This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

26th April 1986 – The Chernobyl disaster occurs in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Some have claimed that the day the Soviet Union died was the day of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. It’s not difficult to see why; the disaster, which remains far and away the worst nuclear disaster in history, was caused as much by the system of Soviet communism as it was by the technicians on duty at the Chernobyl power plant on the night of 26 April 1986.

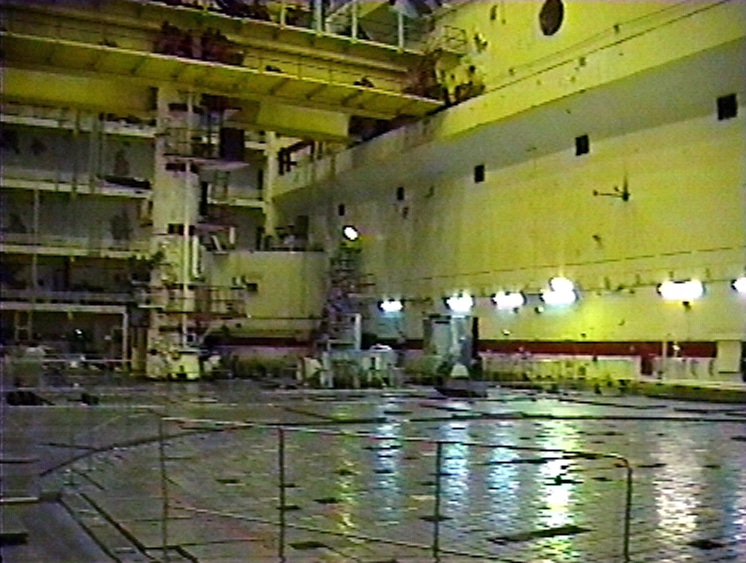

Beginning in 1972, the construction of the Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant was meant to show the power and technological prowess of the Soviet Union. The plant had four reactors which could each produce around 1000 MWs of electricity, which was around 10% of Ukraine’s needs in 1986. The plant also saw the construction of a town nearby called Pripyat, which was to house the workers and provide the services needed for the facility.

The Soviets planned to keep expanding the plant into the far future, with Reactor 1 coming online in 1977, reactor 2 in 1978, reactor 3 in 1981 and reactor 4 in 1983. Further reactors would be built near the first four, with the 12th expected to be completed around 2010.

The reactors were first- and second-generation RBMK-1000 reactors modelled after the Leningrad and Kursk reactors. RBMK is a Russian acronym which stands for ‘high-power channel-type reactor’, a kind of graphite-moderated nuclear reactor which used graphite to control the speed of a nuclear reaction rather than molten salt or water which are used in many other nuclear reactors. RBMK reactors were a product of Soviet manufacture and design and were massive in size for the time. They were also designed to be able to use natural uranium in their fuel rather than the more expensive enriched uranium that most reactors use for fuel. Unlike most nuclear reactors, RMBK reactors did not have a proper containment building over the reactors, as the design would have meant that a containment building would need to be huge, and so to save costs, most RMBK reactors were built without proper containment buildings.

Unfortunately, there were many other design flaws in RMBK reactors apart from just the lack of a containment building. These flaws made meltdowns much more likely, and this was made clear in a study by the Soviets in 1980. Seeking to save the Soviet state from embarrassment and extra expense, almost no major alterations were made to the designs to correct these flaws, the Soviet government settling instead for for simply updating the manuals.

This was not adequate, however, as Soviet engineers running the plants often didn’t follow the recommended procedures very closely as the demands for higher productivity from political superiors required them to fix problems on the fly and push equipment as hard as possible to meet quotas. Previous accidents were also not learned from, as these were covered up and protected as state secrets. Partial meltdowns at Chernobyl reactor one and the Leningrad reactor were kept so secret that there were not even known to other workers at those plants.

In the 1980s Soviet designers were hoping to test whether or not they could keep the water pumps (which pumped water over the reactor when it had been shut down) running with left-over steam from the reactor while the back-up generators powered up. The back-up generators needed around a minute to power-up, and during the time between a reactor shutting down and the generators fully kicking in, this meant it was a minute in which the reactor would be without cooling water.

If left-over turbine steam could be used to keep the pumps running during that minute, it would eliminate a serious danger without the need for major modifications to the reactor.

Soviet engineers at Chernobyl reactor tried unsuccessfully to test this theory on a working reactor, first in 1982, and again in 1984. They made small modifications each time and planned another test run for 25 April 1986, to coincide with a scheduled reactor shutdown.

The test was planned for 2.15pm on 25 April by the day shift of the plant, who had prepared for the experiment. However, the grid operator in Kiev asked that the shutdown be postponed to avoid a blackout, and so the test was not performed by the day shift. Instead, it was now scheduled to be performed around midnight, just as the evening shift was handing over to the night shift. The night shift only received this news late and had been expecting to run an almost completely shut down reactor.

Around midnight on 26 April, the planned reactor shutdown began. Power dropped far too quickly, however – to around 30 MW, far below the 1000 MW which the reactor produced at full power. The precise cause of this problem is unknown as the person operating this part of the reactor died shortly afterwards in hospital. It may have been due to equipment failure, a common occurrence in Soviet reactors, or human error on the part of an unprepared crew.

This 30MW level was far too low to conduct the planned test and so the power plant control room tried to raise power by overriding the automatic control of the graphite control rods (which slow the nuclear reaction) and lifting most of the control rods out of the reactor. The reactor became unstable at this point.

Eventually the reactor went back up to 200 MW, still far below the 700MW needed for the test –but the control room, fearing retribution for failing to carry out the test and hoping to secure bonuses for completing it, pressed on. Due to a design flaw in the RMBK reactors in this state, the reactor was primed for a runaway increase in power, and with the control rods removed and the cooling-water flow reduced by the low power level, there was little to slow down the reaction.

At 1.23am, the test went ahead. It is unclear what happened next, but a shutdown was ordered. It is not clear if this was an attempt to end the experiment or was the planned shutdown test. Due to another design fault (a feature intended to increase efficiency) the insertion of the control rods would initially speed up the reaction before it slowed it down; this proved disastrous, as the emergency shutdown would cause a spike in power.

This problem had been identified in an earlier Soviet test in 1983, but it was considered unlikely to occur again. The power spike caused part of the core to overheat and jam the control-rod mechanism which, in turn, prevented the reaction from slowing down. The reactor power spiked to ten times its normal output.

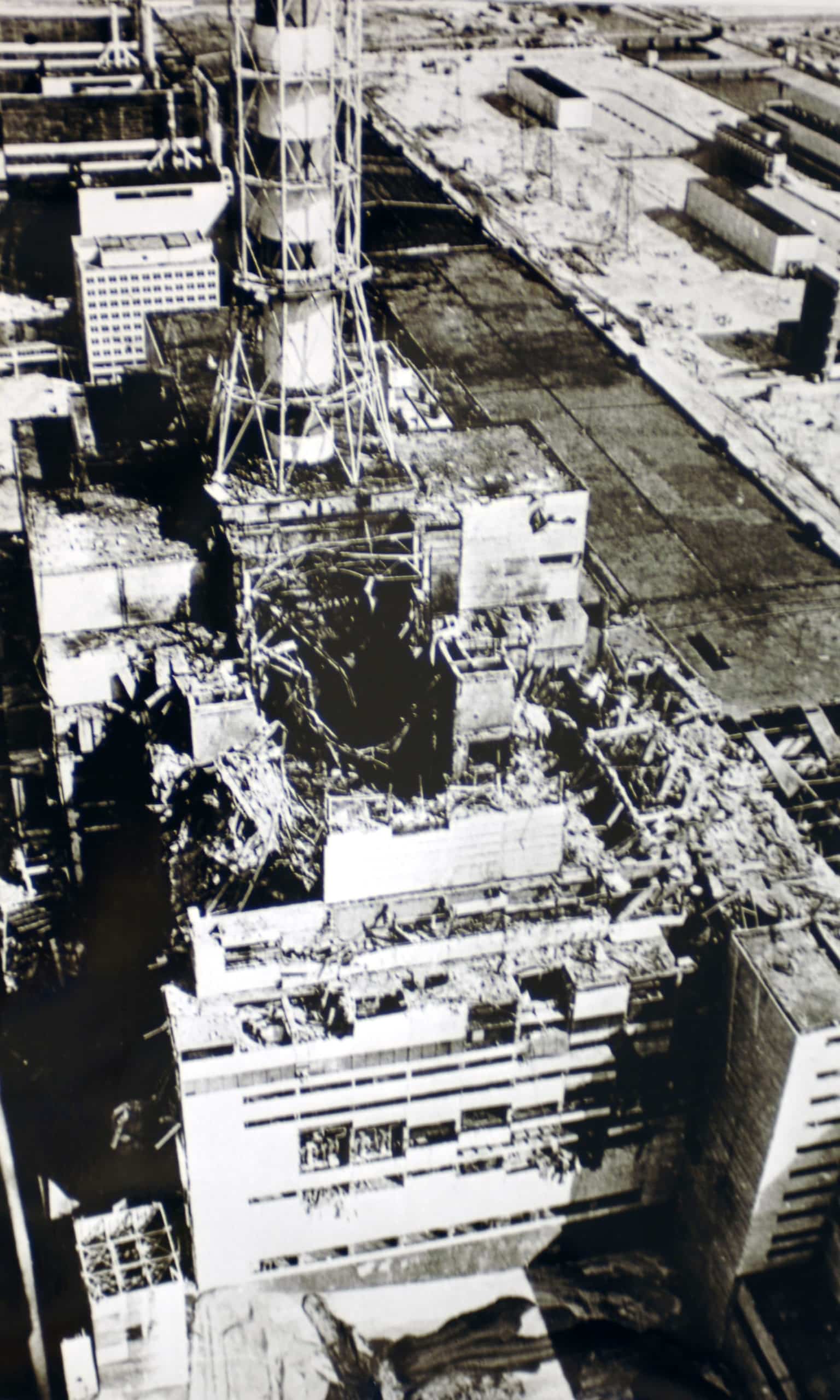

A series of explosions followed, which, in the absence of a sufficient containment building, shot huge amounts of radioactive materials into the air and started a fire. The local fire department was called but was not told that radioactive materials were present. Some suspected this was the case, but decided to fight the fire anyway so as to prevent it spreading to neighboring reactor 3, which was still running at full power.

Despite numerous reports of local residents experiencing the onset of acute radiation sickness, no evacuation was organized until 11am on 27 April. Residents were told that they would be evacuated for three days. The evacuation would turn out to be permanent. Eventually, 350 000 people would be evacuated from the area.

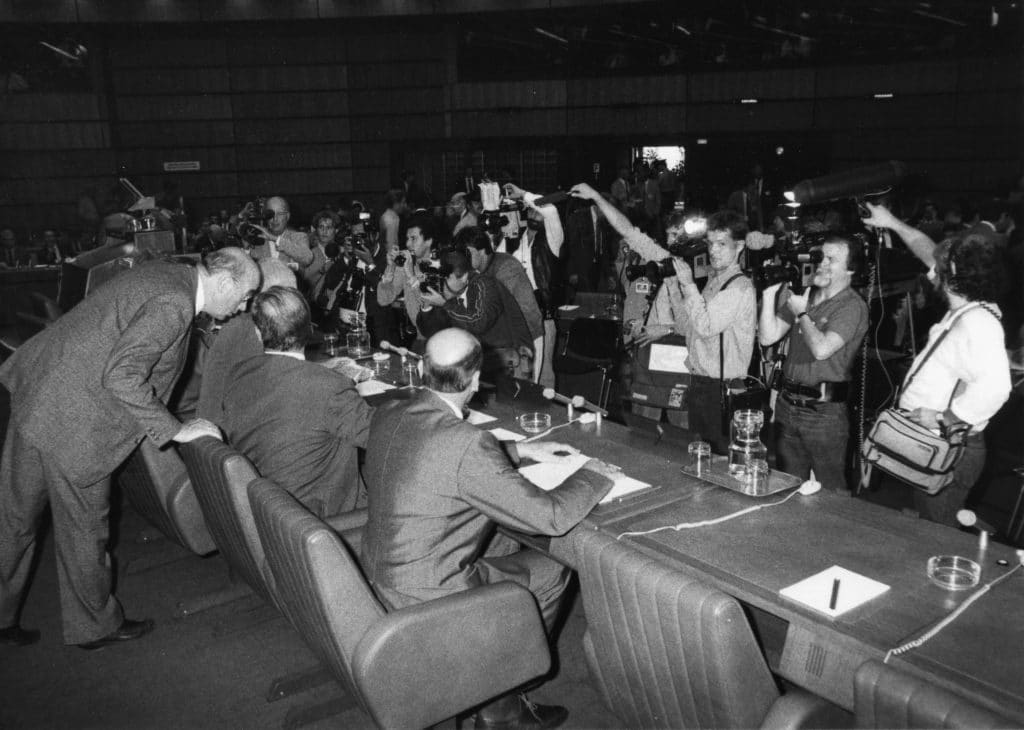

As the power plant was run from Moscow, the Soviet government of Ukraine was not told of the disaster until much later. The Soviets did not publicly acknowledge the disaster to the world and attempted a cover-up. However, the amount of radiation released was so great that it was detected by the safety systems at a Swedish nuclear plant on 28 April.

That evening the Soviet government officially acknowledged the accident – but only with a 20-second spot on the news, with the rest fo the programme dwelling on nuclear accidents in the West.

In the following weeks the Soviet government worked to contain the fallout, put out remaining fires and build a metal structure around the reactor to prevent further contamination. This involved the efforts of tens of thousands of ‘liquidators’, mostly Soviet military personal who exposed themselves to radiation to clean up the site of the disaster.

Further work on the site was needed years later as the initial structure put over the reactor to contain it was collapsing due to the haste with which it was erected, and a new more modern metal shell was erected over the building in 2017.

It is heavily disputed how many deaths were caused by the disaster, with most estimates ranging from between 4 000 and 16 000. Most of these were caused by the long-term effects of radiation poisoning; 31 people died directly from the accident.

The accident highlighted the inefficiency, mismanagement and callousness of the Soviet system, as well as the unequal relationship between Russia and the other Soviet republics. The disaster was a massive blow to the prestige of the Soviet system, which was already in serious trouble at the time of the disaster, as the economy was faltering.

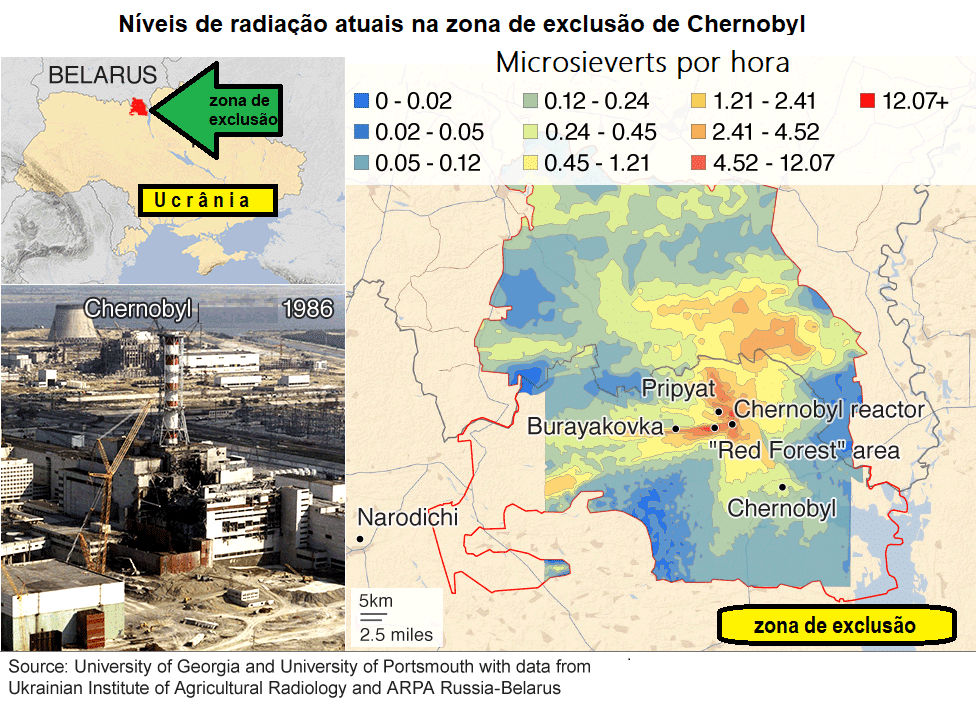

Today Chernobyl’s ‘zone of exclusion’ around the reactor has become a tourist destination, with hunting trips exploiting the flourishing wildlife, and tours through the abandoned city of Pripiyat, billed as ‘Eye-opening experience of post-apocalyptic world’ (https://www.chernobyl-tour.com/english/)

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend