This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

10th April 428 – Nestorius becomes the Patriarch of Constantinople. Three years later, he would be deposed due to alleged heresy

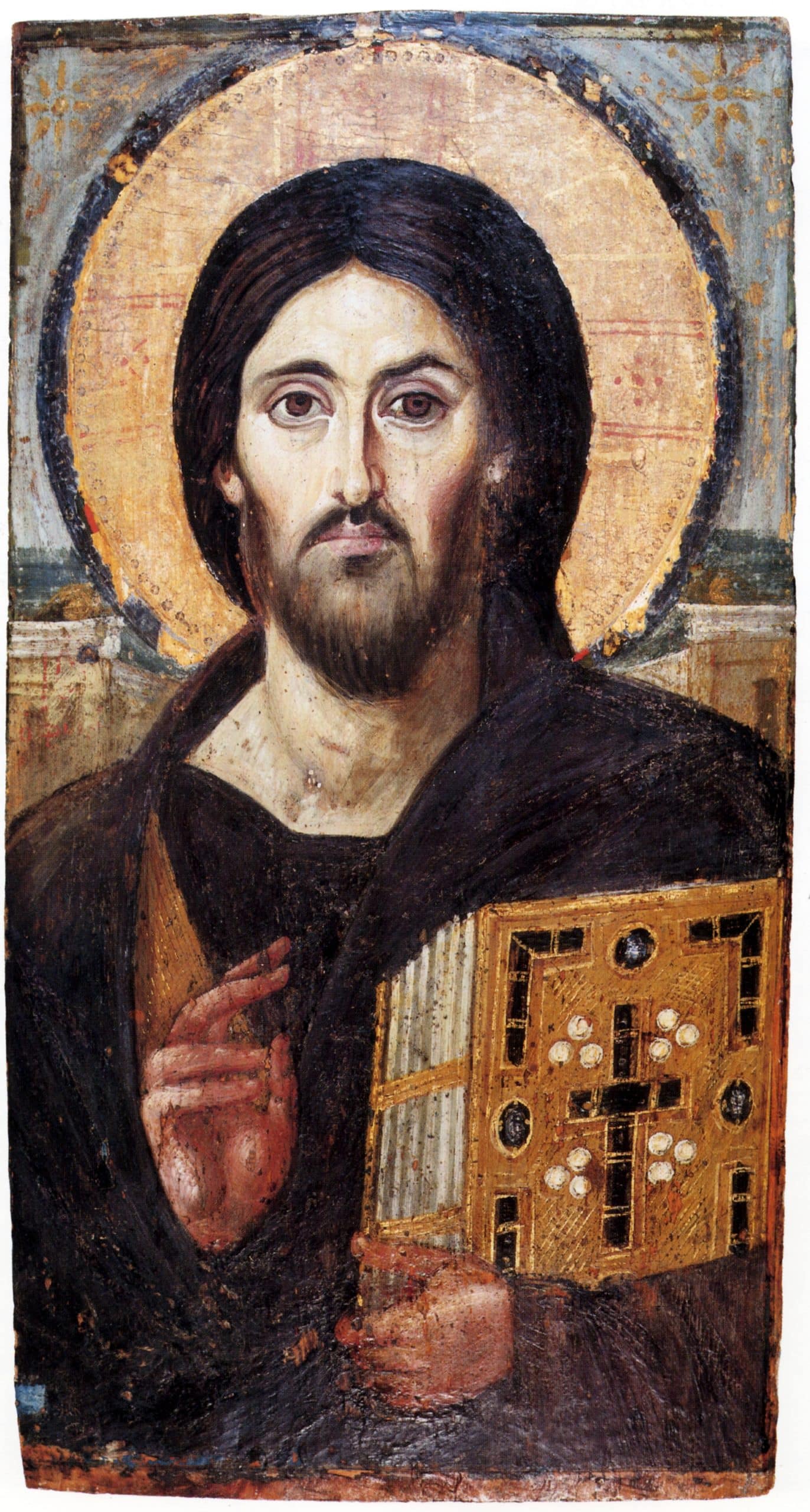

The early Christian Church was continuously embroiled in theological disputes in the centuries after its legalisation by the Roman emperor Constantine in 313 A.D.

Many of the disputes were concerned with the theology of the precise relationship between Christ and God. Often these disputes would be adopted by groups along language or political lines or by the clergy of one of the big cities of Christendom.

During this period, the five biggest cities of Christianity and their bishops tended to hold sway over church politics. These cities were Constantinople, Rome, Antioch (in modern southern Turkey), Jerusalem and Alexandria (in Egypt).

Each of these cities was also the main bishopric which, roughly speaking, represented each of the different linguistic groups in the Roman Empire. The Roman bishop represented the Latin peoples, the Constantinople bishop the Greeks, Antioch and Jerusalem the Syriac-speaking peoples and Alexandria the Coptic Egyptians. This is a gross oversimplification, but helps to explain some of the reasons why these issues took on such political significance.

One of the most important of these early disputes was the doctrine of a of a bishop of Alexandria called Arius, who taught that Christ is distinct from and subordinate to God the Father rather than co-eternal with the Father as modern Christians believe, and also distinct from the Father in violation of the modern Christian view of the holy Trinity. This view was extremely controversial, and Christianity was split between the followers of Arius and his opponents.

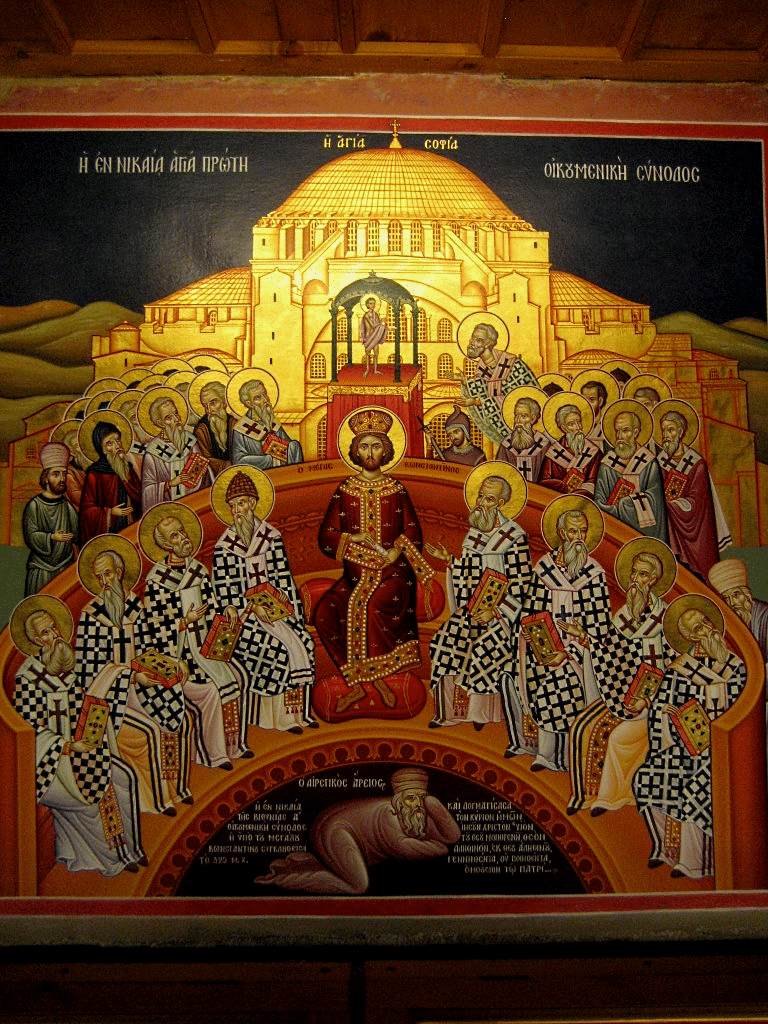

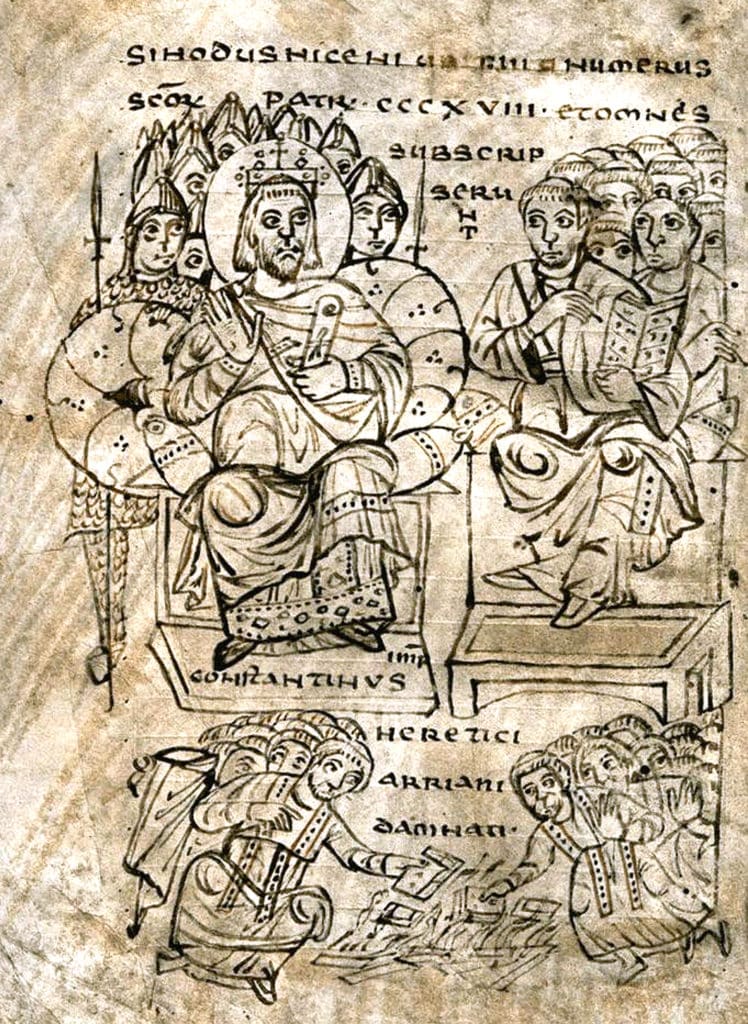

The dispute got so bad that the Emperor Constantine convened the First Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D. which sought to end the dispute once and for all. With numerous bishops from across the Christian world in attendance, after much discussion the council finally decided on a statement of belief which it believed the whole Christian world should adopt.

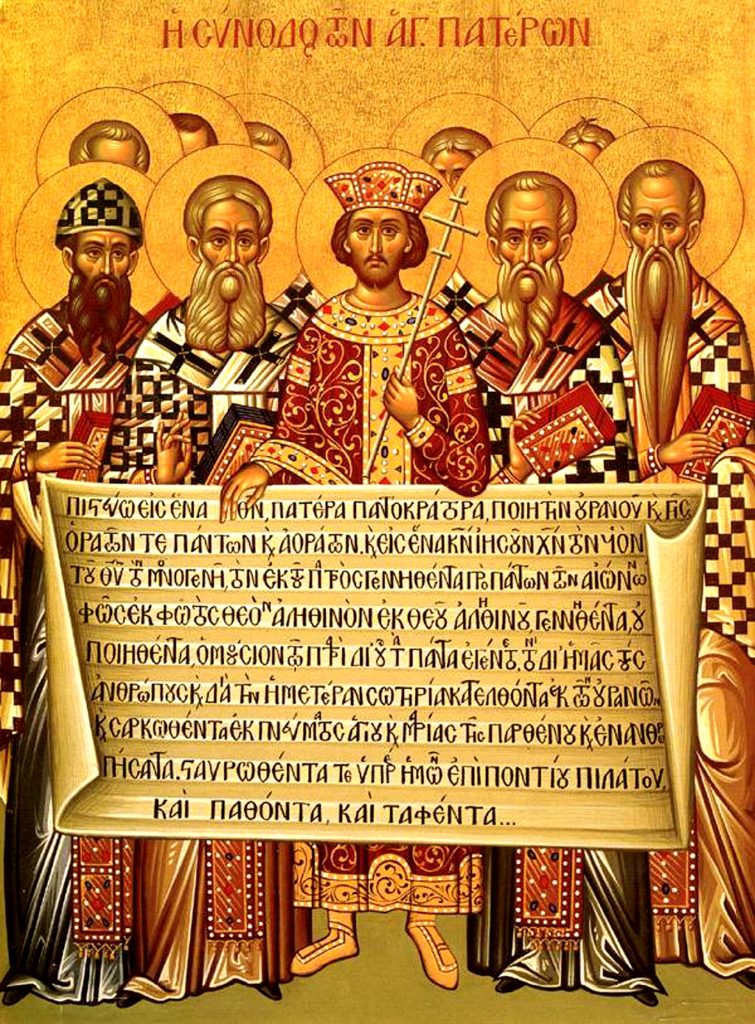

This statement, today known as the Nicene Creed, read as follows:

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father [the only-begotten; that is, of the essence of the Father, God of God,] Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father; By whom all things were made [both in heaven and on earth]; Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down and was incarnate and was made man; He suffered, and the third day he rose again, ascended into heaven; From thence he shall come to judge the quick and the dead. And in the Holy Ghost. [But those who say: ‘There was a time when he was not;’ and ‘He was not before he was made;’ and ‘He was made out of nothing,’ or ‘He is of another substance’ or ‘essence,’ or ‘The Son of God is created,’ or ‘changeable,’ or ‘alterable’— they are condemned by the holy catholic and apostolic Church.]

The final lines were a very direct rebuke of the Arian creed and so Arian belief was outlawed in the Roman Empire and state authorities in many regions persecuted Arian Christians.

Arian churchmen did not give up the fight easily, and sent many preachers to the Germanic tribes living outside the Roman Empire. These peoples, such as the Goths and the Vandals, soon became Arian Christians and when they later invaded the western half of the Roman Empire, they would repay the persecution of their forebears on the Orthodox Church authorities. Arianism would continue to be the main branch of Christianity practised by the rulers of Western Europe until the 6th and 7th Centuries when the Roman church managed to convert them to Nicene Christianity.

While the church in Western Europe and North Africa was torn apart by the conflict with Arian Christianity, the Church in the East was about to face a new schism.

In the early 5th century, the theologians of the Syriac-speaking schools in Antioch, began teaching a doctrine that would later come to be known as Nestorianism.

This theological position came to hold that Christ had a human and divine side and that these two ‘natures’ were not unified, as orthodox teaching held, but rather distinct. So, by this position, Mary cannot be called the ‘Mother of God’, as she gave birth to the human aspect of Jesus, not the divine one. This goes against a fundamental tenant of Orthodox Christianity, namely that God died on the cross for the sins of humanity. In particular, this position was offensive to the Greek-speaking clergy who dominated the Eastern Church in Constantinople.

Unfortunately, we do not know much about the early Nestorians, their beliefs or the bishop for whom their creed is known in the West, the Bishop Nestorius, as most of the accounts of their early history were written by Orthodox scholars and so are deeply hostile and some of it may be exaggerated or made up.

What we do know is that a bishop called Nestorius became head of the Bishopric of Constantinople on 10 April 428 AD. While it is not known if he was a Nestorian, ironically enough, we do know that after attempts to mediate between the Nestorians and the Orthodox failed he was attacked by a clergyman called Cyril of Alexandria, who denounced him as a heretic.

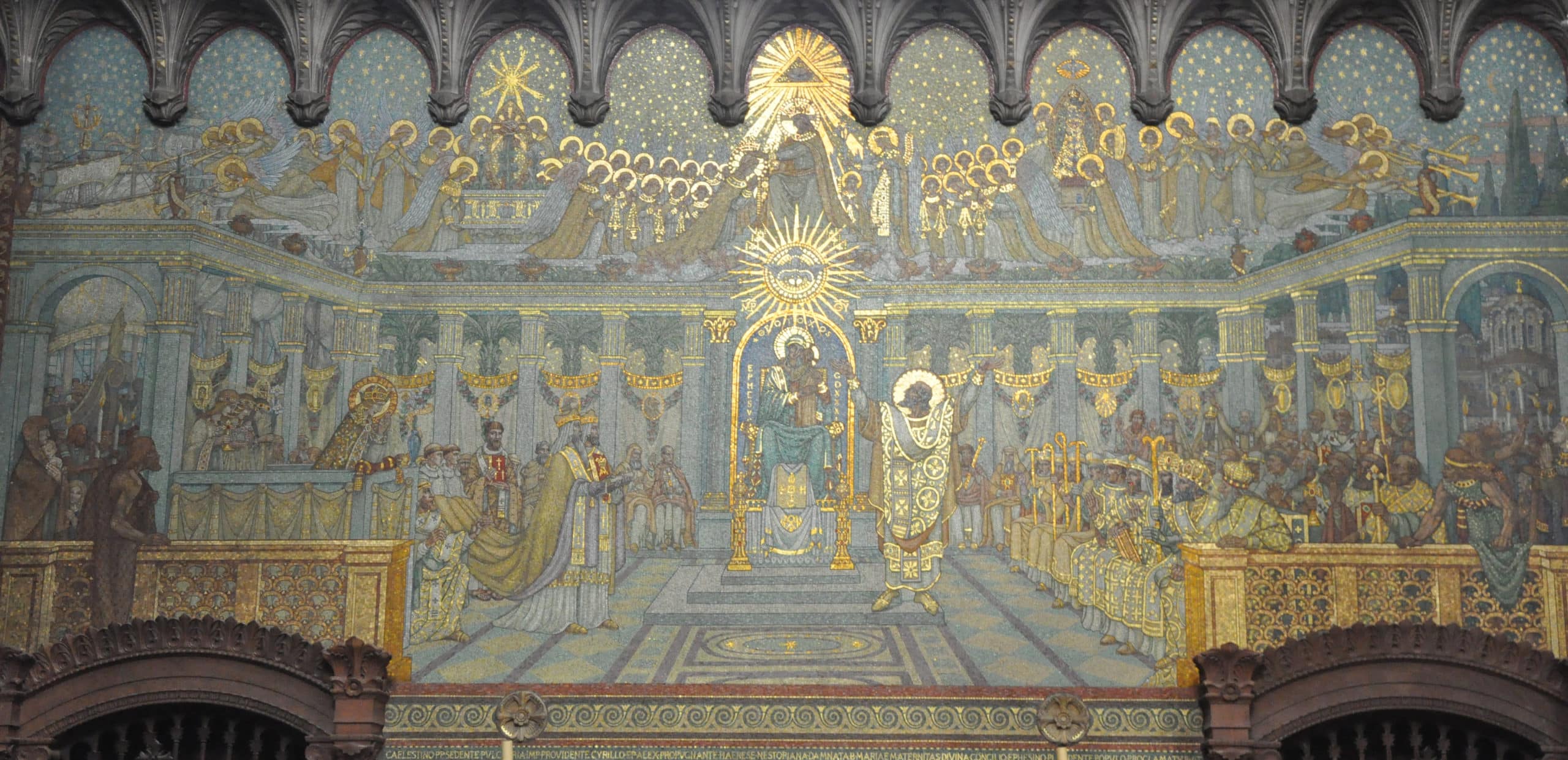

The Emperor of the Romans, Theodosius II, supported Nestorius, but much of the Greek clergy of Constantinople disliked the foreigner Nestorius who was from Antioch. The anti-Nestorius faction managed to win the support of the Bishop of Rome and, at the Council of Ephesus held in 431 AD – which the emperor had called to try and end the dispute – the Anti-Nestorians passed a resolution which saw Nestorius condemned as a heretic and kicked him out of his position as the head of the Church of Constantinople.

Following this, the Nestorian Christians would for the most part be driven from the empire, and many flocked to the Christian communities in the Persian Empire, which was the great enemy of the Romans and encouraged division in the Christian communities. The Persian church would soon declare independence from the rest of Christendom and became known as the Church of the East. The successors of the Church of the East continued to spread their variant of Christianity throughout Asia, establishing Churches in Iran, India, China and even converting many Mongols, including one of the Khans, to Nestorian Christianity. The conflict between Eastern Christians and the Catholic and Orthodox churches only saw official resolution in the 1990s.

To non-Christians, and even to modern Christians, many of these disputes may seem overly theological, esoteric or arcane. However, evidence suggests that the general population at least in the cities was passionately involved in these disputes. Preachers for each creed could start riots for or against their position, local opponents of a bishop might embrace the alternative position to undermine their bishop. Supporters of different creeds would chant their positions at sporting events and theology might be debated in the marketplaces and streets.

It is also worth remembering that in the early Middle Ages, not only was one’s religion often more central to one’s life and identity, but also religion was a fundamental building block of the community, the local church provided charity, it organized events, it managed marriages, it helped solve family disputes and so a divided church would mean a divided community. It was for this reason that state authorities were quick to crush alternative churches as they were seen as a threat to the society as a whole.

11th April 1909 – The city of Tel Aviv is founded

By the last decades of the 19th century, the Zionist movement had gained many supporters across Europe and many Jews were inspired by its ideas to begin moving to their ancestral homeland in the Middle East, what was once the Kingdoms of Israel and Judea but, after the failure of one of the Jewish revolts, was renamed Palestine by the Romans.

The first major wave of this immigration was known as the First Aliyah, and when it began in 1881, many Jews from mostly Yemen and Eastern Europe migrated to the region seeking a better life, one hopefully free from the persecution they often encountered in their home countries. The area at the time was under the control of the Ottoman Empire, as part of Ottoman Syria. The Ottomans were a weak and declining power and only held the region lightly under their control. Many of these immigrants settled in already existent Jewish communities, but others settled in new settlements and some in Arab-dominated towns. All told, by 1903 – when immigration slowed down – approximately 25 000 to 35 000 Jews had migrated into the region. However, due to lack of funds and economic opportunity, many of these immigrants would leave within a few years and only around 6 000 remained.

Tensions which had long existed between the local Jewish communities and the local Arab communities often flared up as Jewish immigrants arrived, and the Ottomans sought to try reducing these tensions by restricting Jewish immigration and the purchase of land in the area by Jews. Ottoman control over their Arab provinces was weak and they feared sparking an Arab revolt. A second wave of migration began around 1904, which saw many Jews, mainly from the Russian Empire, leave for America and South Africa, and a small number came to Palestine.

A Jewish urban community organisation was formed in 1906 consisting of Jews from the region and immigrants and sought to create a Jewish town near the ancient city of Jaffa, which was where they currently lived. With the help of a Dutch citizen called Jacobus Kann, the Jews circumvented the Ottoman restrictions on buying land by Jews and on 11 April 1909, marked out 60 plots on the site of what would become the city of Tel Aviv.

These were allocated to Jewish families by using grey and white seashells to match the name of a family with a plot number. And so the city was founded.

The population grew quickly and by 1915 the town had an estimated population of 2 679. However, things would be brought to a halt in 1917 when the Ottomans expelled the Jews of Jaffa and Tel Aviv because they feared they would support the invading British forces during the First World War. The expelled people returned to their homes in 1918 once the British gained control of the region as the British Mandate of Palestine. Tel Aviv was originally considered a suburb of Jaffa but its growth meant that by 1921 it received ‘township’ or local council status within the Jaffa Municipality. By 1922 the city had a population of 15 185 – 15 065 Jews, 78 Muslims and 42 Christians.

By the eve of Israel’s formation in 1948, the flight of refugees from Europe had swelled the city’s size to 230 000 people. When the region was first partitioned to form an Arab and Jewish state, the Partition had Tel Aviv on one side and Jaffa on the other. After the First Jewish-Arab War, Jaffa was captured by the Israelis and most of its Arab population fled. Tel Aviv would be the temporary centre of Israeli governance until 1949 when it was moved to Jerusalem.

Today the city has a population of over 460 600, and it is the economic and technological centre of Israel.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend