This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

29th August 708 – Copper coins are minted in Japan for the first time (Traditional Japanese date: August 10, 708)

Coinage and formal currency are a technology that often took a surprisingly long time to develop in many parts of the world. The great civilisations of the Bronze Age in Egypt, Greece and Turkey, for example, did not use coins. This would change at the dawn of the Iron Age, and the technology would spread over the world in the coming centuries.

In Japan, the first coins found in the country were Chinese coins. However Japan at the time had a very unsophisticated economy and as such these were more like precious items rather than currency. Instead, prior to the 700s, the Japanese traded using arrowheads, rice grains and gold powder, items which in themselves held value.

During the 600s, Japan was increasingly influenced by China, and the rulers and elites of Japan sought to copy almost everything they could from China, including writing styles, dress, religion, government and soon money. Some Japanese nobles and merchants probably began to use or mint their own coins during the later 600s, though there was no official currency.

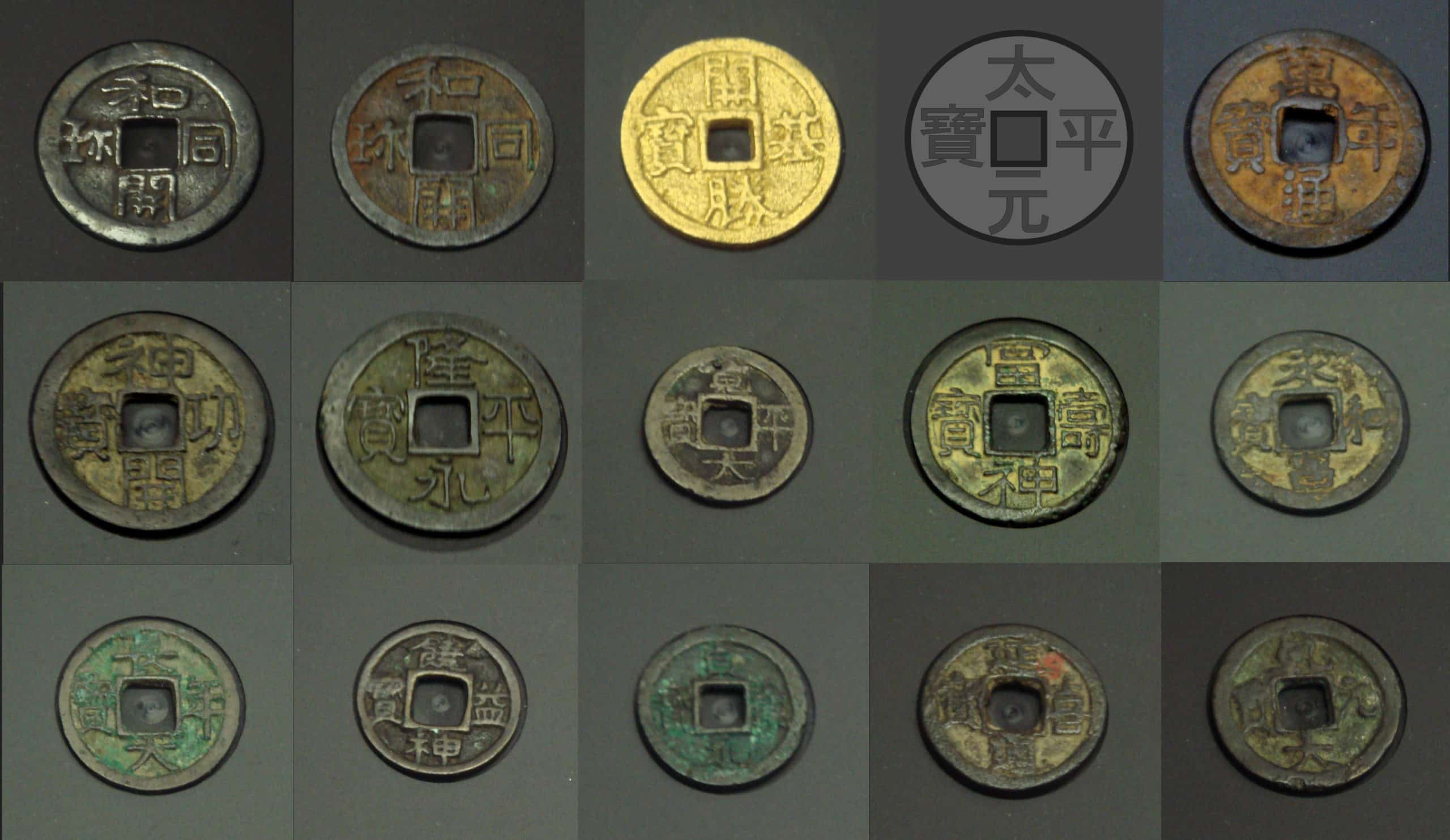

This would change when under the orders of the Japanese Empress Genmei, on 29 August 708, the Japanese government began to mint the first official currency, coins called Wadōkaichin, which were made of copper and, like the Chinese coins of the period, had a hole in the middle so that they could be strung together.

This first coin would remain in circulation until 760, when the value of the coin had plummeted due to constant debasement of the copper content and rampant counterfeiting. This would see the Japanese government reform the currency, introducing silver and gold coins.

1st September 1449 – Tumu Crisis: The Mongols capture the Emperor of China

In 1368, a rebellion against the Mongol-dominated Yuan dynasty managed to drive the Mongols out of China and return rule of China to a dynasty from the Han Chinese population. This new dynasty, called the Ming Dynasty or the Great Ming, would see China reach a high point in development and prosperity, before its decisions to close China off from the world would begin a relative decline, with the Ming falling to invading Manchu warriors in 1644 after a series of revolts and natural disasters.

The Mongol Yuan dynasty did not simply surrender and die when they were driven from China, and while they were greatly diminished in power and wealth, they did still call themselves heirs of Genghis Khan’s empire. This Mongol state is usually referred to as the Northern Yuan Dynasty. And while it still held on to the legacy of its founder, in reality the Khans of this new state were puppets of the Oirat Mongol clans of western Mongolia. The northern Yuan rump state, despite its pretensions to glory, was often riven with internal conflict and domination by the Ming.

Beginning in 1438, a new Oirat warlord called Esen Taishi rose to power in the Northern Yuan territories and crushed many of his enemies on the Mongolian steppe before turning his attention towards Ming China. Taishi tried to extort gifts from the Ming, and while at first the Ming tried to buy him off, they would later reverse course and close the border to trade, instead seeking to support his rivals and undermine his authority over the Mongols. This was something Taishi couldn’t tolerate.

Under the banner of his puppet Khan Toqtaq-Buqa, Taishi launched a major invasion of Ming China in 1449 at the head of an army of 20 000 troops which in all likelihood was more a raid than a conquest, perhaps seeking to scare the Ming into reopening the border.

The invasion achieved some quick successes.

The most powerful person in the Ming court at the time was a eunuch named Wang Zhen, who encouraged the 22-year-old emperor that the best way to show his ability as a ruler was to lead the Ming armies personally and face the Mongol invaders head on. The Ming quickly threw together a huge army of 500 000 troops and a staff of 20 experienced generals to accompany the emperor and Zhen, and marched north to drive the Mongols back, and hopefully march into the steppe and punish the Mongols for their invasion.

Upon reaching the frontier, Zhen was advised that it was too dangerous to chase the Mongols into the steppe as they might be cut off without supply. So, after recapturing a fortress that had fallen to the Mongols, the huge army declared victory and began to march home. They chose a fairly exposed route to return to the capital, as Zhen feared that the army marching past some estates he owned on the safer route home would damage them. On 30 August 1449, Mongol troops attacked the rearguard of the huge Ming army, routed it and drove on towards the heart of the army.

The next day, the court officials demanded Zhen send the emperor ahead to a nearby walled city, but fearing this would look bad, Zhen refused.

On 1 September 1449, the Mongol army, despite being vastly outnumbered surrounded the huge disorganised and panicked Ming forces. Taishi told the Ming to negotiate surrender, a request which Zhen refused. Zhen then tried to march the army out of the trap and in the battled that followed the Ming army was almost entirely wiped out. All the Ming generals were killed, including Wang Zhen, and the Emperor was captured.

The massive disaster left the Ming shaken and the Mongols shocked at the scale of their victory. Taishi tried to ransom the emperor back to the Chinese and negotiate a favourable trade treaty, but the Ming general left in command of the capital refused to negotiate.

After years of unsuccessful ransom demands, the Mongols released the Chinese emperor without ransom, and for this humiliation, Taishi would be assassinated by generals a few years later.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend