This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

August 5th 910 – The last major Danish army to raid England for nearly a century is defeated at the Battle of Tettenhall by the allied forces of Mercia and Wessex, led by King Edward the Elder and Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians

In 793, a monastery called Lindisfarne in northern England was sacked by Viking raiders. This raid set off a wave of incursions against the British Isles by Vikings from Denmark and Norway, which caused mayhem and devastation.

The raids culminated in the arrival of the ‘Great Heathen Army’ in the British Isles in 867, when the Vikings ceased returning home for the winter and switched from raiding to conquest.

Over the next few years the Great Heathen Army smashed its way through the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England, conquering Northumbria, East Anglia, half of Mercia and nearly destroying the Kingdom of Wessex. With a combination of skill, cunning and luck, the Anglo-Saxon king of Wessex, Alfred the Great, managed to save his kingdom from the Vikings.

Alfred slowly pushed the Vikings back, converting some to Christianity, establishing the first English navy to fight the Vikings on the water and building a series of forts across the English countryside to protect the inhabitants from Viking raids and deny Viking armies supplies.

When Alfred died in the year 899, he had begun to call himself King of the Anglo-Saxons, in effect becoming the first King of England.

The Vikings had been forced back into north-eastern England, a region which became known as the ‘Danelaw’ due to many Vikings from Denmark settling in the area and establishing their laws over it.

When Alfred died, he was replaced by his son, Edward, who soon took up his father’s work of fighting to drive the Vikings out of England.

During the first decade of the 900s, Edward fought the Vikings occupying East Anglia, and raided Danelaw territory.

In retaliation, the Vikings of the Danelaw organised a large raiding fleet and sailed up the River Severn, plundering and looting as they went.

When they attempted to retreat back to their territory, the Anglo-Saxon army of Edward and his ally Æthelred, met the Vikings near the town of Tettenhall.

Here they fought a massive battle in which the Viking army was crushed, most of their troops killed or captured and many of their leaders killed.

It was a decisive moment in the power balance between Saxons and Vikings, and from this point on the Vikings of the Danelaw would never again pose a significant threat to the English Kings, who would soon bring them back under Anglo-Saxon rule.

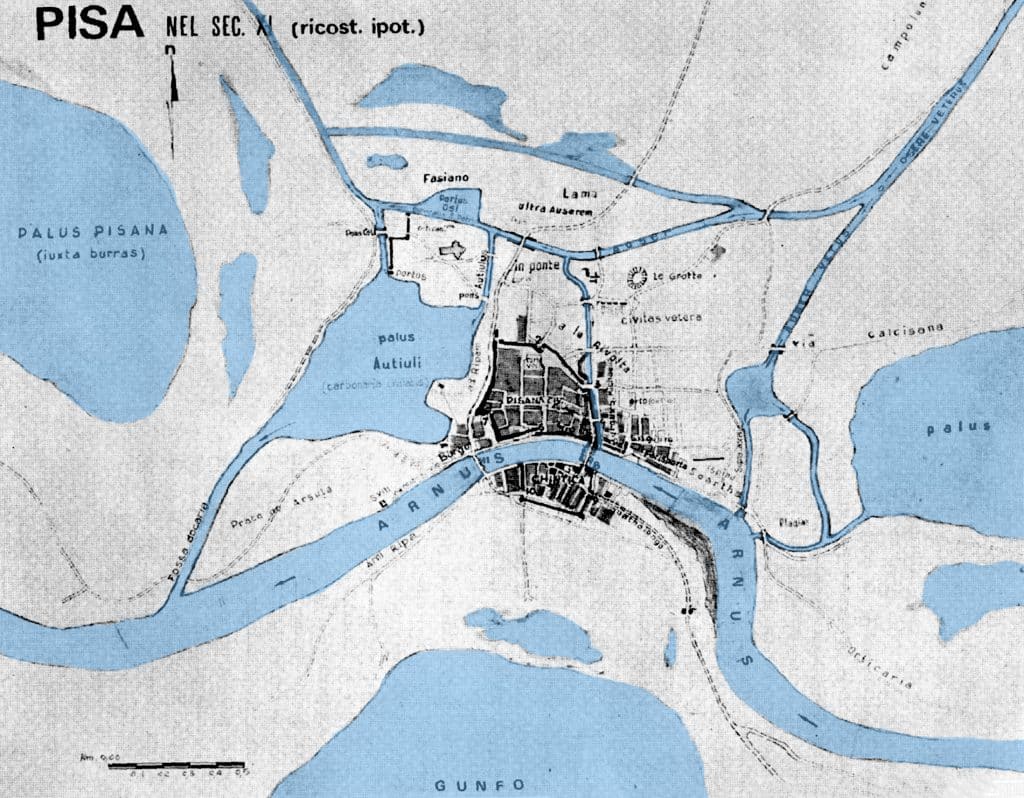

August 6th 1284 – The Republic of Pisa is defeated in the Battle of Meloria by the Republic of Genoa, thus losing its naval dominance in the Mediterranean

For much of the Middle Ages, the north of the Italian peninsular was made up of a group of squabbling city states which battled endlessly against foreign invasions and among one another. As one of the only places in Medieval Europe with a major urban population, the cities of northern Italy were centres of trade, innovation and thought, driven in part by their wealth but also by the fierce competition between them.

Starting in the 1000s the wealthy merchant republic city states of Pisa, Genoa and Venice began to expand their trade networks around the Mediterranean and Black Seas, seeking to control the flow of spices and other goods from the Islamic world into Europe.

During the 1200s the merchant republics began to establish colonies as far away as Crimea, where the Genoese took control of a number of cities on the Crimean and Black Sea coasts.

During the late 1200s, Genoese and Pisan merchants competed aggressively for control of the trade coming out of the Eastern Roman Empire and from the Black Sea, and this competition soon led to war between the two cities.

In 1282 the Genoese struck first by blockading the River Arno in northern Italy so as to interrupt Pisan commerce. During 1283 the Pisans and Genoese prepared for a major confrontation and began building up their naval forces.

In 1284, the Pisan fleet of 72 galleys and possibly around 20 000 crew rowed out to face a Genoese fleet of around 88 galleys and perhaps 22 000 crew. The Pisan force was the vast majority of the city’s power, and the fleet was crewed by most of the city’s nobility and armed men.

In the clash that followed, known as the Battle of Meloria, the Pisan fleet was decisively smashed by the larger Genoese force and a huge number of its sailors and soldiers killed or taken prisoner. Shortly after Pisa was attacked by its neighbours in Lucca and Florence, who greatly weakened it.

Following the disaster at Meloria, Pisa was crippled and faded away until it was finally conquered in 1406 by Florence, which took its place as the dominant city of Tuscany.

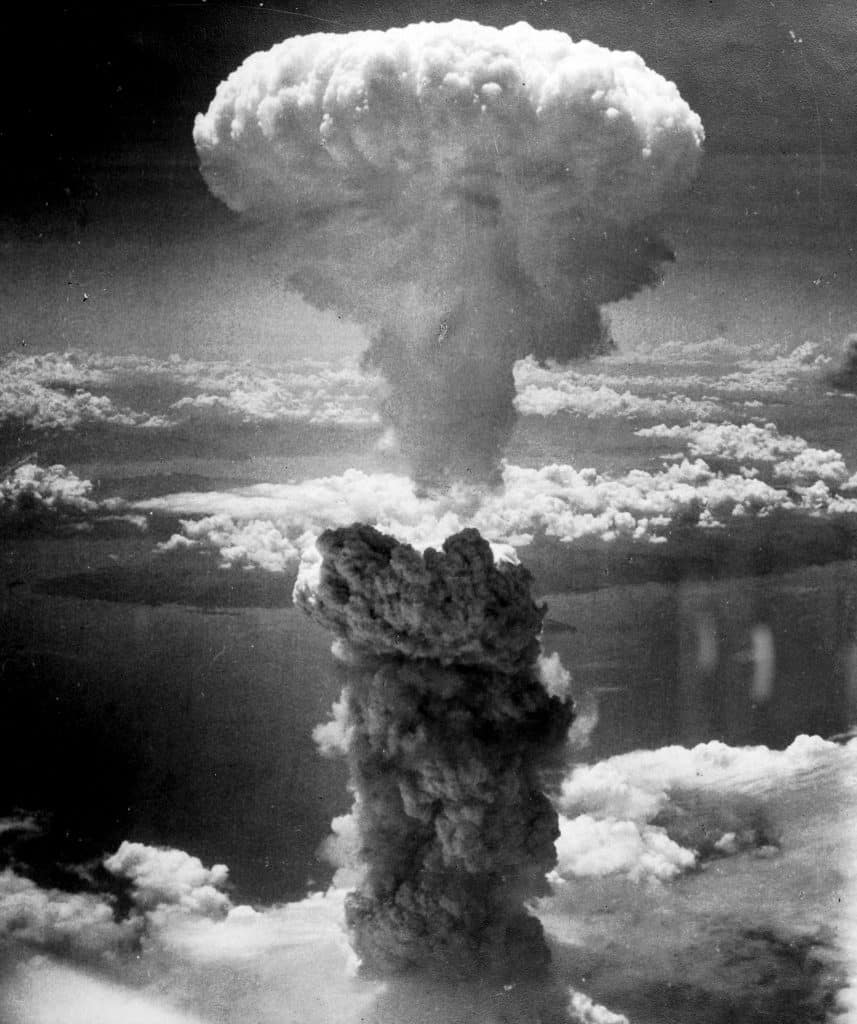

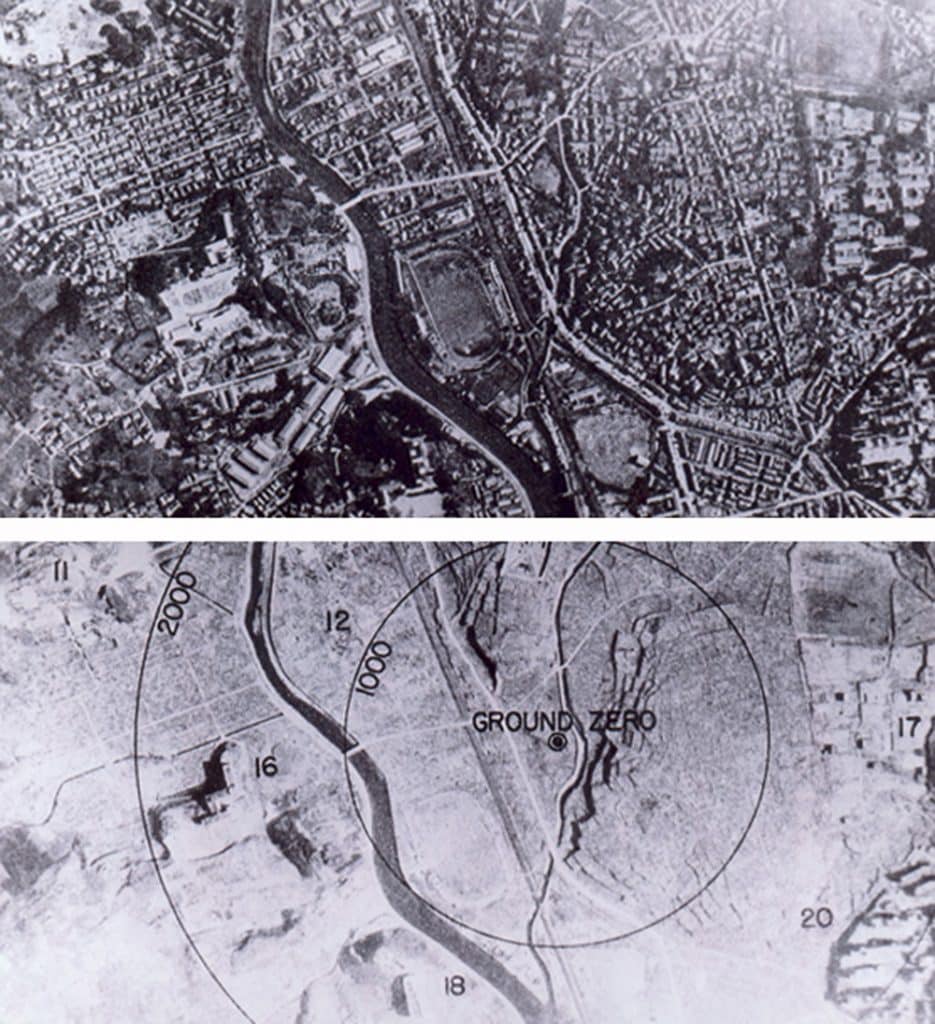

August 9th 1945 – World War II: Nagasaki is devastated when an atomic bomb, Fat Man, is dropped by the United States B-29, Bockscar. Thirty-five thousand people are killed outright, including between 23 200 to 28 200 Japanese war workers, 2 000 Korean forced workers, and 150 Japanese soldiers

On 9 August the American air force dropped the second atomic bomb on Japan, the last atomic weapon used in war.

The destruction of the city and the declaration of war by the Soviet Union on Japan finally tipped the balance of forces in the Japanese government and resulted in the surrender of the Japan end of the Second World War.

For more on this topic and the planned, but never executed, American invasion of Japan, check out this two-hour interview with American historian and author, D M Giangreco:

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend