This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

20th December 1948 – Operation Kraai: The Dutch military captures Yogyakarta, the temporary capital of the newly formed Republic of Indonesia.

The Dutch had ruled the region known as the ‘Spice Islands’ for centuries, establishing themselves in 1602 after pushing out the Portuguese, who had previously dominated the islands. Over the next few centuries the Dutch came to dominate the archipelago, conquering or absorbing the remaining local kingdoms.

The Indonesian archipelago is made up of several larger Islands – Java, where most of the people live; Sumatra, the long island in the west; Borneo, the large northern island, which is mostly jungle; and New Guinea in the east – and thousands of smaller islands, including Bali, Lombok, Tidore and Ternate. The administrators of the Dutch East Indies came to control all of these islands, except the northern section of Borneo, the eastern section of New Guinea, and half of the island of Timor, which remained a Portuguese colony.

These vast holdings meant that by the 20th century, the Dutch controlled a massive empire, much larger and more populous than their homeland on the other side of the world. Discriminatory practices and a rising Indonesian middle class, who demanded more say in their governance, led to the formation of an Indonesian independence movement at the start of the 20th century. This movement was originally focused more on working with the Dutch, within their institutional frameworks to slowly attain more independence and peacefully transition away from colonial rule.

Everything changed, however, with the outbreak of the Second World War.

The Dutch, their homeland having been occupied by the Germans, and with their allies engaged in a fight for survival, had no real way to defend their empire against the Japanese empire. On 10 January 1942, following their surprise attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbour, the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies and in short order defeated the Dutch, American, British and Australian forces.

While the Japanese occupiers treated the local Indonesians extremely poorly – an old Indonesian man once remarked to my father, ‘The Japanese were more cruel in three years, than the Dutch were in 300’ –their official propaganda encouraged Indonesian nationalism and claimed that Japan was protecting their fellow Asians from European colonialism as part of a greater East Asian ‘Co-Prosperity sphere’.

The Indonesian nationalists took this opportunity to solidify their control of the country and break from the Netherlands. As the war turned against the Japanese, the Japanese offered ever more rhetorical support to the Indonesians, promising them independence if they continued to fight on their side. However, when Japan was defeated, the Indonesian nationalists feared that all their gains would be reversed.

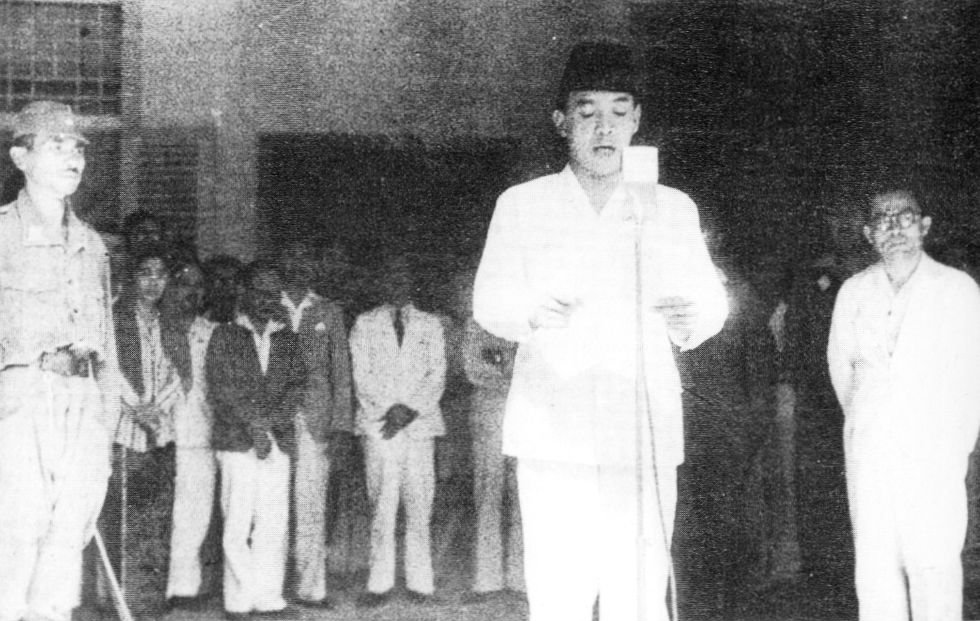

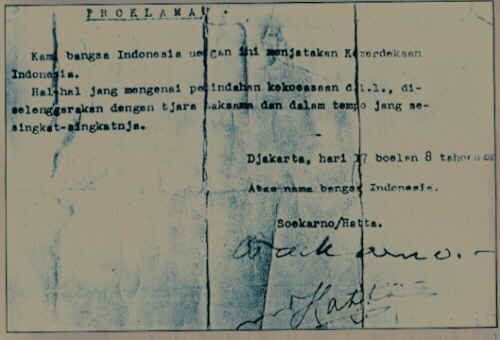

Thus, under pressure from radical elements within their coalition, the leaders of the nationalists declared Indonesia an independent republic a few days after Japan’s surrender in August 1945.

Most of Indonesia was still occupied by Japanese troops, who had been given orders to lay down their arms and keep the peace. To accomplish this goal, many of the Japanese turned over their weapons to Indonesian militias and in effect helped to create an Indonesian army.

After a delay caused by an Australian strike, British and Australian troops arrived in Indonesia to try and restore order. Dutch troops would follow in the coming years, delayed by the Dutch government’s having to reorganise itself in the aftermath of the Second World War. Due to their weak position, the Dutch first opted for negotiations with the Indonesians. An agreement with Indonesia was signed in November 1946 recognising de-facto Indonesian control of some areas of the archipelago, but the Indonesians soon broke the agreement and so fighting resumed. By 1948 the Dutch had pushed the Indonesian republicans out of most of the big cities and into the countryside.

In January 1948, the Dutch and Indonesians agreed to another ceasefire, and negotiations continued. The Dutch wanted to turn Indonesia into a highly decentralised federal state, while the Indonesians wanted a more centralized state dominated by Java.

Differences among the republicans, and a stalemate in negotiations, led the Dutch to believe that if they broke the ceasefire with a powerful offensive, they could defeat the Indonesians decisively. Having decoded the republicans’ radio codes, the Dutch were now also aware of all of their plans and unit placements.

On 20 December 1948 the Dutch launched Operation Kraai, an attack on the republican capital at Yogyakarta. The surprise attack by the better-trained and -equipped Dutch quickly smashed the republican troops and the Indonesian government was forced to flee into exile. Within days, the Dutch had secured all of their objectives and declared victory. Guerrilla fighting by the Indonesians continued, however.

While militarily successful, the operation was a PR disaster for the Dutch, particularly in the United States, which was outraged at the violation of the ceasefire. The American government soon threatened to pull all Second World War reconstruction aid to the Dutch government if they did not resolve the conflict soon. In January 1949 the United Nations passed a resolution condemning the Dutch government and ordering an immediate end to the conflict.

On 7 May 1949 the Dutch and Indonesian republic signed a treaty called the Roem–Van Roijen Agreement. This saw the Dutch agree to withdraw from Indonesia, and provided for a federal Indonesia along the lines which the Dutch had hoped for. All captured Indonesian leaders would be released by the Dutch and the war would end. The United States of Indonesia would be created on 27 December 1949.

The federal structure of the country would last only a year and would be dissolved in 1950 with the declaration of a unitary Republic of Indonesia. This led to an Indonesia dominated by the island of Java. Indonesia has since been plagued by separatist movements across many of its islands.

25th December 1000 – The foundation of the Kingdom of Hungary: Hungary is established as a Christian kingdom by Stephen I of Hungary

You can read about the pagan past of the Hungarian people in the early Middle Ages in this earlier edition of This week in history.

Following their defeat by the Germans in the 950s, the Hungarians were greatly weakened and were unable to conduct the raids across Europe for which they were notorious. They were also adopting more and more of the habits of their neighbours, settling down and favouring farming over the old herding lifestyle of their ancestors. At this time the Hungarians were ruled by a grand prince who was elected by the various tribes which made up the Hungarian confederation. The power of these princes was fairly weak, and history does not record many of their reigns. The Hungarians at this time had also begun to adopt the Christianity of their neighbours, with some being baptised by the Greek Byzantines and others by the Latin Catholics. Many of the Hungarians remained Pagan, worshipping the ancient god of the open sky as their ancestors had done.

Sometime around the 970s, a son was born to a Hungarian chief called Vajk. Much of Vajk’s early life is in dispute, as the medieval sources offer conflicting, or vague, details about his religion, birthplace and parents, which are disputed by historians. He was likely born to a Christian family and, once baptized, was known by the Christian name Stephen. What is known is that the grand prince of the Hungarians, Géza, had Stephen elected as his successor around the time Stephen was 14 or 15, and that he was later married to the German Duke of Bavaria’s daughter, Gisela.

Grand Prince Géza died in 997 and Stephen was elected Grand Prince of the Hungarians by a meeting of the tribes. In reality, Stephen only controlled a small area of Hungary, as the chiefs of the various tribes acted more or less independently. Stephen’s claim to rule was challenged by his older relative at the time, Koppány, who claimed his right to rule by seniority. He represented the more pagan factions in Hungary, while Stephen drew support from the more Christian-aligned Hungarians.

Stephen and Koppány soon came to blows; in a decisive battle, Koppány was killed and Stephen remained as the unchallenged Grand Prince of the Hungarians. Stephen now had ambitions to be more than a Grand Prince; he sought to be king of all Hungarians. Soon Stephen began exercising control over all of the chiefs of the Hungarian tribes, and decided to strengthen his legitimacy further by seeking the aid of the Pope in Rome.

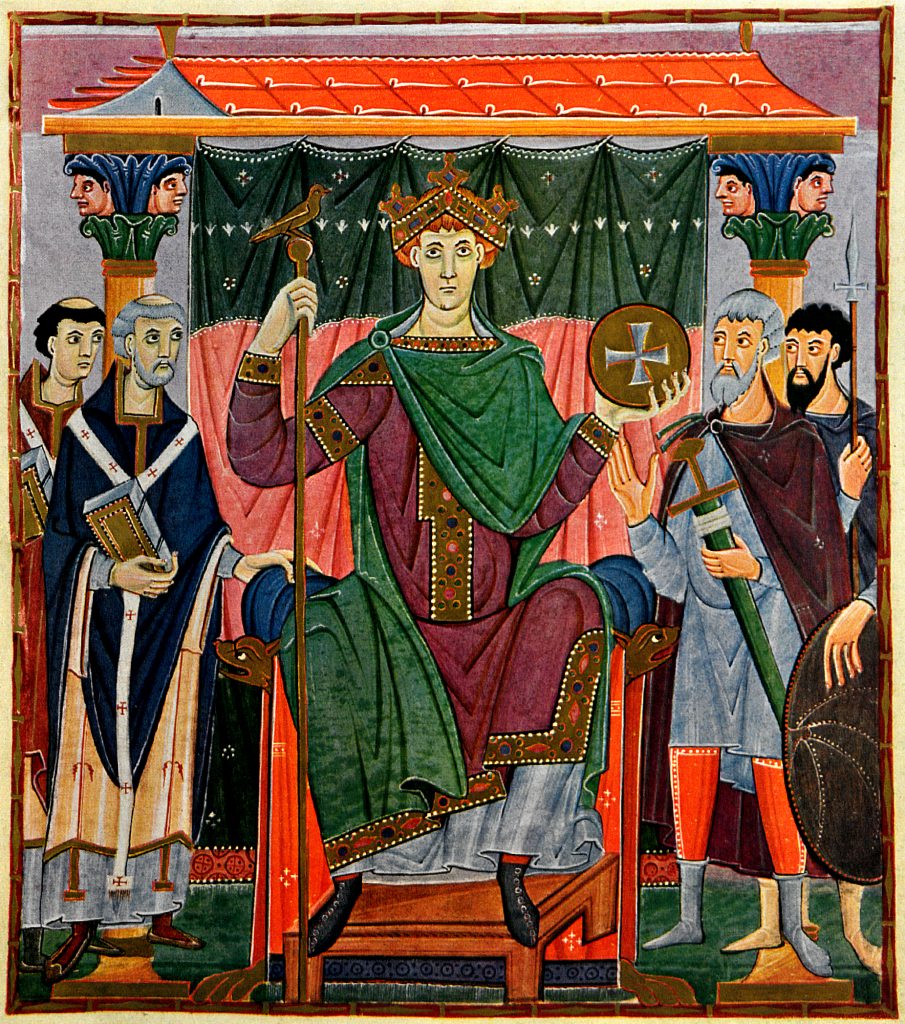

With support from the German emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Otto III – who hoped that the Christian king in Hungary would protect his south-eastern flank – Stephen approached the Pope and asked to be crowned King of Hungary. This request was supported by the Pope.

While the date is disputed, tradition holds that on 25 December – Christmas Day – in the year 1000, Stephen was crowned King Stephen I of the Hungarians. He soon after established an archbishopric in Hungary and began the process of converting the Hungarian tribes into a modern Christian kingdom.

Making extensive use of the clergy, Stephen consolidated his rule over the tribes of Hungary. He fought many battles against his more unruly subjects, and some of his neighbours, managing to win many victories. When Stephen finally died in 1038, he had transformed Hungary into a centralised Christian kingdom, which would last until 1919.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend