This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

25th March 1655 – Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, is discovered by Christiaan Huygens

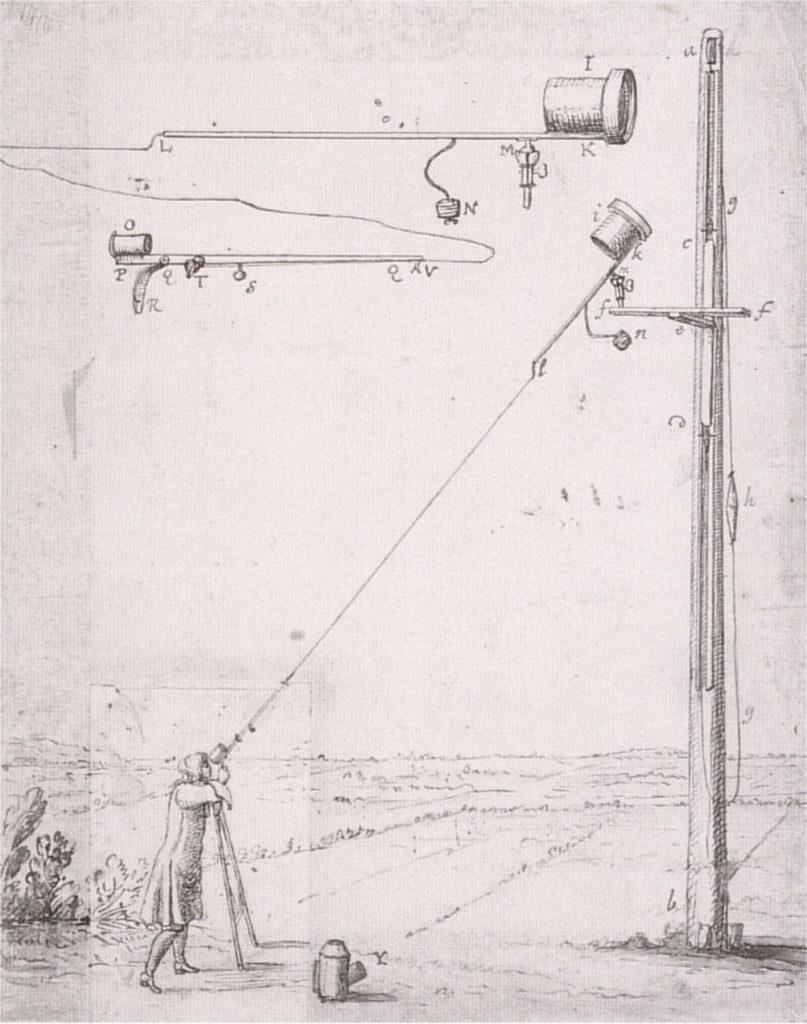

Inspired by the discovery of the moons of Jupiter by the Italian astronomer, Galileo, using an early telescope in 1610, the Dutch astronomer and scientist, Christiaan Huygens, decided to replicate Galileo’s experiments with his own telescope design.

Huygens had been building telescopes for some years when, in 1655 he designed a telescope that was superior to the one used by Galileo. When he pointed this at the planet Saturn (a planet known to the ancients, as it is observable by the naked eye), he noticed that it, like Jupiter, had objects orbiting it.

On 25 March he saw the largest of Saturn’s moons, Titan, which he creatively named Luna Saturni, Latin for Saturn’s moon. Titan was the 6th moon ever discovered and it is the solar system’s largest moon, being about 3.3 times larger than Earth’s moon.

28th March 1854 – Crimean War: France and Britain declare war on Russia

During the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire, which had dominated the Middle East and the Balkans for 300 years, was in serious decline. While the empire’s institutions decayed, many of the peoples it ruled over began to declare independence (events you can read more about in an earlier This week in history).

At the same time, the power of Russia was expanding. Having grown and developed as a European power over the past decades, Russia was aggressively expanding its territory across Europe and Asia to become the world’s largest land power.

These two forces were destined for a clash, and religion would prove to be the catalyst.

Russia, seeking to control and influence Turkey, used the issue of discrimination against the Ottoman’s Christian minority in the Holy Land as a reason to declare themselves Protectors of Eastern Christianity, and sought to advance the rights of Orthodox Christians in the Middle East and have all Christians in the Ottoman Empire placed under the protection of the Russian Tsar.

At the same time, the ambitious newly minted Emperor of France, Napoleon III, was seeking to shore up his domestic support, having turned France from a Republic into an Empire only a few years earlier. To do so he promoted the rights of Roman Catholics in the Middle East, especially their control over the holy sites of Christianity.

While the Ottomans and the Orthodox and Catholic churches managed to come to an agreement on the issues at play, the French and the Russians had invested too much prestige in the issue to back down. Napoleon was terrified that a loss of face on the issue would lead to a domestic revolt against him in France, and the Russians feared that if the Ottomans could disobey Russia, they would be a threat to Russian security, as they could block Russia’s access to the Mediterranean Sea.

In July of 1853 the Russians, seeking to scare the Ottomans into obedience, occupied the Ottoman vassal states in Romania. The French, and the British who were worried about Russian control of the Eastern Mediterranean threatening their hold on India, promised to support the Ottomans. So, in October 1853, the Ottoman Empire declared war on the Russian Empire.

While the Ottomans did well at first against the Russians, by the beginning of 1854 the French and British – fearing an Ottoman collapse – sent warships to support them. On 28 March 1854, France and Britain declared war on Russia.

In the months that followed, the Anglo-French forces sought to knock Russia out of the war by invading Russian-held Crimea and destroying the main Russian naval base at Sevastopol. This is why the war is today known as the Crimean War.

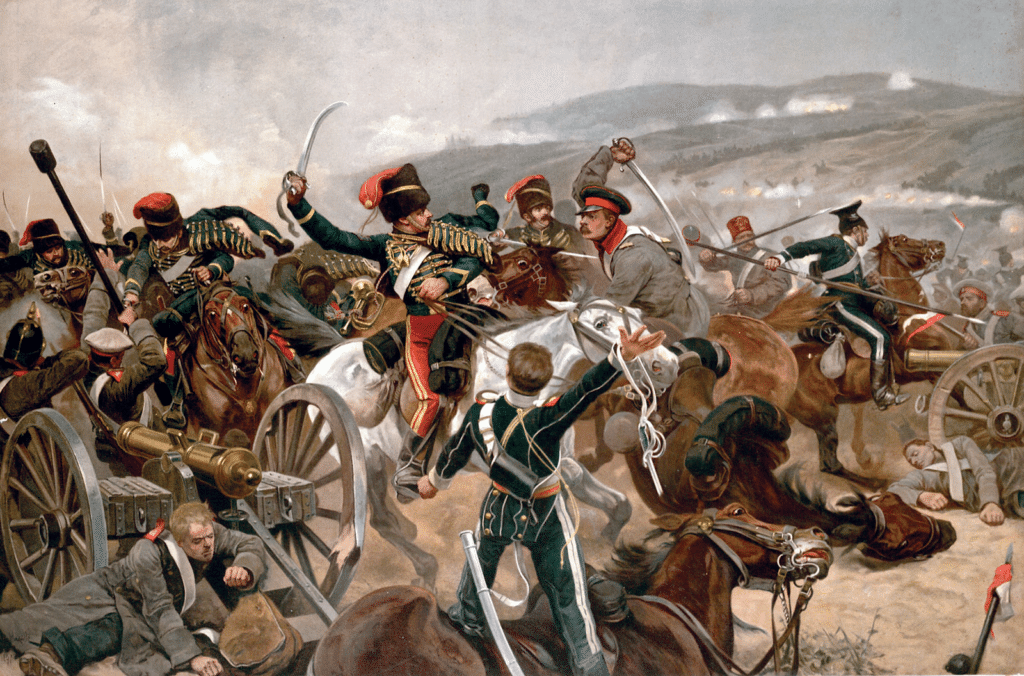

During the siege of Sevastopol, the fierce engagements of the Battle of Balaclava and the Battle of the Alma were fought, which saw great carnage on both sides – most famously the doomed charge of the Light Brigade.

Sevastopol would eventually be captured by the allied forces and, by 1856, the war would end in defeat for Russia, with all sides exhausted by the fighting. Russia would take decades to recover from the damage and humiliation suffered in the war, and the defeat paved the way for greater reform and modernization in the Russian Empire.

29th March 1879 – Anglo-Zulu War: Battle of Kambula: British forces defeat 20 000 Zulus

After the British defeat at the legendary Battle of Isandlwana, the northern-most column of British troops which had invaded Zululand from the north-west was ordered to cause a distraction to attempt to draw some of the Zulu strength away from the other British positions which were now in disarray due to the defeat at Isandlwana.

Attempting to draw off a force of 20 000 Zulu who were advancing towards vulnerable British positions, the commander of the northern column, Evelyn Wood, took a force of a few hundred cavalry ahead of his main force to raid some Zulu cattle herds, and then retreat to his main force which was fortified nearby.

To his surprise, as the British arrived to steal the cattle, they encountered the Zulu force of 20 000 which they thought was still a day’s march away. In panic, the British attempted to retreat, but due to the difficult terrain and speed of the enemy many were caught by the Zulus and killed. Some 225 of the 675 troops sent on the raid were killed and eight wounded, the survivors fleeing back to their main camp at Kambula.

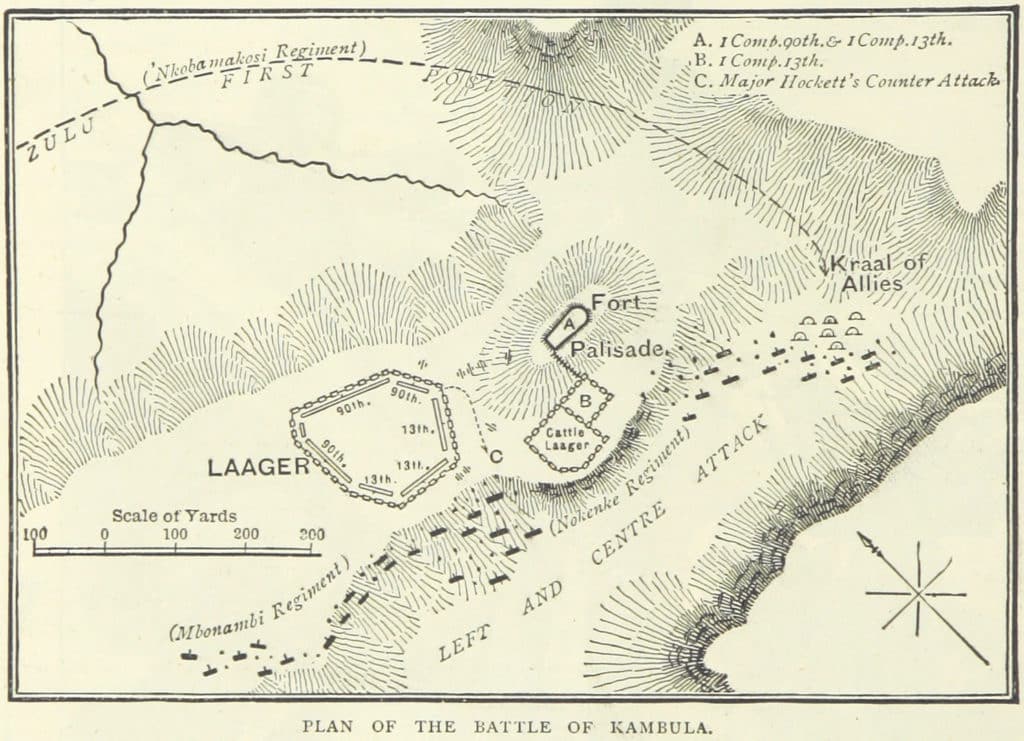

The next day, 29 March 1879, the force at Kambula were fortified and drew their wagons into a laager. They consisted of about 2 086 British and colonial troops and 180 African auxiliary troops. They had six cannons. Opposing them was a force of 21 000 Zulu warriors, some of whom had been at the Battle of Isandlwana, and were equipped with rifles looted from the British force there. Others were equipped with muskets and other older firearms which the Zulu warriors had purchased before the war.

The Zulu king, Cetshwayo, had specifically ordered his force not to engage the British in a fortified position but instead draw them out by moving to invade the Transvaal, which would force the British to confront them.

Overconfident, the Zulu commander, Mnyamana, decided to attack the British force and hoping to destroy it completely and open the Transvaal to raids while throwing the British invasion into even more chaos. He began to encircle the British force using the familiar ‘horns of the Buffalo’ tactic the Zulu were famous for.

The British sent out a force of cavalry to intercept the right horn of the Zulu force. The British rode forward and dismounted, firing into the Zulu ranks; the Zulu charged towards them, allegedly shouting ‘Don’t run away, Johnnie! We want to speak to you’. The British cavalry fell back and took up positions in the fortified area.

Intense fighting followed as the Zulu attempted to break into the fortified position. At one point, aided by the rifle fire of their comrades, a group of Zulus captured part of the British force, but were soon driven out again by a British bayonet charge.

By the late afternoon, the constant fire from the British fort and cannons had sapped the morale of the Zulu, who began to withdraw. The British sallied forth with their cavalry and tore into the Zulu forces, killing many of them. The pursuit was particularly brutal, as it was these cavalry who had been mauled so viciously the previous day by the Zulu, one of their commanders being likened to ‘a tiger drunk with blood’.

After the Zulu had retreated, the British infantry and their African allies moved out into the field and killed all of the wounded and those they found hiding in the area. As many as 2 000 Zulus were killed in the battle for the loss of only 29 British troops.

The battle destroyed Zulu morale for the rest of the war and their forces would never again attack fortified British positions with such bravery.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend