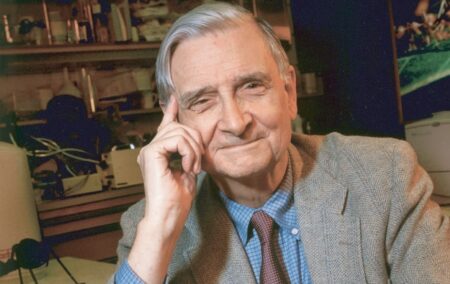

Celebrated American naturalist Edward Osborne Wilson, hailed in his lifetime as ‘the modern-day Darwin’, in part for his controversial views on human behaviour, died on Boxing Day.

Wilson dedicated his life to understanding and preserving the natural world. He was a giant in his field of entomology (the study of insects) and was affectionately nicknamed ‘the ant man’.

He was born on 10 June 1929, in Birmingham, Alabama. His parents divorced when he was young and he lived a nomadic lifestyle with his alcoholic father. He spent most of his time outdoors and came to view nature as his most enduring companion.

A childhood fishing accident left him partially blind in one eye. As a result, Wilson focused on the ‘little things’ that his 20/10 vision would allow for, particularly the comings and goings of ants.

It has been said of him that while he may have studied little things, he drew far-reaching and profound conclusions that changed the thinking on topics as big as human nature, the conflict between science and religion, and our role in preserving biodiversity.

Wilson was awarded a PhD from Harvard in 1955 and was part of the faculty from 1956 until his retirement in 1996.

He wrote over 30 books, two of which (On Human Nature and The Ants) won Pulitzer Prizes. In 2008, he was elected one of the 100 most important scientists in history by the Britannica Guide and was included in Time magazine’s 1995 list of the top 25 most influential Americans.

Wilson’s work was not without controversy. In 1975, he published Sociobiology: The New Synthesis – in which he used evolutionary principles to explain the behaviour of social insects and using those principles, sought to understand human behaviour.

At the time of publication, the idea of the tabula rasa (blank slate) informed the dominant view of human behaviour. That is to say that nurture, not nature, was responsible for how humans behaved. Wilson found that this contradicted what he had observed in other social animal behaviour and proposed that genetics was the leash that controlled our individual and social behaviour.

For his views on human nature, Wilson was accused of racism, sexism and flirting with eugenics. His ideas led a group of his colleagues to write an open letter criticising him for his ‘deterministic view of human society and human action’.

Despite fierce criticism of his views, Wilson continued to be led by his empiricism and time has largely vindicated his early research.

Wilson was acknowledged an influential science communicator with the ability to elegantly turn a phrase.

He once said that destroying a rainforest for economic gain was like burning a Renaissance painting to cook a meal; he thought that Karl Marx was right, socialism did indeed work, just not for the human species; and that the real problem of humanity was that people had palaeolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and god-like technology.

He once observed: ‘Still, if history and science have taught us anything, it is that passion and desire are not the same as truth.’

Peers said Wilson would be greatly missed by the scientific community, and remembered for his rigorous research, intellectual non-conformity, and contribution to raising public awareness of the necessity of environmental preservation.

[Image: Jim Harrison, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4146822]