The failure to get South Africa onto a trajectory of rising, sustained and shared prosperity is the seminal tragedy of the country’s post-apartheid history.

No issue is as important for the country’s future, since for many South Africans, the legitimacy of democracy is coupled with an expectation of material improvement. As the July riots last year demonstrated, deprivation can be manipulated by opportunistic and unscrupulous politics. Although South Africa has begun to recover from the damage of the Covid-19 pandemic, even official Treasury estimates for future performance hold that it is unlikely to significantly exceed its past sup-optimal performance.

Among the initiatives to turn this around was the National Planning Commission, and the National Development Plan (NDP) it produced. Greeted with great fanfare when it was released in 2012, it envisaged South Africa to have put itself on a new economic and developmental path within two decades, with its governance and economic problems if not solved, at least progressively alleviated.

However, a 2020 review of the NDP’s performance made for disappointing reading. At one point, it commented: ‘Countries with significantly lower per capita incomes, like Indonesia or Vietnam, had poverty rates in 1994 that were far higher than South Africa, but by 2014 they were either similar or significantly lower. Lessons must be drawn from them to understand how they made such significant progress in improving the quality of life for their people.’

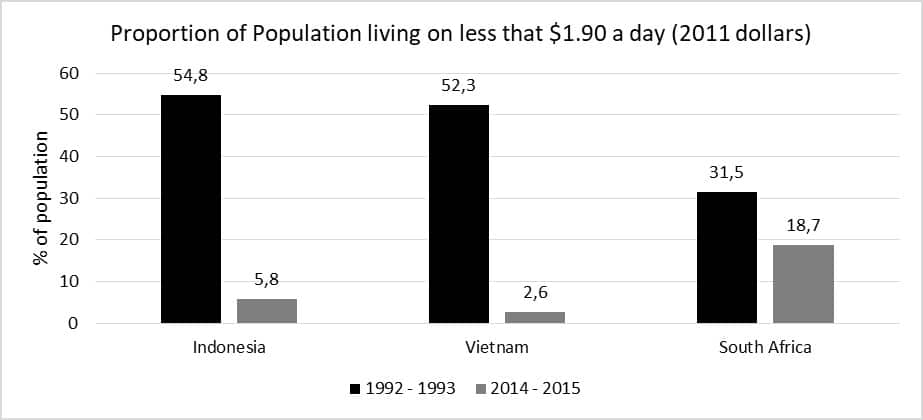

This point is well made. Figures from the World Bank’s database demonstrate the extent of progress in reducing poverty – here defined in terms of those living below $1.90 a day (in 2011 dollars, at purchasing power parity) – in Indonesia, Vietnam, and South Africa. Because the data is not provided for each year and is not consistently available for each country, the chart below shows a broad comparison between the early 1990s and the mid-2010s.

The difference is stark; and this is also the case in respect of poverty as defined by national measures – which are calculated differently from those represented in the chart. Although the data is far from complete, the latest figures in the World Bank’s database for Indonesia put the proportion of those living in poverty at some 9.8% and for Vietnam at 6.7%. The equivalent figure for South Africa is 55.5%.

From a bird’s eye perspective, this can be explained by the differential economic performance of the various countries. This is a complex matter, but a few basic trends help to illuminate it.

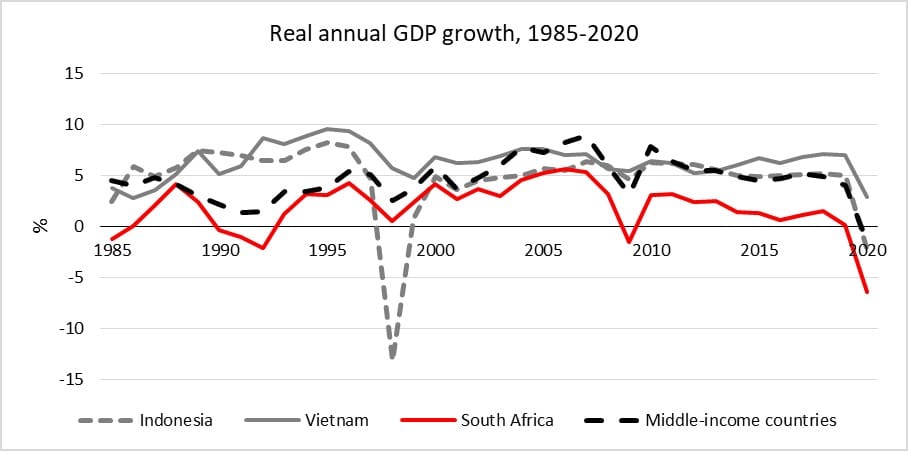

The first is economic growth. The chart below shows real GDP growth for each of these three countries, as well as the aggregate performance of middle-income countries (all three of these are so classified) since 1985.

As is apparent, each country has gone through cycles of growth and contraction, some associated with domestic drivers, other with the global economy. The steep slump in South Africa’s performance in the early 1990s and recovery as the decade went on is testimony to the political stabilisation of the transition. The Asian financial crisis registers on all countries (with a particularly hard impact on Indonesia), as does the global financial crisis. However, Vietnam managed growth rates in excess of 7% over time, with Indonesia achieving around 5%.

The key takeaway, however, is that South Africa has lagged behind its peer countries since the 1980s. Post the global financial crisis – and into the Zuma and Ramaphosa presidencies – it has managed only about half the rate of growth of the middle-income group as a whole, and significantly less than Vietnam and Indonesia.

In 2012, the NDP envisaged growth of some 5.4% per annum, but Stats SA reported growth of 4.9% for 2021 (making it the highest growth year since 2007). However, this represented a recovery off a low base after the sharp pandemic- and lockdown-induced devastation of 2020, when the economy shrank by -6.4%.

Between 2010 and 2019, the economy grew by just 1.7% per year. In February 2022, the Treasury projected a paltry 2.1% for the current year (likely to be revised downwards), and an even more dismal average of 1.8% over the coming three years – a mere third of the growth rate aspired to in the NDP.

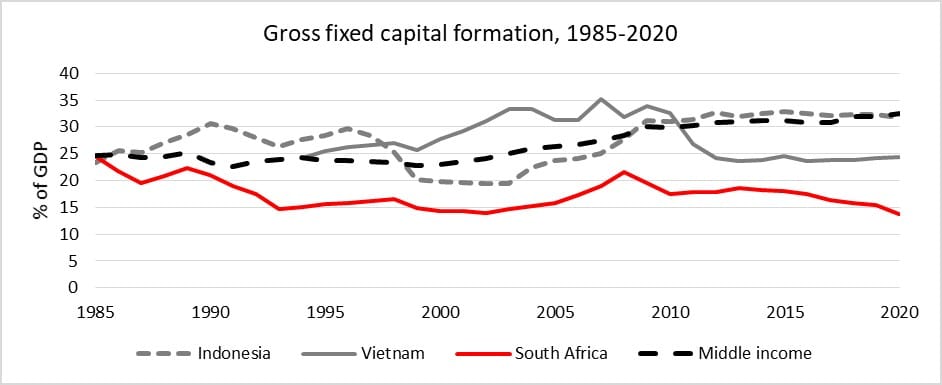

An obvious driver of growth is investment. The chart below shows this (gross fixed capital formation) as a percentage of GDP.

Interestingly, all three of the countries, as well as the middle-income group as a whole, began this period with annual investment rates in the region of around 25%.

But while investment in Vietnam, Indonesia, and the aggregate rose (allowing for some variation, and a fall-off in Vietnam over the past decade), in South Africa, investment initially declined, then went flat, rising somewhat in the late 2000s during the commodities boom and in the run-up to the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and then falling again.

With an investment rate of below 14% of GDP in 2020, it is significantly below the rate in Vietnam (at over 24% of GDP), and less than half of that in Indonesia and the middle-income group. The National Development Plan had looked towards South Africa achieving a level of 30%.

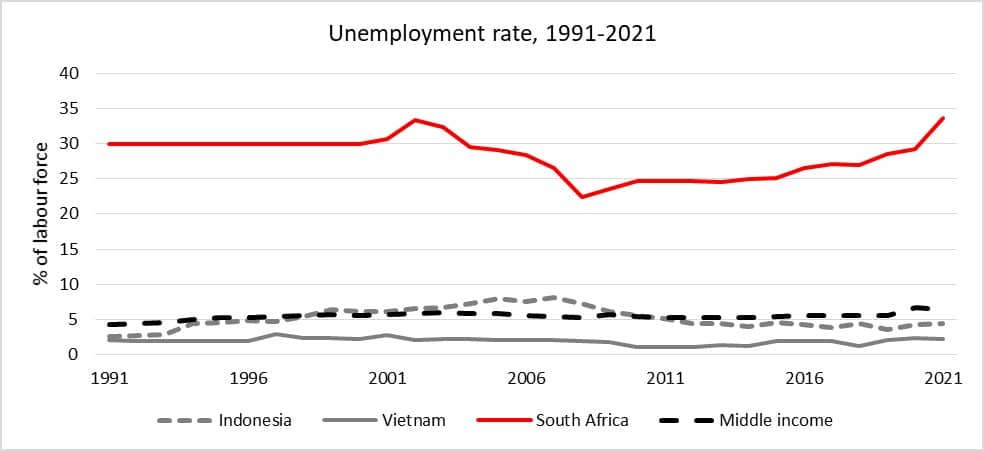

The prime manifestation of all of this, and intimately bound to poverty (perhaps more directly, a brake on individual and household mobility) is unemployment. The chart below shows how South Africa compares to Indonesia, Vietnam and the middle-income group.

In this area, South Africa has a particularly serious problem, and diverges widely from its peers. Its 2021 rate (it is now somewhat higher) stood at over 33%. Middle-income countries typically have an unemployment rate of around 5% or 6%. In Vietnam, it sits just above 2%, and in Indonesia, in excess of 4%.

The lessons seem clear. South Africa needs to attract investment to elevate growth, which would generate employment, and which in turn will help reduce poverty. This is a very simplified rendering – it is not disputed that any number of other factors would play a role – but it is a necessary conjunction of factors. It is also uncontentious as a broad approach.

In contrast, how to achieve this has been contentious – and by the evidence of the state of the country, whatever South Africa has done has proved largely ineffective. So, to follow the National Planning Commission, what lessons can South Africa draw from the successes of Indonesia and Vietnam?

Next week’s column will explore this question.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend