This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

12th February 2019 – The country known as the Republic of Macedonia renames itself the Republic of North Macedonia in accordance with the Prespa agreement, settling a long-standing naming dispute with Greece

Where is Macedonia? It may seem like a simple question, but divergent answers to it have caused trouble since the early 20th century, and underpin one of the strangest international disputes of recent years.

From about the 500s BC, prior to its conquest by the Roman Empire in 1st and 2nd century BC, the region of the south-central Balkans was home to a kingdom known as Macedonia. The Macedonians were not quite Greeks but were also not quite ‘Barbarian’.

They interacted with the Greek world, and for a time were vassals of the mighty Persian Empire. In 359 BC, the Macedonians were catapulted from small kingdom to Mediterranean superpower when a new King Phillip II was crowned.

Phillip set to work expanding Macedonian control over the Greek-speaking world, and when he was assassinated his son, Alexander III – also known as Alexander the Great – led his father’s armies and kingdom in a lightning conquest of the once immense Persian Empire.

For a time Macedon and its successor states were important players in the Mediterranean and Middle East. Eventually the Romans conquered Macedon and converted it to a province called Macedonia, which stretched further north than the original kingdom had.

Centuries later, during the 6th Century, Slavic tribes (the ancestors of modern-day Serbs, and Bulgarians) began migrating en masse into the region as the Romans began to lose control. They heavily settled the Balkans, including much but not all of historical Macedonia. Much of this region would pass from Roman, to Bulgarian, to Serbian and eventually to Ottoman control over the centuries. For around 400 years Macedonia remained forgotten as it was now a piece of the Ottoman Empire, called Rumelia.

However, after the 1830 independence of Greece from the Ottoman empire (covered in this edition of This Week in History), the name Macedonia was revived by Greek nationalists seeking to bring the region of historical Macedonia under Greek control, as it was still held by the Ottomans.

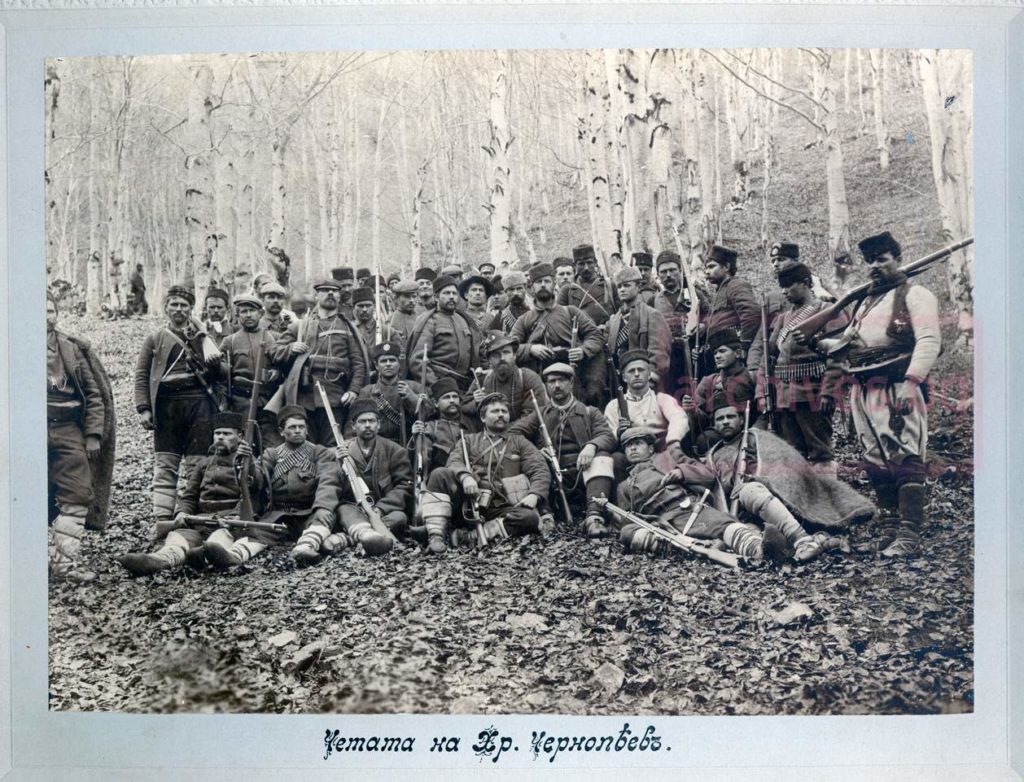

A revolution broke out in this region against the Ottomans in 1903 but was unable to eject the Ottomans. However, Serbs, Bulgarians and Greeks in the area continued to fight against Ottoman rule.

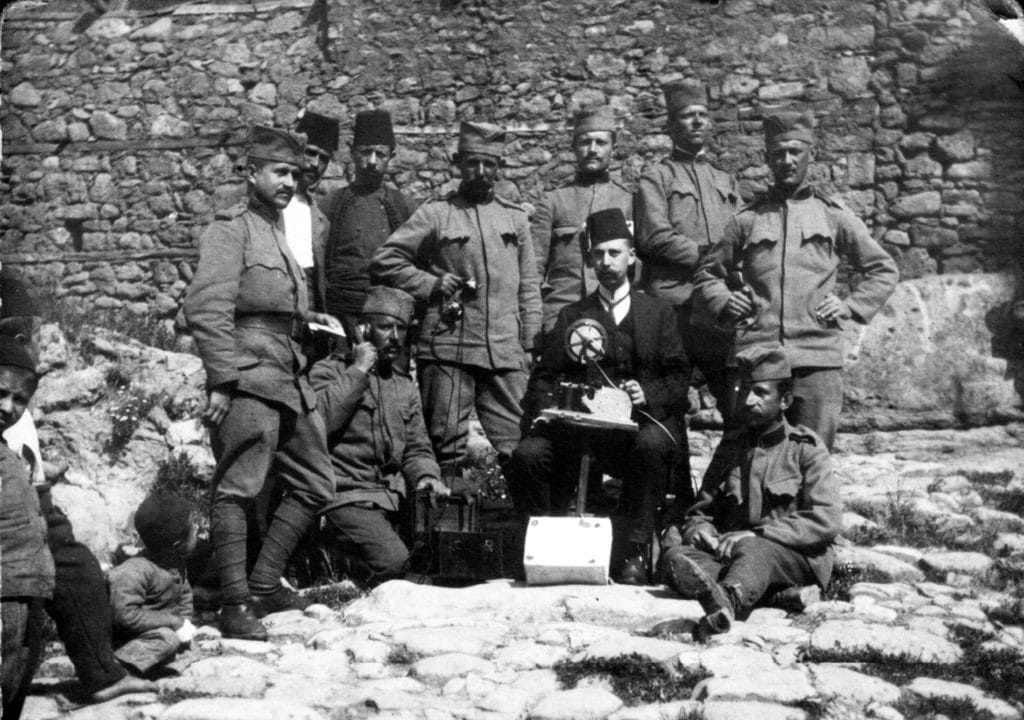

In 1912, the Ottoman Empire in Europe was collapsing and the various Balkan ethnicities were preparing for war against their former masters. In the First Balkan War of 1912-1913, the Balkan nations of Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro united against the Ottomans and in seven months crushed their forces, driving them almost entirely out of Europe.

The treaty of London which ended the war saw the historical region of Macedon split between Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria. The Bulgarians believed that Macedonia should be theirs and so attacked Serbia and Greece, starting the Second Balkan War.

In the end the region remained mostly split between the Kingdoms of Serbia and Greece. In 1914, when the First World War broke out, Serbia and Bulgaria found themselves on opposite sides again. Eventually, however, Bulgaria would lose the war and Serbia would be granted Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Montenegro and some of southern Hungary to form the Kingdom of the South Slavs, known as Yugoslavia.

The part of Macedonia which remained in Serbian hands became the province of Vardar Banovina, while the south remained in Greek hands as Macedonia.

In 1941, during the Second World War, the whole region of Macedonia was occupied by the Nazi regime and their Bulgarian allies.

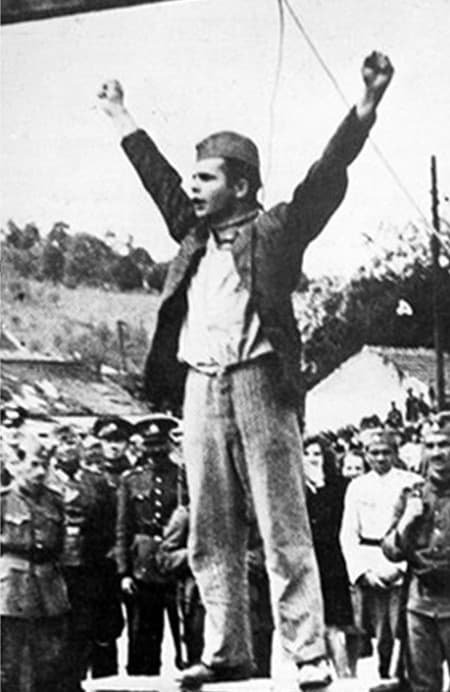

The Yugoslav communist partisans took up the fight against Nazi control, resistance which began in the northern part of this region and soon spread to the rest of the country.

A year after the war, in 1946, the Yugoslav part of Macedonia came back under Yugoslav control, this time as part of the new Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, a new communist state replacing the kingdom of Yugoslavia. The region of Macedonia in Yugoslavia was formed into the People’s Republic of Macedonia, a constituent part of the larger Yugoslav federation.

The Greek government was very uncomfortable with this development. They were concerned that the communist dictator of Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito, had named the region Macedonia so as to bolster his claim to the parts of Macedonia under Greek control and that this would be a prelude to invasion.

Many Greeks who identify as Macedonian Greeks also believed that the Slavic inhabitants of the People’s Republic of Macedonia had unjustly appropriated their ancient culture and symbols by taking the name and symbolism of Macedonia. The Slavic Macedonians counter that the Macedonians were not Greek, that Northen Macedonia had not been Greek for a long time and that the Greeks have no monopoly on the cultural heritage of the region.

Tensions quietly simmered for decades until, in 1991, the former People’s Republic of Macedonia declared independence from the collapsing Yugoslav federation, changing its name to the Republic of Macedonia.

This provoked outrage in Greek Macedonia where in 1992 a million Greeks marched in a ‘Rally for Macedonia’ demanding that the new country to their north could not call itself Macedonia. Later in 1992 all major Greek political parties agreed that they would never accept any name that included Macedonia for their northern neighbour.

In all international bodies that Greece was a part of, the Greeks worked to ensure that no country called Macedonia would be accepted into those bodies under that name. Some countries recognised the new Republic as the Republic of Macedonia, namely Bulgaria, Turkey, Slovenia, Croatia, Belarus, and Lithuania, but most went silent on the question.

In 1992, the IMF, World Bank and other international organisations agreed to compromise on the name by calling the new country the ‘former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’. This compromise was initially rejected by both Greece and Macedonia and held up Macedonian entrance into the United Nations in 1993. In the end, after pressure from NATO on both countries, the new country was admitted into the UN as the ‘former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia’. NATO was eager to get this problem resolved as it was becoming increasingly concerned by the war brought on by the collapse of Yugoslavia and wanted to prevent it spreading to Macedonia.

Many Greeks remained outraged by this compromise and saw it as a betrayal by the United States and their NATO allies. In 1994 Greece demanded Macedonia change its name and imposed a trade embargo on the country for 18 months. In 1995 the two countries reached a new settlement which saw the Macedonians remove the Vergina Sun, a symbol of ancient Macedon, from their flag as well as any clauses in its constitution which could be used as a pretext to claim Greek territory.

There was a stalemate between the two countries, with the world divided between the two names for the republic until 2018. In 2018, the two countries finally signed the Prespa agreement in terms of which they agreed that the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia would be referred to as the Republic of North Macedonia by both sides.

The also deal includes recognition of the Macedonian language in the United Nations, and there is an explicit clarification that the citizens of the country are not related to the ancient Macedonians.

The treaty was narrowly approved in Greece and had significant opposition in Macedonia, but for the time being it seems to have finally resolved the conflict between both nations.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend