This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

1st April 1939 – Spanish Civil War: Generalísimo Francisco Franco of the Spanish State announces the end of the Spanish Civil War, when the last of the Republican forces surrender

By 1936, Spain had endured a century of turmoil and internal division driven in part by disputes over the role of the church, the role of the king, the power of the aristocracy and the power of the army.

Many of these issues can be traced back to the 1812 attempt by the Spanish Liberals to reform the Constitution to limit the power of the king; these reforms were overturned later, and the king dissolved the Constitution. Decades of instability followed the 1812 reforms and there were 12 successful coups between 1814 and 1874.

Also, during this period, a dispute over the succession and the power of the church in Spain led to the rise of the Carlist movement, which sought to restore the snubbed Prince Carlos to the throne which the Carlists believed he was unfairly denied.

The group was strongly traditionalist and was supported by both rich and poor Spaniards who sought to protect the power of the monarch and the church in Spain. The Carlists began three wars between 1833 and 1876, in all of which they failed to achieve their aims. By 1936 this movement was still very much alive.

In 1873, King Amadeo I, abdicated from his throne after a turbulent reign where he was unable to deal with rebellions in Cuba and by the Carlists.

The Republicans in Spain decided to declare Spain a republic after his abdication and created the First Spanish republic. With a year, General Arsenio Martínez Campos overthrew the new republic, which had been bitterly divided between centralists and federalists, and restored the monarchy.

Initially the restoration of the monarchy provided some stability, and the economy grew, seeing Spain beginning to industrialise. However, the country remained weak and divided. In 1898, provoked by ongoing rebellions in its Cuban colony, the United States declared war on Spain and in the following Spanish-American War, Spain would lose its remaining colonies, such as Cuba and the Philippines. This greatly damaged the prestige of the government and the monarchy and reignited old divisions. A troubled military campaign in 1909 against Morocco only worsened this problem.

The growing industrialisation of Spain had also seen the rise of powerful socialist and anarcho-syndicalist movements and trade unions which, being staunchly anti-monarchist, anti-church and anti-aristocracy, also challenged the power of the monarchy.

With growing discontent with the monarchy and the strengthening of the socialists in the cities, the army and other anti-socialist establishments feared a communist revolution.

Thus, in 1923, Miguel Primo de Rivera, Captain General of Catalonia, carried out a coup against the parliament, blaming Spain’s problems on the parliamentary system. He was supported by the king Alfonso XIII. He assumed total power and ruled Spain as a dictator until 1930.

Primo de Rivera’s regime did not last very long; in an attempt to build his support he spent recklessly on handouts to business as well as investing massively in public services and drove the country into bankruptcy.

By 1930 the army no longer supported him and, in January that year, the king, fearing De Rivera’s unpopularity would destroy the monarchy, removed his support and forced him to resign.

The king attempted to get several generals to take the place of the resigned dictator and slowly move the country back towards a constitutional monarchy, but these efforts came too late and the newly appointed dictator, Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar, called local elections to appease the republicans and socialists and the monarchist parties, while still managing to win more votes overall, suffered serious setbacks in the cities. Riots followed the election, with demonstrators demanding the removal of the king. The army said it would not protect the king, so he fled the country.

On 14 April 1931, the Second Spanish Republic was declared, and a new Constitution was drafted. The provisional government which sought to draft the new Constitution was dominated by radical and socialist parties. These parties feared that they would lose an election and so delayed holding any ballot until 1933. During this time the Catholic Jesuit order was banned and had all their property expropriated, the army was reduced, and major landowners had their property expropriated.

The prime minister at the time, Manuel Azaña, called for a confidence vote to secure his support, but two thirds of his party abstained. The president forced Azaña’s resignation and elections were called for 1933.

The Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA), a political party made up of traditionalists, fascists, Carlists and monarchists, won the election, along with their allies. According to Wikipedia, ‘parties of the right won around 3 365 700 votes, parties of the centre 2 051 500 votes, and parties of the left 3 118 000, according to one estimate’.

President Alcalá-Zamora, who had also been the republic’s first prime minister, refused to invite the new right-wing parties to form a government as he feared they would restore the monarchy. Instead, he invited the second largest party, the Radical

Republicans, to form a government, and managed to keep CEDA out of cabinet positions for the next year.

Between 1931 and 1936, however, crises continued to plague Spain as groups on both right and left rose up against the government – or, in the case of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) a large federation of anarcho-syndicalist trade unions, endlessly called for strikes against the government.

In 1934 the non-anarchist socialists rose up against the government and murdered many policemen in parts of the country. The rebellion was crushed in two weeks by the navy and army. There were reversals of the land reforms and expropriations of 1931-1933 in this period and many of the returning landlords and employers took the opportunity to exact revenge on leftist workers and peasants.

The president, seeking to collapse the right-wing government, called an election at the end of 1935. In January 1936, Manuel Azaña, who had been accused of being involved in the 1934 uprising and who had been imprisoned for a year because of this, organized a coalition party of all the parties of the political left.

Azaña was obsessed with the threat to the republic from the political right and so sought to build a united front against them by uniting the left and fusing all the parties from moderate republicans to hard-line communists into the new ‘Popular Front’.

The election was held in February 1936 and the Popular Front won a narrow victory over CEDA. The election was marred by political violence, and some historians believe it may have been fraudulent. Right-wing parties believed their opponents were no longer playing by the rules and so sought to destroy the republic.

The radical left of Azaña’s Popular Front began making speeches about how they were going to turn Spain into a socialist republic in association with the Soviet Union and one trade unionist declared ‘the organized proletariat will carry everything before it and destroy everything until we reach our goal’. Even some socialists were horrified by the violence in the election and the general chaos engulfing the country.

At this point violent conflicts between right-wing and left-wing groups was a daily occurrence with arson and violence carried out against homes, churches and schools. Polarisation was intense and moderates on both sides were forced into the arms of extremists to seek protection from the violent mobs of the other side. Workers began to steal from shops, peasants began to invade land and the army began to plot.

In the immediate aftermath of the election, right-wing officers and military commanders began meeting about carrying out a coup against the new government. On hearing of this, the new government attempted to reduce the coup’s power by moving the generals suspected of involvement to different posts in out of the way places. The plotters were from a variety of political backgrounds and were not coherent ideologically, consisting as they did of fascists, traditionalists, monarchists and Carlists. The main objective of the plotters was to place the army at the centre of the Spanish state and ensure its dominance in government going forward.

A fascist murder of a socialist police officer in Madrid on 12 July 1936 set off a wave of violence between left and right. In this violence a prominent monarchist was assassinated as revenge, the involvement of the police in this murder providing the excuse for the army to launch their coup.

The coup was planned for 18 July 1936, but when the plot was uncovered a day before, the plan was launched immediately. The core of the coup’s forces was the mostly Moroccan ‘Army of Africa’, which was stationed in Spanish-controlled Morocco. The coup failed to capture any major cities except the southern city of Seville, which allowed the Army of Africa to land in support of the coup.

The socialists, anarchists and communists hastily began arming themselves to fight the coup and soon had formed armed groups. Around 60% of the army joined the coup as well as many police and traditionalists in the north of the country. However the government and its allies maintained control over most of the major cities and the east of the country.

The coup attempts soon turned into a full blown civil war, which raged across Spain, the army and its right-wing supporters calling themselves the ‘Nationalists’ or ‘True Spaniards’ while their opponents called themselves ‘The Popular Front’, ‘The Government’, or the ‘Republicans’. Separatist movements in Basque country, Catalonia and Galicia also joined the conflict mainly on the Republican side, seeking autonomy or independence for their regions.

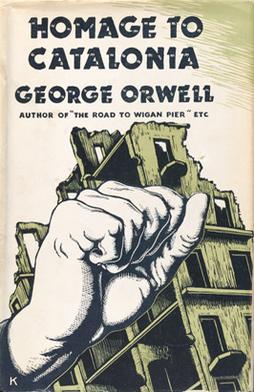

International support soon flowed to the two sides with the Soviet Union and Mexico supporting the Republicans and the Fascist nations of Italy and Nazi Germany as well as Portugal supporting the Nationalists. International volunteers also flocked to join the fight mostly on the Republican side, famously including author George Orwell, who wrote a book about his experience.

The war saw both sides carry out atrocities against the civilian population and hundreds of thousands were killed. Historian Michael Seidman stated that the Nationalists killed approximately 130 000 people and the Republicans approximately 50 000 people – but there is no real consensus on the casualty figures.

A general called Francisco Franco was not the leader of the initial coup, but soon came to control the Nationalist side of the war and effectively fused its many feuding factions into a united party called the ‘Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista’ (FET y de las JONS).

The Republicans were plagued by infighting and internal division. As they became increasingly became dependent on Soviet aid, the Stalinist faction of the Republicans came to dominate.

The war inspired many writers and intellectuals and many influential socialists journeyed to fight in the conflict. Some have called the war, a ‘dress rehearsal’ for the Second World War and the first fight against fascism.

The war slowly turned against the Republicans and the Nationalists cut their holdings into two pieces by July 1938.

Finally on 1 April 1939, the Nationalists declared victory as the last Republican troops surrendered. More than 500 000 people fled to France in the aftermath and the Nationalists carried out numerous violent reprisals against and executions of the losers. Around half a million people died in the conflict and Franco would establish himself as dictator of Spain until his death in 1975.

Franco restored the monarchy in 1947, but did not appoint a monarch.

In 1969 he finally appointed Juan Carlos as Prince of Spain and his successor (not a Carlist candidate) for the throne. Carlos would see the authoritarian state dismantled and a return to constitutional monarchy.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend