In recent weeks the government has seemed to be finding new resolve to deal with the deep problems in the public service.

There is certainly recognition that the country has a big problem with a bloated and inefficient civil service. As with its other challenges, the ANC will need an iron will to deal with public sector employees.

Last week President Cyril Ramaphosa said there was a draft plan ‘to build a state that better serves our people, that is insulated from undue political interference, and where appointments are made on merit’. The draft ‘National Implementation Framework towards Professionalisation of the Public Service’ includes proposals to depoliticise the public service and for competency assessments.

In last month’s Budget, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni maintained the promise he made last year to reduce growth in the public service wage bill by going back on wage agreements covering three years to reduce debt. There are plans to do away with annual cost-of-living adjustments and to reduce numbers through early retirement and the abolition of non-critical posts. But compensation is still expected to grow by 2.1 percent this year, and by 1.2 percent over the next three.

Whether or not the country can emerge from its current fiscal mess heavily depends on cutting the public service wage bill at all levels of government – national, provincial, and local.

Commentator Moeletsi Mbeki has long argued that in the hands of South Africa’s new political elite the state has been used to satisfy pent-up consumption demands, which has resulted in a very large public service. It is also a highly paid public service in which, unusually by international standards, the average wage is above that in the private sector.

The German sociologist, Max Weber, said a ‘rational state’ – a meritocracy governed by strict rules – was key to advancement into modernity. Our state has yet to be fully taken into the modern era.

Politicised public service

The politicised public service in South Africa raises questions about what would happen in the event of the ANC being replaced at the polls.

The Ramaphosa government could be in for an epic battle with the ANC’s union allies over its wage freeze and its goal of taking the political fangs out of the public service.

On the wage freeze, government’s position has been immensely helped by the decision of the Labour Appeals Court late last year, but challenges are growing from the unions. That the judicial system acted as the arbiter on this matter says much for the role of the judiciary in defusing what would otherwise have been a prolonged crisis, with rolling strikes. In a historical decision the court accepted the government’s argument that the original wage agreement was unlawful, as funding its implementation was not confirmed. But the unions are intent on breaking the freeze and have asked for a rise of four percent over the consumer price inflation rate.

The Treasury’s debt stabilisation programme is heavily contingent on the wage freeze. At national level, the public sector wage bill made up 34 percent of government spending in 2019/20, which is extraordinarily high by international standards.

From 2006/07 and 2019/20, compensation was among the fastest-growing spending items, increasing well over the country’s economic growth rate. Public service compensation absorbed 41 per cent of government revenues in 2019/20 and 47 percent 2020/21. In effect this means that the country is having to borrow increasing amounts at rising rates to finance its payroll.

From 2010 to 2020 compensation in the entire government sector – national, provincial, and local – grew by nearly 16 percent, with pay in local government growing by 34 percent due to massive hiring.

Way out of line

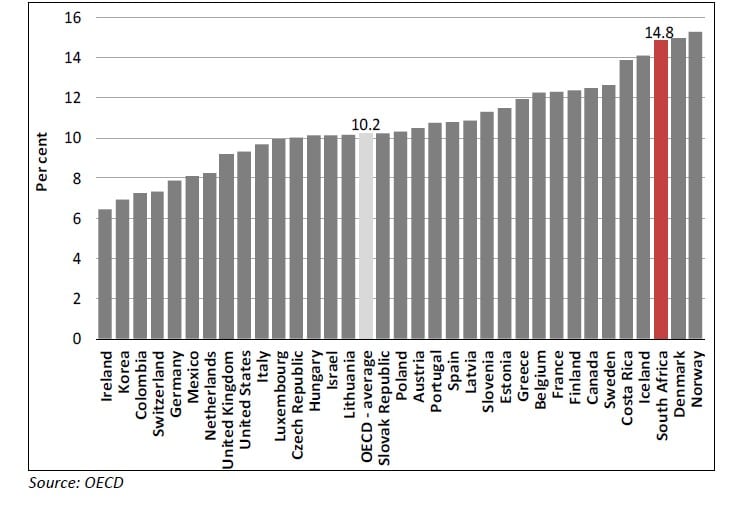

Today the public wage bill is way out of line with the size of our economy when compared to members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, a group which includes the world’s richest countries and the more wealthy emerging markets.

At 14.8 percent, South Africa’s ratio of general government compensation (all levels of government) to GDP is nearly five percentage points higher than that of the OECD average, as the chart below shows. It is close to that of Norway, Denmark, and Iceland and well above the ratio in the US and the UK.

A reduction of the ratio by five percentage points would imply a cut in remuneration, by something of the order of R250 billion. By comparison, the budgeted compensation for National Government this year is R170 billion. Faster economic growth would reduce the ratio, but with the country’s slow growth this alone can hardly be relied upon. Cuts in numbers and pay levels will be needed to reduce the compensation burden.

About 2.1 million people are on the public sector payroll at all levels of government. That is about 22 percent of the total number of people in formal employment. This number also includes those employed by extra-budgetary agencies like the Revenue Service as well as universities. The public sector is the bedrock of trade unions today and any attempt to dismantle what is a good deal for them has to bring on a wave of militancy and problems, given the sheer size of the sector.

Of the 2.1m public sector employees, about 455 000 are employed by national government, 1.1 million by provinces, 330 000 by local governments, 100 000 by extra budgetary institutions like the Revenue Service and the Road Accident Fund, and 110 000 by the universities and technikons. Over the past decade by far the fastest-growing component of public sector employment has been that of local government, which has risen by 34 percent. National government employment numbers have risen by 8.8 percent and that of provincial governments by 8.6 percent. There is little control over local government, which is collapsing in many parts of the country.

Cannot really be cut

About 400 000 public sector employees are teachers, 340 000 are doctors, nurses, and social workers, 190 000 are in the police service, and 75 000 are defence force members. That makes up just over one million employees – slightly more than half of the total public service – who provide basic state services and whose numbers cannot really be cut.

If the government is serious about debt stabilisation and getting public sector employment in line with international norms, wage cuts and layoffs are increasingly likely. A hiring freeze and natural attrition would help but it might take a long time to design and implement. To improve service quality, South Africa should consider introducing civil service exams, as is the case in France, India, and the US.

With the Covid-19 lockdown economic crisis, a number of countries have implemented wage cuts. Paraguay has implemented pay cuts of between ten and 20 percent for employees whose salaries exceed five and ten times the minimum wage. Uruguay is cutting the pay of better-paid officials and this is under consideration in other countries.

There is a strong case for pay cuts in a crisis, particularly when there have been high pay awards in the past. The cuts are temporary, and there is a case for equity in view of heavy lay-offs that have taken place in the private sector. Getting to grips with the runaway public sector payroll could turn out to be a very long battle.

[Image: Clker-Free-Vector-Images from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend