This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

10th May 1801 – First Barbary War: The Barbary pirates of Tripoli declare war on the United States of America

An often forgotten conflict outside of the United States, the First Barbary War was a defining moment for the fledgling American republic on the world stage, demonstrating that America was a power that could wield real influence outside the North American continent.

The North African states usually called the ‘Barbary States’ by Europeans consisted of the mostly independent Ottoman provinces of Algeris, Tunis and Tripoli, and the independent sultanate of Morocco.

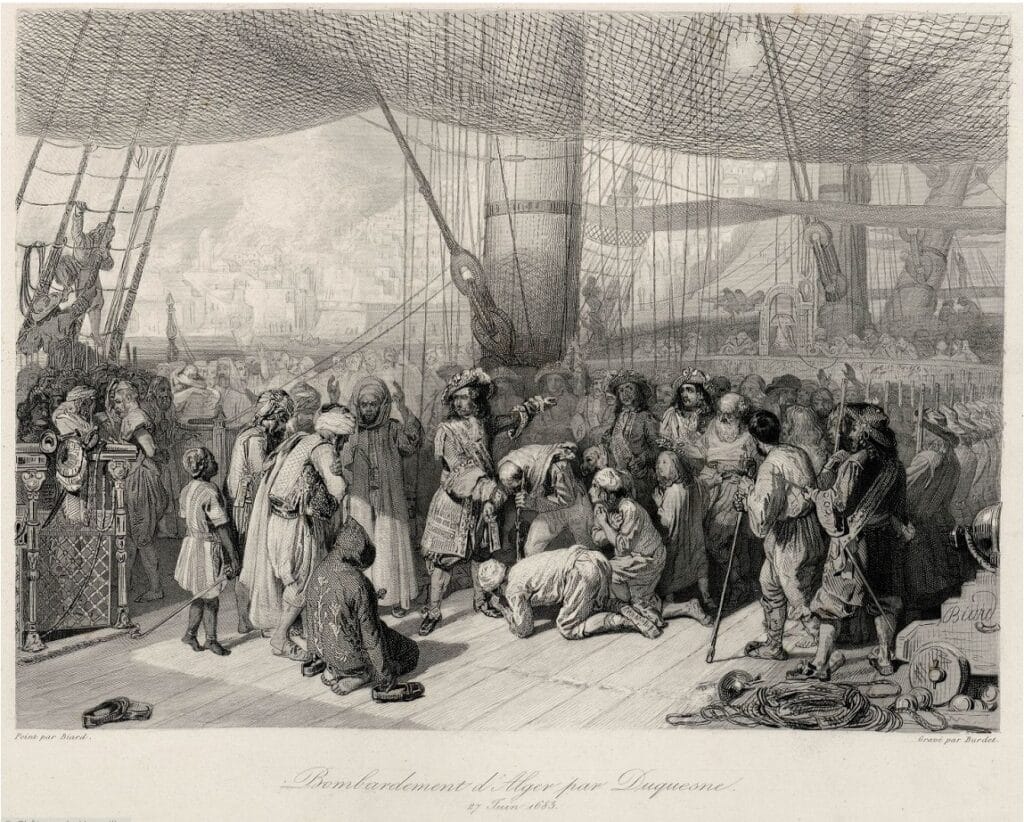

These nations were notorious for their slave raids and piracy; between the 15th and 18th centuries they carried out enormous numbers of slave raids and pirate attacks, mostly on Christian states in the Mediterranean, but even going as far as England and even once to Iceland. During this period, at least one million Europeans were captured, and enslaved for sale in the slave markets of the Islamic world.

When the United States entered the international stage during its war of independence, its shipping to Europe was under the protection of the French, as per the alliance they signed with France to help them win the war with Britain. Once the war ended, however, so too did the protection of the French, and the Barbary pirates saw an opportunity to begin targeting a new – weakly defended – source of income.

In 1784 Moroccan pirates seized an American ship and its crew and sent ransom demands to the American government, insisting the Americans pay regular tribute in return for safe passage for their merchant ships. The Spanish, who had been fighting and counter-raiding the Barbary States for centuries, helped the Americans by negotiating for the crew’s release, but advised the Americans that it would be much easier for them to simply pay the tribute to stop these attacks.

Under the direction of Thomas Jefferson, the American government dispatched a number of envoys to North Africa to discuss treaties they hoped would safeguard American shipping. The Moroccans signed an agreement in 1786 to end piracy against the Americans, promising to free any enslaved American citizens who entered their ports.

Envoys to the other states in the region were less successful, with each state demanding $660 000 (equivalent to millions of dollars today) from the United States. This was far beyond what the Americans were willing to spend. Further negotiations went nowhere, the ambassador from Tripoli telling the Americans, according to Jefferson: ‘It was written in their Koran, that all nations which had not acknowledged the Prophet were sinners, whom it was the right and duty of the faithful to plunder and enslave; and that every mussulman who was slain in this warfare was sure to go to paradise.’

Jefferson sent letters back to America arguing that any payment would encourage more attacks and that a more aggressive response was needed. Initially the American congress decided to pay ransoms instead, and in 1795 signed a treaty with Algiers, which included a payment of $642 500. The American government would also pay a yearly tribute of $21 600 indefinitely. This saw some prisoners released back to America.

The tribute demands were badly received in the US, however, and in 1798 the Americans founded the Department of the Navy to develop the capacity to resist the pirates’ demands. With Jefferson’s election as president in 1801, however, America definitively shifted to a more aggressive stance against the corsairs.

When, in that year, the lord of Tripoli demanded $225 000 from the Americans, Jefferson refused. In response, Tripoli declared war on the United States on 10 May 1801. Jefferson had already sent American warships to the Mediterranean but believed that he could not declare war without congressional approval, and so gave them orders to do what they could, short of war. When open war was declared, the American ships joined with Swedish warships in the area – as Sweden had been at war with Tripoli since 1800.

The southern Italian kingdom of Naples agreed to supply and support the American expedition from its ports in Sicily, and with Neapolitan help the American warships were ready for their first real test.

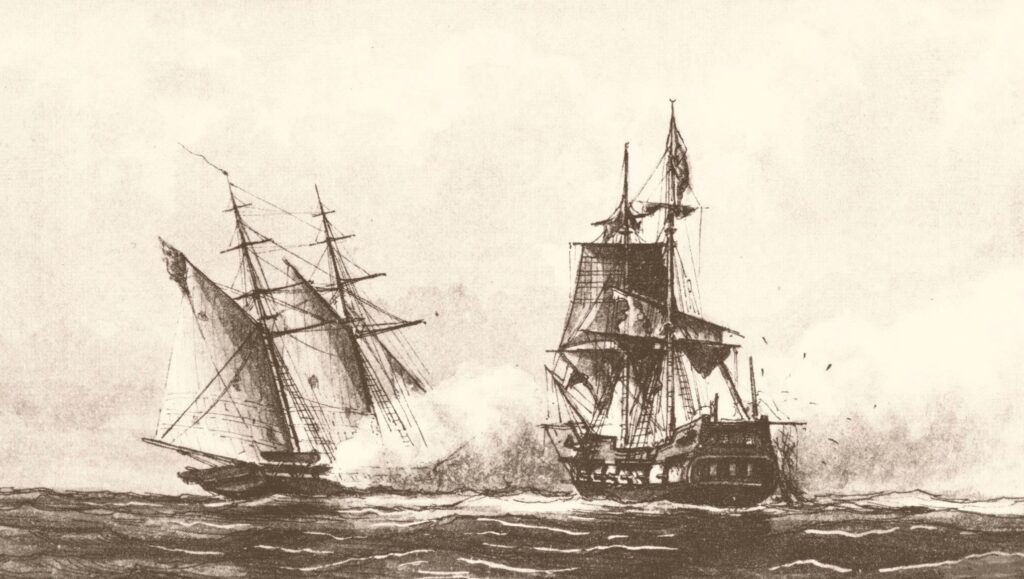

Fighting was uncommon, as the Corsairs couldn’t match the modern American ships. This was evident in a battle in August 1801 in which an American schooner smashed a Tripolitan warship in battle.

The Americans sought to blockade Tripoli’s ports and strangle their trade.

The blockade weakened Tripoli and numerous skirmishes were fought between ships of both sides, but the war did not end until an American force of Marines, warships and Greek and Arab mercenaries surprised the corsairs by invading Tripoli’s territory from Egypt and capturing the town of Derna in May 1805. This involved the American forces marching 839 km through the North African desert.

As a result, the lord of Tripoli agreed to ‘deliver up to the American squadron now off Tripoli, all the Americans in his possession; and all the subjects of the Bashaw of Tripoli now in the power of the United States of America shall be delivered up to him; and as the number of Americans in possession of the Bashaw of Tripoli amounts to three hundred persons, more or less; and the number of Tripolino subjects in the power of the Americans to about one hundred more or less; the Bashaw of Tripoli shall receive from the United States of America, the sum of sixty thousand dollars, as a payment for the difference between the prisoners herein mentioned.’

Jefferson said that payment for prisoners was ransom and not tribute and therefore completely different.

The Americans returned home, though the issue was not solved. Algeria soon resumed attacks on American shipping; distracted at the time by a war with Britain, the Americans would return to resolve the matter in 1815.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend