This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

29th January 1980 Rubik’s Cube makes its international debut

Most people are familiar with the Rubik’s Cube, a puzzle consisting of a cube of moveable interlocking blocks with different coloured sides which can be scrambled and – by trial and error, or analytical acuity – manipulated to present a single colour on each side.

The toy was originally invented in Hungary in 1974 by Ernő Rubik who worked at the Department of Interior Design at the Academy of Applied Arts and Crafts in Budapest. Rubik patented the toy in Hungary on 30 January 1975.

The cube was originally created to help solve the structural problem of enable component parts to move independently without the whole cube falling apart. He only realized that the cube could be a puzzle when, having scrambled it, he set out to get it back to its original form.

The first versions of the toy were produced in 1977 and sent out to toy shops in Hungary to see how well they sold. The toy was sold under the name ‘Magic Cube’. Soon after, the toy design was sold to a German businessman, Tibor Laczi, who took the cube to the Nuremberg toy fair in 1979. There it was sold to a toy manufacturer and renamed with the more memorable Rubik’s Cube. In late January of 1980 the toy was revealed to the world at the toy fairs of London, Paris, Nuremberg, and New York.

Ever since, it has proven extremely popular and is an iconic toy often associated with intelligence and nerd culture.

If you ever wondered how to solve a Rubik’s Cube, wonder no more; here is a video tutorial on how to do it: How to Solve a Rubik’s Cube | WIRED

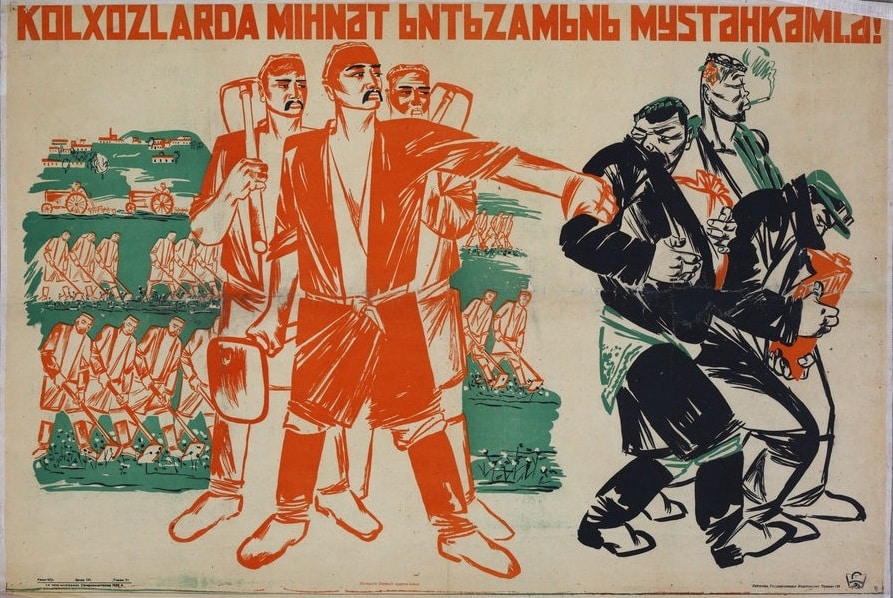

30th January 1930 – The Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union orders that a million prosperous peasant families be driven off their farms

Stalin is rightly remembered by history as one of its worst monsters. A cynical and brutal man, his reign over the world’s largest country has left an enormous mark on the history of the world, and still shapes the lives and politics of millions of people, particularly in central Asia, to this day.

It is worth mentioning that the terror inflicted by Stalin was for the most part not new for the Soviet system. Since taking power in an armed uprising, the Bolsheviks had used brutality, summary execution, plundering, exile to Siberia and torture as weapons to secure their regime. Stalin, however, took these practices to their height during his reign.

While many are aware of his brutality, the specifics are often less well known. Perhaps his most infamous was the programme of Dekulakization, which began on 30 January 1930.

Dekulakization was part of Stalin’s programme of modernization, socialisation and industrialisation, carried out from 1929 to the mid-1930s. These were known as the five-year plans and sought to move Soviet society away from the social and economic structures that had predominated during the Tsarist period and into a modern socialist age.

A persistent source of concern for the Soviet regime were the slightly better-off peasants in the countryside, who ranged from relatively middle class to quite wealthy. These ‘kulaks’, as they were known, were often opposed to the socialist programme of collectivised farming, as this often meant the loss of their property and their impoverishment.

Additionally, the kulaks had more resources and material security, which allowed them more independence from the Soviet government, a potential source of future resistance to Soviet rule.

Furthermore, given the destruction wrought by the First World War, the Russian civil war and Soviet policy, which had devastated the country, leaving millions of peasants either starving or close to starvation, the Kulaks with their stores of wealth and grain provided excellent scapegoats for the Soviet regime. During the civil war the Soviets had often confiscated grain from peasants as a temporary measure, but this was soon turned into a permanent policy, as it became one of the tools by which to ‘destroy Kulaks as a class’.

On 27 December 1929, Stalin in announced to the Soviet Politburo that now was the time to engage in the ‘liquidation of the kulaks as a class’, and that this was critical to the successful collectivisation of farming, and to preventing “counter-revolution”.

Over the next two years, more than 1.8 million peasants were deported from their homes to resettlement in Siberia or imprisonment in work camps. Others were shot or imprisoned, and some were sent to local labour colonies.

Additionally, propaganda campaigns encouraged poorer peasants to help destroy kulaks and this led to violence and theft carried out against anyone labelled a kulak. So flexible was the definition of kulak that even only modestly well-off peasants who were slightly wealthier than their neighbours might be killed or evicted from their homes.

By the end of the programme, anywhere between 500 000 and 5 million people had been killed through starvation, brutal imprisonment or execution. Resistance to collectivisation and the collectivisation itself caused additional food shortages and quality problems which would plague the Soviet Union for its whole existence.

3rd February 1830 – The London Protocol of 1830 establishes the full independence and sovereignty of Greece from the Ottoman Empire as the final result of the Greek War of Independence

What is today modern Greece first began to come under Ottoman rule in the 1300s when the Ottoman Sultans were brought into Europe in 1354 by a claimant to the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) throne. From that point onwards the Ottomans slowly conquered more and more modern Greek territory until by the 1500s they controlled almost all Greek territory.

The nation of Greece as we know it today had not existed prior to Ottoman rule. Greece had been ruled by the Roman Empire since the 200s BC and Greeks had for the most part taken on Roman identity. For hundreds of years, they had seen themselves as the true Romans, and regarded the Italians simply as barbarian pretenders to Roman heritage. After the fall of the Western half of the Roman Empire in 476, the already very Greek eastern half only became more Greek in character over the centuries. Importantly Greeks, far more than today, were also scattered around the Agean Sea, living both in modern Greece and western Anatolia. What existed of the Greek ‘nation’ was more a vague cultural and linguistic identity than anything we would recognise today as a clearly defined nationality.

Under Ottoman rule there were several revolts by Greek peoples, but all of these were of fairly limited impact and were often encouraged by foreign enemies of the Ottomans such as the Venetians or the Russians.

However, in the early 19th century, sparked by the growing revolutionary fervour and ideas of modern nationalism spread by the French during the Napoleonic wars, some Greeks began to organise for a new rebellion against the Ottomans to free what they saw as the Greek ‘nation’. They formed a group called the ‘Friendly Society’ in 1814, and sought support from wealthy Greek exiles and foreign governments for their planned uprising. Greeks abroad provided funding and the Russian government soon began to covertly support the rebellion.

On 21 March 1821, Orthodox Bishop Germanos of Patras proclaimed a national uprising.

The Ottomans immediately retaliated with massacres of Greeks in Constantinople and Smyrna. The Patriarch of the Greek Orthodox Church, Gregory V, was publicly hanged despite having condemned the revolution and preached obedience to the Sultan in his sermons.

This in turn prompted the Greeks to respond violently, carrying out massacres of Turks, Albanians and any Muslims across all Greek-speaking areas. As a reprisal, the Ottomans massacred the Greek population of Chios. Fighting and violence would continue between the Greek nationalists and Ottoman army for the next four years, with the Greeks becoming internally divided and fighting as much among themselves as against the Ottomans.

In 1825 the Ottomans sent a large fleet to bring an end to the rebellion, which – coupled with news of Ottoman atrocities against Greek Christians – encouraged the British, Russians and French to intervene on the side of the Greeks.

At the Battle of Navarino in 1827, a combined Russian, British and French fleet smashed the Ottoman fleet and greatly weakened the Ottomans’ ability to fight the Greek rebels. In 1828 French and Russian troops helped defeat the Ottoman forces and, finally, in 1829 the Greeks defeated the Ottoman army at the Battle of Petra, bringing the war to an end.

At a peace conference in London, it was initially proposed that Greece become an autonomous region under nominal Ottoman rule. As negotiations progressed, this was changed to full independence. The Greek state was formally recognised at the 1832 London Conference.

This was not the end of the story of conflict between the Ottomans and Greeks, however; well into the 20th century and after the foundation of the Republic of Turkey, Greeks and Turks would continue to fight for control of the Balkans and Anatolia.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend