This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

1st April 1572 – In the Eighty Years’ War, the Watergeuzen capture Brielle from the Seventeen Provinces, gaining the first foothold on land for what would become the Dutch Republic

In the early- to mid-1500s the Hapsburg Empire, centred in Spain and Austria, was one of the largest the world had ever seen, being truly global in its nature. Previous empires, like that of the Mongols, had been larger, but the Hapsburg’s empire held territory in Europe, North and South America, Africa and Asia. This great empire was defended by the world’s most powerful navy and funded by trade and the huge silver and gold mines of the Americas.

This empire was all united under a single King, Charles V (1519-1556), whose list of titles would fill several pages.

Unlike other empires in history, the Hapsburg Empire of Charles V was far more a collection of feudal titles, tributary agreements and colonial conquests than one coherent administration. In Europe Charles was King of Spain, and Archduke of Austria, and Holy Roman Emperor and Duke of Burgundy, along with many other smaller titles. These lands had little in common, and no unified administration; they simply shared a ruler. As such, Charles worked hard to balance many competing factions and his attention was always split between his many lands, ensuring that all of his nobles were kept happy.

This was a great burden on a ruler, and as Charles V neared the end of his life, he began to abdicate his various thrones, passing them on to his various relatives and splitting up his mighty empire into an Austrian half, which continued to hold the title of Holy Roman Emperor, and a Spanish half which held all of Iberia, southern Italy and the former lands of the Duchy of Burgundy, which were situated in the Low Countries, modern Netherlands and Belgium and eastern France.

On 16 January 1556, Charles’ son Phillip II inherited the Spanish part of his father’s empire.

Charles had been born in Flanders in the Low Countries and so he was intimately familiar with the complex nature and customs of his lands there. Phillip on the other hand was a child of Spain, enmeshed in Spanish culture and focused on the Spanish parts of his empire (and the kingdom of his wife, Mary of England). As such, Phillip appointed Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, as his governor over the Low Countries, and took little interest in this region initially. Despite being in the Low Countries at the time of his accession to the Spanish throne, he did not govern the area himself and left after three years, never to return.

Phillip also differed from his father in that he was far more hard-line a Catholic. By the 1560s, the Protestant movement had been gaining ground for several decades across Europe and while Charles had battled with the Protestants, he had ultimately decided to grudgingly tolerate them, signing the Peace of Augsburg with Protestant princes in Germany allowing the Protestants some degree of religious freedom. Phillip by contrast was far keener to stamp out the heretics and instituted policies across his empire which sought to hunt down Protestants and execute them, regardless of what the local laws on heresy said.

Phillip’s lack of familiarity with the Low Countries, and his religious intolerance caused much resentment among the nobles and commoners of the Low Countries, especially among the Protestants. A Dutch noble called William of Orange who served in the Spanish government in the Low Countries, emerged as one of the most influential figures in among the discontented of the Low Countries. Initially William tried to seek concessions from local Spanish authorities and worked to lessen the prosecution of heretics. Phillip however dragged his feet and made little in the way of real concessions.

Eventually a petition was sent to Phillip demanding the end of the persecution of Protestants. The local Spanish government agreed, but Phillip overruled them and rejected the petition. Rebellion broke out in 1566 and Phillip dispatched the Duke of Alba to crush the rebellion. Initially this was successful and most of the rebels were forced to flee the country.

The rebels however demonstrated their skill at naval combat early on and continued to fight the Spanish, mostly from the sea while in exile. These rebels were initially called ‘naught but beggars’ by an advisor to the Spanish Regent of the Low Countries; they adopted this title as a badge of honour and began to call themselves the ‘Watergeuzen’ or Sea Beggars. Initially they based themselves in England, but in 1572 were expelled by the English.

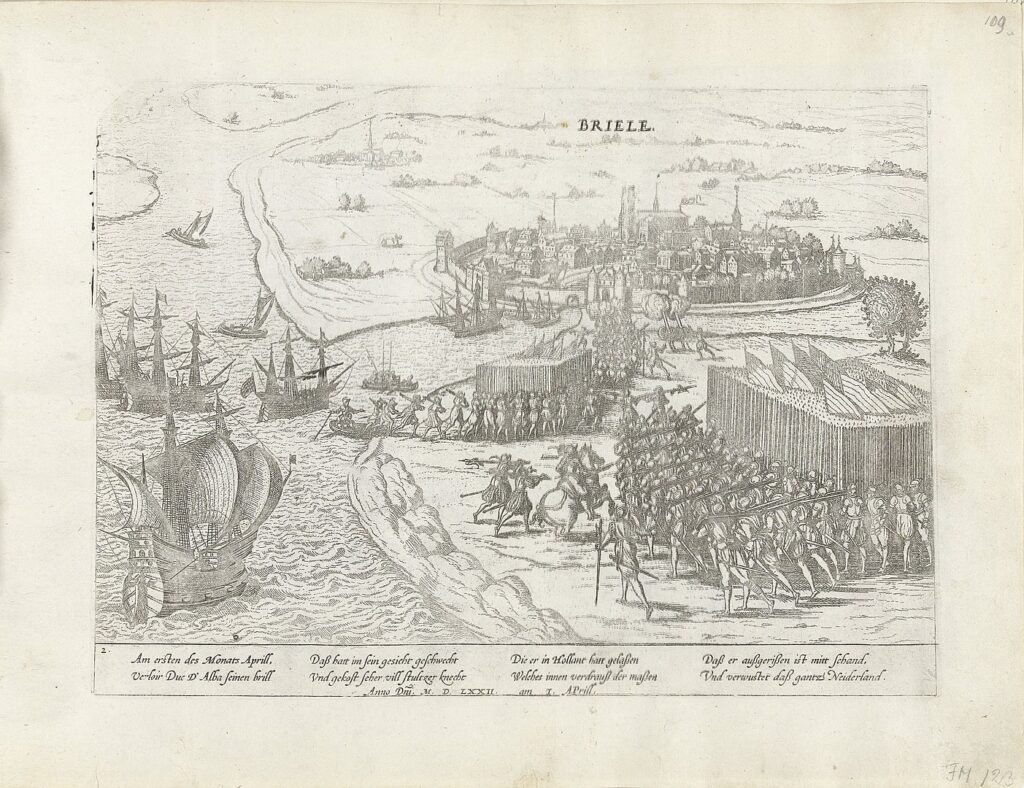

Seeking a new base of operations, the Sea Beggars sailed to the Port town of Brielle which had been left undefended by the Spanish, as they were to the south of the town fending off a potential French invasion.

On 1 April 1572 they captured the town and so breathed new life into the rebellion which was by this point close to being crushed.

From here the Sea Beggars captured more and more towns in the swampy lands of the northern Low Countries, towns which were almost impossible to capture without control of the sea, which the Spanish were unable to do as their naval forces were stretched thin across their vast empire and the Dutch were exceptionally skilled sailors.

The revolt against Spanish rule would come to be known as the Eighty Years’ War, a drawn out and grim struggle which ended in the recognition of the Netherlands as independent and saw the newly formed Dutch state carry the war to the colonial empires of Spain and Portugal (part of the Spanish Empire at the time).

The war against the Spanish and Portuguese colonies saw the establishment of Dutch colonies in the Far East.

Travel to these colonies would be made much easier by the establishment of a refreshment station on the southern tip of Africa. Such a station would be established on 6 April 1652 by the Dutch East India Company commander Jan van Riebeeck.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend