This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

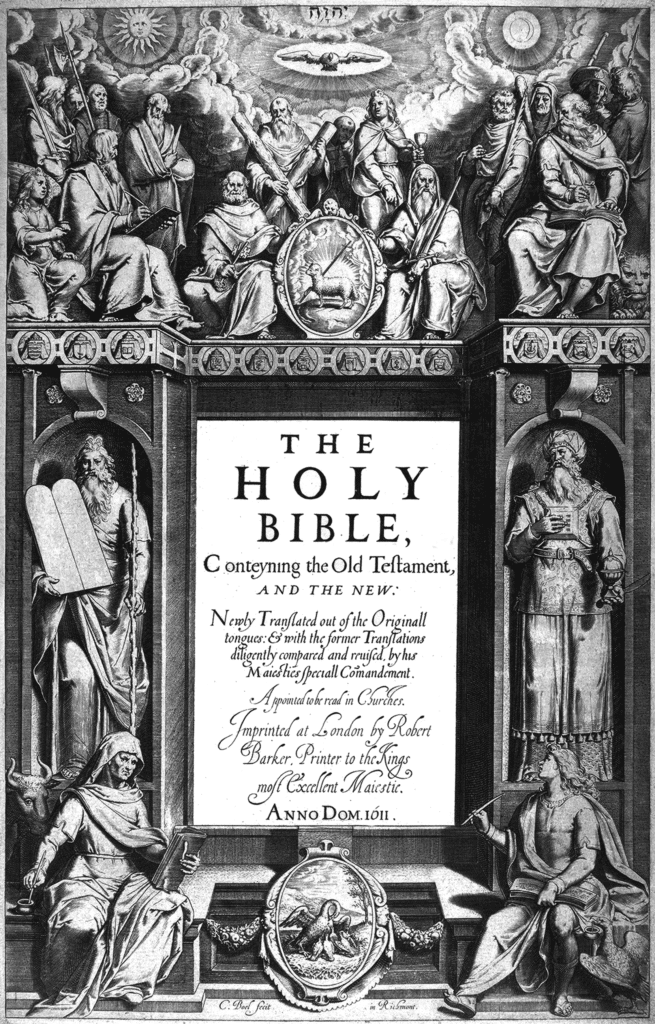

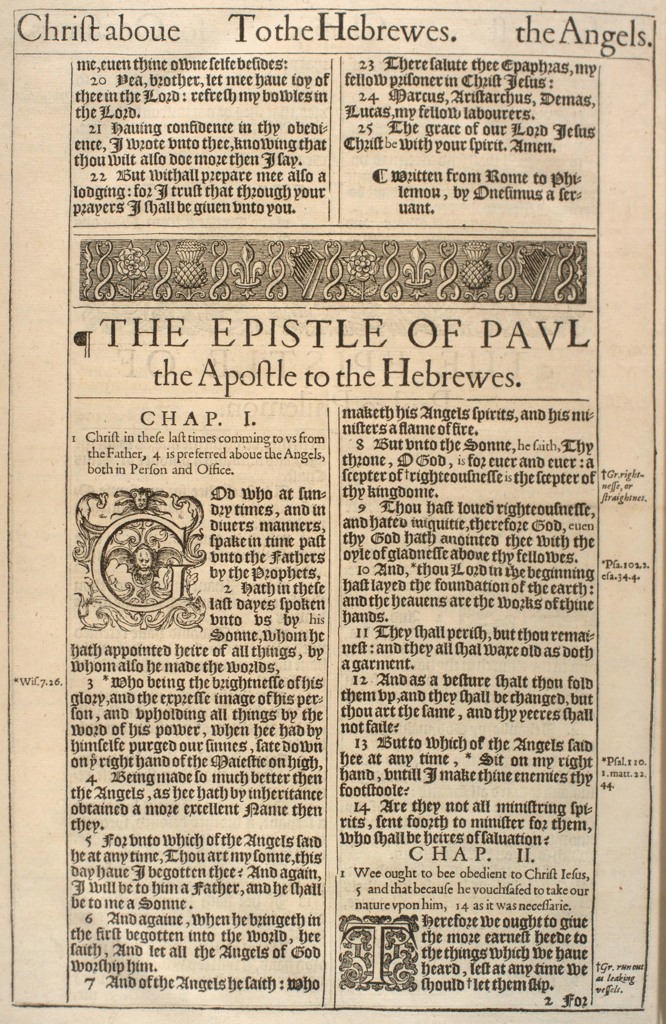

2nd of May 1611 – The King James Version of the Bible is published for the first time in London, England, by printer Robert Barker

After breaking from the Catholic Church, the Church of England and the English state authorised the printing of several versions of the Bible in English. The first was the so-called ‘Great Bible’ of 1535, during the reign of King Henry VIII. A revised version, called the ‘Bishop’s Bible’, was issued in 1568 during the reign of Queen Elizibeth I. However, by the end of her reign, the Puritans, a sect of the Anglican Church, raised several objections and concerns relating to the quality and accuracy of the translations included in the Bishop’s Bible and pushed for the Church to commission a new translation.

In January of 1604, the newly crowned king, James I, convened a meeting of the church, which decided to commission a new version in response to the Puritans’ concerns.

The king ordered the writers to ensure that the new version would conform to Anglican ecclesiology –and reflect the episcopal structure of the church. The leading Biblical scholars of the time – 47 in all – contributed to the project, translating the Bible from the original, Latin, Greek, Aramaic and Hebrew.

After several years of work, the new version, soon to be known as the King James Version, would be printed for the first time in London on 2 May, 1611.

This version would become the most widely printed book in history and would go on to have an enormous effect on the English language and the development of the English-speaking world.

3rd of May 1491 – Kongo monarch Nkuwu Nzinga is baptised by Portuguese missionaries, adopting the baptismal name of João I

The history of many of Africa’s kingdoms and empires from the pre-colonial period is generally not well known. Much of this is due to the lack of written sources, as even the African nations which did have writing often did not have comprehensive histories of their times that survive to the present day. Partly, this lack of knowledge is due to the difficulties of doing archaeological work in countries that are poor, have bad infrastructure and are dangerous to travel in. And, of course, modern academia’s obsessive focus on the history of colonialism and post-colonial politics also contributes to this problem.

It is for these reasons that the history of the Kingdom of Kongo is not well known outside of history obsessive circles. However, in contrast to many other African nations before the 1600s, we have far more knowledge about this kingdom due to its extensive contact with the Portuguese empire and the accounts written of the region as a result.

The Kingdom of Kongo was not the territory that forms the modern countries of the Democratic Republic of Congo or the Republic of Congo, but was centred on what is today northern Angola.

The Kingdom of Kongo was founded sometime around the year 1390, when the monarch of a small kingdom conquered his neighbours who lived on a mountain to the south. This king, who was named Lukeni lua Nimi, transferred his capital to the mountain, which was named Kongo, and the town there called Mbanza Kongo became the kingdom’s capital.

This city became one of the most densely populated areas in the region, a region which in many cases still remains sparsely populated to this day. The first Portuguese explorers who encountered the city of Mbanza Kongo at the end of the 15th century described it as a ‘large city’, probably with a population over 50 000, which was large by European standards of the time. This high population density allowed the kings of Kongo to centralize their realm and project power over the more scattered peoples who surrounded them.

By the time they made contact with the Portuguese, the Kingdom of Kongo was a major regional power, with an economy based on ivory, copperware, cloth, pottery and salves.

In 1483, a Portuguese explorer sailed into the territory controlled by the Kongolese and took some Kongo nobles back to Portugal to show them his homeland and establish links between the two nations. The nobles returned in 1485, and good relations blossomed between the two nations. Upon the return of the Portuguese, they were accompanied by Catholic missionaries and troops. The Portuguese managed to convince the Kongolese king that if he converted to Christianity, they would become powerful allies, and so on 3 May 1491, the King of the Kongo, Nkuwu Nzinga, was baptised and changed his name to João I, the same name as the king of Portugal at the time. Many of the senior nobles of Kongo also converted alongside their king.

João ruled for the next 18 years, during which time local Christian Kongo converts began writing and opening schools to spread Catholicism and writing to the Kongolese people. The king’s conversion didn’t last long, as Christianity’s requirement of monogamy threatened his power base, which was maintained by multiple marriages to the families of powerful nobles in his realm.

However, he continued to maintain friendly relations with the Portuguese, who supplied him with firearms. This weaponry helped to strengthen the kingdom against its neighbours and fend off raiders from the neighbouring Nsundi and Bateke kingdoms. These victories also allowed the Kongolese to acquire more slaves, which in turn could be traded for more firearms.

The Christianisation of the kingdom did not happen overnight, and when João died in 1509, the traditionalists sought to re-establish themselves as the dominant power. Two of the king’s sons, the elder son, Mvemba a Nzinga, also known as Afonso, and his brother, Mpanzu a Kitima, battled for the throne. Unlike in Portugal, succession was decided by a vote of the nobles rather than through hereditary succession. With the result disputed, the Christians and traditionalists gathered armies and faced each other at the Battle of Mbanza Kongo. The details of the battle are not well understood, but according to legend five saints appeared in the sky on horses and drove the traditionalist army before them.

Regardless of the truth of the matter, the Catholic army won the day and, after executing his brother, Afonso became the undisputed King of Kongo.

During Afonso’s reign, the trade in slaves increased as the Portuguese bought more and more slaves for use in their other colonies and Europe. Some Portuguese traders began violating the Kongolese laws on which people could be bought and sold as slaves, and Afonso wrote to the king of Portugal as well as the Pope complaining about the conduct of slave traders. These appeals failed and tensions grew between the two nations; the Portuguese even backed a plot to assassinate Afonso in 1540, though it failed.

The Kongolese and Portuguese remained allies on and off, sometimes fighting wars with each other and then rebuilding their alliance afterwards. The Kingdom of Kongo would continue to exist as an independent kingdom until 1857 when it became a vassal of the Portuguese crown. This lasted until 1914, when a revolt against Portuguese rule saw the kingdom abolished and its territory incorporated into the colony of Portuguese East Africa.

8th of May 2020 – First This Week in History

This week marks one year of This Week in History, which has been a delight to research and to write. I would like to thank all those who keep reading it week after week – your interest is greatly appreciated.

I hope to keep you interested and entertained for many weeks to come.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend