were at work underground in a coal mine in the northern Free State, 21km from Vereeniging.

The mine was working hard to supply coal to the newly contracted nearby Taaibos coal power station. In particular, the mine was ‘top coaling’, where the ceiling of every tunnel is mined, raising its height to access coal which had been missed by previous mining efforts. The mine had been open since the early 20th century and as such had numerous tunnels which had occasionally been ‘top coaled’ over the preceding 50 years.

The new power station was able to use much lower quality coal than the mine had previously been supplying and the easiest place to get this coal was the roof of old tunnels. So, from 1951 onwards, the mine embarked on extensive ‘top coaling’.

These efforts caused some tunnels to collapse, notably on 29 December 1959, but these were largely ignored.

Less than a month later, on the afternoon of 21 January, miners working underground reported 10 noises from the south-east section and strong blast winds, and rushed for the exit.

It soon became apparent that a major disaster had occurred, and 435 miners were missing. The raising of the roof of the tunnels and the weakening of the pillars holding up the shafts caused by ‘top coaling’ had weakened the mine, which led to a cascading failure where pillar after pillar collapsed, each collapsing pillar weakening the next.

Rescue efforts were quickly attempted but the rescue teams could not get down into the shaft as the collapse had released large amounts of methane and carbon monoxide. The rescuers instead drilled holes down into the shafts to try and determine if anyone was alive.

When microphones were lowered into the shafts, they detected no signs of life. All 435 miners lost their lives in what is still today South Africa’s worst mining accident.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend