This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

10 February 1355 – St Scholastica Day riot

From the modern vantage point, it can be difficult for us to properly grasp how differently states used to work in the medieval world. ‘De-centralised’ is underselling it; when you passed from the lands of one lord to another, even within the same kingdom, in some cases you might as well have been passing from one nation to another. Even more so when you crossed the threshold of a church, much of medieval Europe being governed by ecclesiastical law rather than secular law. Of course, don’t forget towns, which often had no local feudal lord and instead owed allegiance directly to their king or duke. As a result, towns often had a great degree of autonomy and their citizens tended to be freer than the peasants of the countryside.

People also usually identified themselves far more with their local power than with a nation or a language group. The people of a town such as York or Hamburg would see themselves first and foremost as citizens of that town and only distantly did they consider themselves the subjects of a king or emperor.

This extreme decentralisation often fostered close bonds of community with the people who lived around you. But it wasn’t all upside; indeed, the decentralisation of identity and political power also led to almost constant conflict between lords, towns, bishops, kings … and universities. While sometimes this conflict was legal, fought out in royal courts, often it was extremely violent and extrajudicial.

This brings us to the town of Oxford.

An Anglo-Saxon settlement founded at a ford for oxen in the 10th century, the town first grew as a military outpost between the kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia. The town continued to grow in importance through the decades despite several sackings by the Danes and Normans. In 1191 it gained a royal charter, granting it extensive rights and privileges similar to those of London.

Historians are not sure when the famous University of Oxford was founded but some believe it to be close to the end of the 11th century. What is known is that the university was massively boosted when the English king banned English students from studying in Paris in 1167, forcing them to seek education in England. The university was granted a royal charter, establishing it as a separate official entity in 1248.

Even before its charter was granted, the communities of the University of Oxford and the town of Oxford often had a tense relationship. The people of the town resented the foreign students who came from all over the British isles and were unfamiliar with local customs and often (as university students do) caused trouble. These resentments often boiled over into violence, a notable example of which was in 1209 when the townsfolk lynched two scholars from the university who were blamed for the death of a local woman.

These occasional lynchings periodically caused students and scholars to leave and form new universities (such as Cambridge). These acts of violence continued for decades and fighting between the townsfolk and students was common.

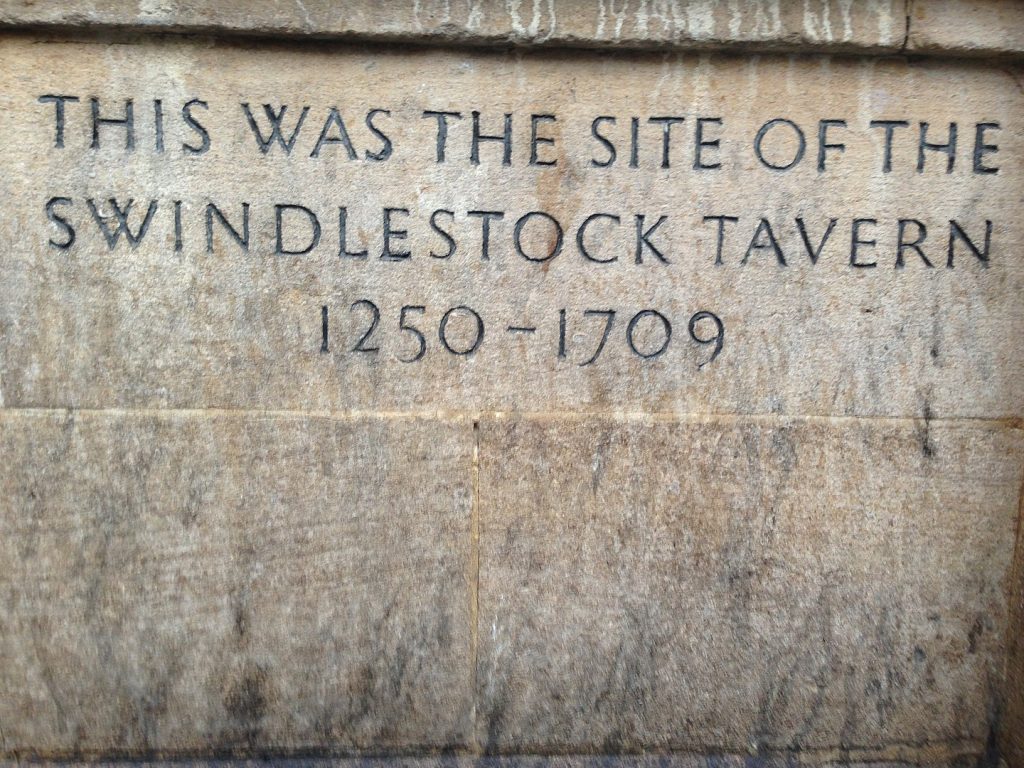

On 10 February 1355, several students went for a drink at a local tavern, the Swindlestock Tavern in the centre of Oxford (Oxford at the time likely only had a population of 5 000-6 000 and so was very small).

The students ordered some wine, which when it arrived, was not to their liking. They demanded a better drink and an argument between the owner of the establishment and the students ensued. Several ‘snappish words passed’ and then were met with ‘stubborn and saucy language’. Drinks were thrown in faces, and a fight began.

Quickly townsfolk and students joined the fight and it spilled out into the streets. Within 30 minutes the townsfolk and the students were ringing the bells of their respective churches summoning reinforcements to join the fight. Soon both sides were armed with clubs as well as bows and arrows. By nightfall on the first day there were no serious injuries or deaths and the setting sun put a halt to the fighting.

The chief magistrate of the town and the chancellor of the university tried to calm the two sides and issued orders they hoped would stop the fighting. The town bailiffs however decided to arm themselves and when the sun rose the next day, a group of about 80 armed townsfolk began to hunt down and kill students from the university. With that, fighting began again.

Unfortunately for the students, the townsfolk had hired peasants from the countryside to join them in the fight and in the late afternoon of 11 February, 2 000 peasants arrived seeking to massacre the students. The students barricaded themselves in wherever they could, but many were killed by the rampaging mob.

The king happened to be nearby and was appealed to for aid; he quickly dispatched a proclamation ordering the townsfolk to cease the attacks and not kill any students. This had no effect and the riot continued for a third day.

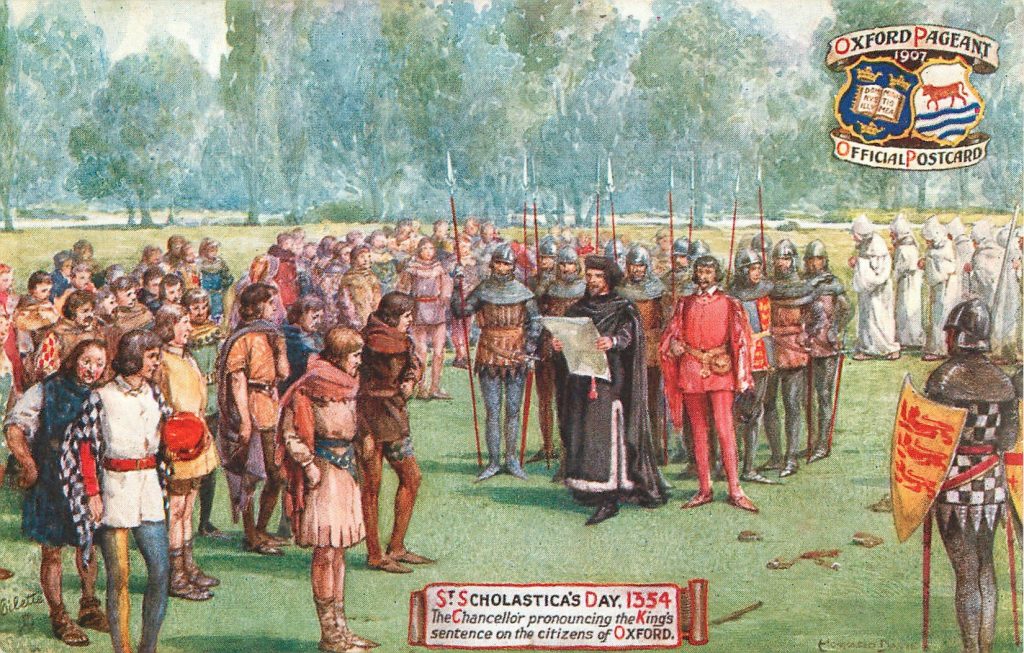

At last royal judges arrived and managed to put a stop to the killing. All in all, around 93 people had been killed, 30 from the town and 63 from the university. The king fined the town, and arrested the mayor and bailiffs. A commission of inquiry was organized, and the church banned the town from almost all religious activities for a year.

Soon after, charters were issued by the king which made the university superior to the town and the town’s sheriff’s henceforth had to swear an oath to not only protect Oxford, but also uphold the rights of the university.

Violence would continue between the town and students, but it was never on the scale of the 1355 riot.

The townsfolk continued to do penance in church for the riot until 1825, when it was finally dropped. In 1955 in a ceremony of reconciliation the mayor was given an honorary degree and the vice-chancellor was made an honorary freeman of the city of Oxford.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend