For many of South Africa’s political class – its politicians, its activists, and its commentators – the ‘platteland’ is less a part of the country’s geography than its imagination. It is a space in which events can be interpreted with particular ideological contexts and motives in mind. From this, narratives emerge which are close to the heart of those driving them, but simultaneously at a remove from their day-to-day lives. They may also not accord with the realities of the world as it exists in those parts…

This is all too often the case where violence is involved, and especially when it crosses racial boundaries: it feeds politically satisfying narratives that may owe more to the observers’ preconceptions than to a sober assessment of the events themselves. Yet it should not be necessary to make the point that real lives, and real imperatives of justice are at stake.

Two weeks ago, Qiniso Dlamini, a seventeen-year-old resident of Sithembile township in Glencoe in KwaZulu-Natal and student at Sebenzakusakhanya High School, died after being shot on the farm of Garth Simpson, a 68-year-old farmer whose property adjoins the township.

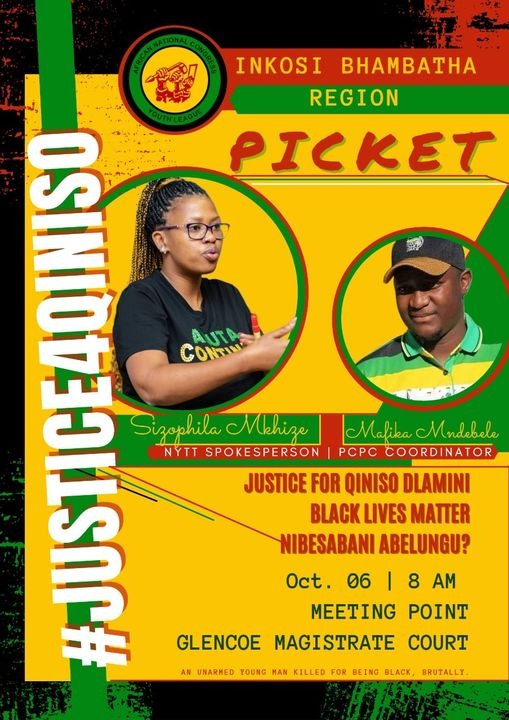

Lest anyone miss the inevitable narrative, Sizophila Mkhize, a senior member of the African National Congress National Youth Task Team, tweeted a few days later: ‘A 17 Year old [sic] Qiniso Dlamini was brutally murdered by a white farmer in KwaZulu Natal eNdumeni Tuesday evening. The farmer accused the boy of allowing the cows to eat “his grass”.’

Do not mistake the severity of this: a young man is dead.

Cases like this stir passions. When Simpson appeared in court two days after the incident, on 30 September, an angry crowd greeted him. A few carried incendiary posters – bearing such comments as ‘Kill the Boer, Kill the Farmer’ – and demanded that he be held in custody. There was an attempt by protestors to breach the court, presumably to mete out punishment themselves.

Concerned about these developments, the Institute of Race Relations sent a team to investigate the situation, to understand its background, and to attend the bail hearing on 6October.

Background

Of all the pressures to which farmers in South Africa – established or emergent, commercial or subsistence – are subjected, the security and stewardship of their livestock must rank as one of the most acute. A study published by Agri SA in 2018 found that a staggering 70% of commercial farmers reported having been victims of crime just in the previous year, which climbed to well over 90% in KwaZulu-Natal. Of those who experienced crime, 40% reported suffering from stock theft. According to Willie Clack, chairperson of the National Stock Theft Prevention Forum, as well as a penologist and a farmer, the monetary cost of this crime is around R1.4 billion annually. For individual farming operations, it can push them to bankruptcy.

Along with this, livestock farming depends on safeguarding of the health and sustenance of herds. For an outsider, these are not obvious concerns, but to a farmer they are the stuff of survival. Grazing land – or even more basically, the grass on which animals feed – is an economic resource without which livestock farming cannot take place. And as with any valuable resource, it is a scarce one. The world over, herders come into conflict with one another over their claims on it: it is not uncommon for these conflicts to turn deadly.

The movement and grazing of livestock, meanwhile, raises the question of biosecurity. (This is something that should be apparent to laypeople in the age of Covid-19.) A disease outbreak can have immediate and costly ramifications for livestock economy, at the level of an individual farm, a region, or a country as a whole. The 2019 Foot-and-Mouth outbreak – which seized up production in a number of provinces, occasioned a nationwide ban on livestock auctions and led to some of our neighbours prohibiting the import of South African livestock – is a salutary reminder of what is at stake. Not for nothing did Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform, and Rural Development Thoko Didiza comment that this had ‘a devastating effect on the economy of the country as a whole’. President Cyril Ramaphosa memorably retrenched a number of his farming staff at this time.

For these reasons, enormous resources are invested in keeping herds safe, both from theft and disease. The security of farm boundaries or the intermingling of animals from different herds are not mere inconveniences; they can amount to a very real threat to the viability of a farming operation.

For subsistence farmers, livestock is a valuable resource which is often up against the limits of what a given holding (or an unclearly delineated landholding) can support. The tensions that this is primed for are obvious.

These concerns are widespread across South Africa and were raised by representatives of the farmers’ association we spoke to. Indeed, it seems that livestock roaming about was something of a local talking point. One resident shared a humorous WhatsApp message showing a cow drinking from a pothole outside Dundee, a photograph which had apparently been taken recently.

On the telling of the farmers’ representatives, attempts to deal with stock theft and to secure the perimeters of farms have been an uphill battle. Fences are often vandalised, and it is said, the authorities decline to take seriously the theft of animals, unauthorised grazing, or the movement of others’ herds over their land. Herman de Wet of local the farmers’ association commented that Simpson had been hard hit by this and had tried for years secure his boundaries and to lay charges against alleged transgressors, to no avail.

So, what took place?

Garth Simpson, looking dishevelled in a faded purple tracksuit top, was ushered into the courtroom in the late morning of 6 October.

There were no jeers, no scornful shouts from those in the gallery, most of whom were evidently there to see the Glencoe farmer denied bail. There was something vaguely discordant about the scene: among the attendees, sat people in the regalia of the ANC, DA, IFP, and EFF, alongside one another. The details of what transpired on that fateful day will be interrogated in court. Nevertheless, the presentations made in the course of the bail hearing give a sense of the narratives unfolding.

The basic details on which both the defence and prosecution agree are that on 28 September, Simpson impounded some 34 cows in a kraal near his house. In the course of the afternoon, a group of young men arrived at the kraal to claim their cattle. Words were exchanged, and Simpson retrieved a firearm – a 12-gauge shotgun – from his house. Returning to the kraal, the situation escalated, and a shot was fired which resulted in the death of Qiniso Dlamini.

Simpson faces a charge of premeditated murder. In addition, on the day of the bail hearing, a number of other charges were added, relating to the unlawful possession of firearms and ammunition.

The defence counsel’s account was that Simpson impounded the cows that were grazing illegally on his property. He noticed that a number of them bore the brand of a former neighbour who had suffered theft some time previously. He then phoned the local stock theft unit, but they apparently did not arrive before things turned violent.

Shortly thereafter, two men came to the kraal to retrieve the cattle, claiming to identify five of the cows. At this point, there did not seem to be anything to indicate the violent turn things would take. This changed when an additional four young men arrived, including Dlamini.

On this version, Dlamini stated that they had come to burn Simpson’s farm and kill him. Based on the threat, Simpson felt that his life was in danger, and he went to his house to fetch a gun.

When Simpson returned with the firearm, he approached the men who were in the process of releasing the cattle. At this time, Simpson instructed his son, Dean, to begin video recording the events. Simpson fired a warning shot and was then assaulted by four of the men, including Dlamini. During the assault, the assailants attempted to seize his firearm. At this point, the firearm was accidentally discharged, the blast hitting and killing Dlamini. The defence, therefore, argues that the deceased was the catalyst and author of his own misfortune.

Despite this, Simpson immediately called both the police and an ambulance. More appropriate than charges, the defence maintains, would be an inquest.

The prosecution, meanwhile, has not yet completed its presentation, but has thus far relied heavily on the testimony of the investigating officer in the case – it is his version that essentially constitutes the second narrative.

On this account, the cattle were impounded while being driven by the herdsman. The latter, along with some associates, subsequently arrived to ask for them to be returned. They pleaded with Simpson to release the cattle as some amongst them belonged to elderly members of the community (note here that cattle are frequently a major repository of value). Two more men arrived, including the deceased, who had been summoned as some of the cows belonged to them. Simpson’s response was that he would release the cattle for R20 a head. The men declined and continued to plead for the release of the cattle. Simpson refused and the men tried to release the cattle.

Simpson said that he was going to fetch a firearm, walking a distance of around one hundred metres to his house to do so.

When he returned so armed, Simpson adopted an intimidating posture, pointing the firearm at each of the men saying that he would shoot them. The men were angered by the threats. Simpson then singled out Dlamini and approached him in a threatening manner, in so doing initiating the physical altercation.

Dlamini, who was now afraid for his life, began to kick and strike Simpson in self-defence. Three others joined the altercation trying to intervene by separating Dlamini and Simpson. Dlamini was then shot. The prosecution says that Dlamini was one metre away from the muzzle of the firearm when it was discharged, arguing that the discharge was not accidental.

Thoughts from a court… and beyond

Perhaps it was the inherent stoicism of a courtroom and grief over the tragic loss of a community member that had the gallery sitting quietly waiting for insights into the truth of what happened on 28 September. Perhaps the lapse of time had calmed – outwardly at least – the emotions.

Outside, however, the police were not taking any chances. Reinforcements had been called in from the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, and barriers thrown up to ensure that demonstrators were kept at bay. There was a measured professionalism in this. ‘Why are we here?’ a policewomen from out of town asked us, genuinely curious about her deployment.

Prior to the hearing, we had spoken to a number of people who had come to support the Dlamini family or to demand that bail be denied or for whatever reason to understand these events better. One supporter, wearing ANC regalia, told us that she had known Dlamini since he was a child and spoke highly of him. A member of the family – who introduced himself to us as Sibonelo Khulu – was strident in demanding that bail be denied. It would, he said, be an ‘insult’ if it wasn’t. He seemed firmly convinced of Simpson’s guilt and intentions. Interestingly, in contrast to much of the political rhetoric, he denied that this was about race. Rather, he was focussed on the charge and expressed frustration about the impounding of cattle.

There has been another aspect of this, though. We heard repeated reports of threats of violence against Simpson and members of his family. His property has been attacked by arsonists.

The ANC Youth League had put out a message calling for a demonstration with the exhortation: ‘Nibesabani abelungu?’ – ’What are you afraid of from white people?’ (To underscore its message, literally, the foot of the notice carried the words: ‘An unarmed young man killed for being black, brutally.’)

During the midday break in the court proceedings, we spoke to protestors who echoed some very disturbing sentiments, threatening violence against Simpson, to ‘hunt him down’ in one formulation.

How widespread this may be is unclear. But it was noteworthy that the defence put in a provision in its application for bail that Simpson may need to relocate owing to threats of violence, and the prosecution based part of its argument on danger to public order that would ensue if bail should be granted. Blood would be ‘splattered’ and the situation would be ‘uncontrollable’, the investigating officer said to the prosecutor.

For Simpson’s supporters, this has been compounded by concerns around the investigation. It seems that the initial investigating officer, having viewed the video footage, indicated that there would be no objection to bail. When he was replaced, it seems that not only was this position reversed, but knowledge of the footage denied. Moreover, Simpson was reportedly taken directly from hospital, where he was undergoing treatment, to Ladysmith prison, where it is unclear whether he is receiving the medical care he needs.

The video footage itself is the subject of contention. It is probably the strongest piece of evidence in Simpson’s favour and looks set to feature strongly in the defence’s case. Why, after all, would Simpson have asked for the confrontation to be filmed if he had criminal intent in mind? The prosecution, unsurprisingly, has sought to minimise its impact, asking it to be discounted for bail considerations. The need to authenticate the footage and the possibility of manipulation was raised in court (including by the presiding magistrate) and will probably feature in the trial.

Also of apparent importance, particularly to the prosecution, is that Simpson purposefully fetched a gun. There was considerable debate as to the distance he traversed to do so – was it the 100 meters propounded by the prospection, or a more modest 30 to 35 as per the defence? This seems to be intended to speak to whether there was a calculated intention to kill.

Aligned to this is the complicating fact that the shotgun used was not licenced, or more accurately, its licence had lapsed and not been renewed. Hence the charges – introduced on the morning of the 6th – of being in illegal possession of arms and ammunition. (A number of other firearms were in Simpson’s possession, which had similarly expired licences.) A great deal of emphasis was placed on this by the prosecution. So was the fact that he had used a shotgun rather than a handgun, whose purpose is self-protection. The implication appears to be that he chose a more powerful weapon to do more harm – although we find this idea implausible, since both can be lethal, and a handgun’s design is such that it is to be used to incapacitate and kill humans; shotguns are in fact often used for public order policing.

However, this sits alongside the actions of Dlamini himself. Why did he not only strike and kick but move through a fence to accost Simpson? If he was concerned for his safety, it seems rather counterintuitive, especially after the warning shot had been fired. From a layman’s perspective at least, this would seem to make evasion all but impossible, and physical injury rather more likely.

Finally, we were struck by the questions made towards the end of the prosecution’s presentation, and the investigating officer’s response. Would we be here, the prosecutor asked, if certain ‘government departments’ had performed their duties properly? He clarified by this that he meant the Department of Rural Development or people in charge of land issues. Speaking through a translator, the officer replied: ‘Yes, I do confirm we would not be where we find ourselves.’

Whether this helps or hinders the prosecution’s case, and whether the investigating officer is well positioned to make this judgement is unclear. But it is significant that this matches precisely with the frustrations that we have seen over and over again, across the country, and in this corner of it, from voices across South Africa’s diverse spectrum. Hermann de Wet suggested that it was necessary for various stakeholders – farmers, religious and traditional leaders, community representatives – to come together to try to chart a way forward. This is sage advice. These are issues that require cooperation, not polarisation.

Indeed, the more we looked into this, the bigger the story became. Questions of immediate culpability are crucial. No less is the need for justice for all, in accord with the facts, not a political agenda. Indeed, political agendas are frequently the enemies of justice. Simpson’s fate must hinge on a sober reading of the law and the facts. But the facts at hand open up a wider circle of considerations. This is about grazing and boundaries, security and governance. Everything points towards a complex of circumstances that have been allowed to grow to the point of a fatal event.

The bail hearing continues today.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend