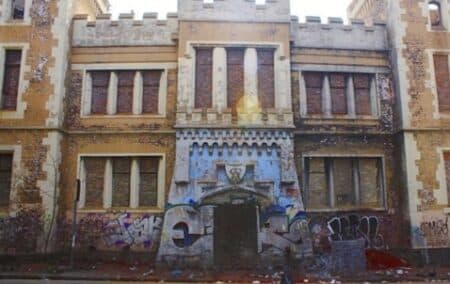

Stories about the decline of South Africa’s rural towns have been common for some time. But we are now seeing that even South Africa’s great cities are showing signs of what some would say is irreversible decay.

Some may sniff and say that complaining about uncut verges or lamenting the fact that it’s unsafe to go out and about in most South African cities’ central business districts (CBDs) is only a concern of the privileged, at a time when many South Africans find themselves living in shacks or in unsafe high-rise buildings.

The fact is that one can be concerned about more than one thing at the same time. Being concerned about people living in informal housing does not mean one cannot also be concerned about the continuing degradation of South Africa’s cities. And a city where most of the public spaces have fallen into disrepair is unlikely ever to be able to offer decent housing for everyone living there. It is also unlikely to be one with opportunities for people that are anything above a subsistence level.

The example of Lichtenburg in Disobotla municipality in North West, where the deterioration compelled Clover to close a factory in the town, shows how municipal decay has harmful economic and other knock-on effects.

And this is why South Africa’s urban areas need to be rescued as a matter of urgency.

Urban decay also often becomes a vicious cycle; as a town begins to collapse, it struggles to provide services (if these were ever a priority), and businesses and more affluent residents leave, meaning there is even less money for upkeep and services. And so on and so on.

Hubs of development

As happens around the world, South Africa’s cities are hubs of development, and attract people not only from other parts of South Africa, but from around the continent, and even further afield.

More than two thirds of South Africans today live in urban areas; the chart below shows how this phenomenon began to increase rapidly in the mid- to late-1980s, with growing numbers of black South Africans moving to the cities as apartheid began to collapse under the weight of its own contradictions.

And this is unsurprising. It is trite to say so, but there are more opportunities in South Africa’s cities, with their larger economies. South Africa’s eight metropolitan municipalities (Johannesburg, Tshwane, Ekurhuleni, Mangaung, Buffalo City, Nelson Mandela Bay, Cape Town, and eThekwini) account for just over 40% of South Africa’s population, but are responsible for close to 60% of the country’s output. If we add important secondary cities – such as, for example, Nelspruit, Rustenburg, and Stellenbosch – then the importance of urban areas as economic engines becomes even clearer.

Rates of unemployment are also generally lower in South Africa’s cities, sometimes significantly so. This is unsurprising, as cities provide more opportunities for people to access jobs.

Politically different

Politically, South Africa’s cities are also quite different from the country as a whole. If the 2019 election had been decided by how the vote went in our eight metros, then the governing African National Congress (ANC) would have missed out on a majority by a whisker. In 2019 the ANC managed just under 50% of the vote in the eight metros (compared to nearly 58% across South Africa as a whole). The Democratic Alliance (DA) would have won 30% of the vote (ten percentage points higher than its overall total) while the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) would have won 11.1%, slightly higher than its overall vote share. In three metros (Tshwane, Nelson Mandela Bay, and Cape Town) the ANC failed to win 50% of the vote.

This also has implications for South Africa. Cities are often bellwethers of national change, and South Africa is no different. The political path in the cities lights the way for the rest of South Africa – this country is soon to become one where no political party manages a majority.

Importance of governance

Be that as it may, it is vital that our cities are well governed. People will continue moving to the great cities of our country as they seek opportunities and a better life for themselves and their families.

Cities are the equivalent of vital organs in a body. If they begin to fail then the body that contains them will also start to fail. Someone with a defective heart or kidneys will be unhealthy and will need to take steps to become healthy. Of course, organ transplants are an option for a human being – but not for a city. The only option for a country is to make its cities healthier and the way to do that is through better policy.

South Africa’s cities must be places where businesses can thrive and where people want to live. This means making them safe, ensuring that services (such as water and electricity) are provided, and that there is affordable and decent housing close to employment and other opportunities.

At the same time, municipalities must see those who pay rates and taxes as partners, and not cows to be milked until they collapse. Ekurhuleni’s recent hike in property valuations (sometimes doubling the valuations), to enable the municipality to charge more in rates, is a case in point.

For South Africa to escape its current political and economic malaise, regeneration must start at the municipal level.

Our cities are dying. And if they die, so too will South Africa.

Municipal elections are scheduled for October. South Africans should use their votes wisely.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend